Her name is not widely known outside broadcasting circles, where she was bestowed with the moniker the “First Lady of Television”.

And the chances are that you could ask 100 people in the Highlands if they had ever heard of Grace Wyndham Goldie and be met with blank stares.

Yet this trailblazing figure, born in Arisaig in 1900, was one of the most forward-thinking and inspirational people in the history of TV.

She transcended all the obstacles she faced to create programmes such as Panorama, That Was The Week That Was and Tonight and nurture the talents of a string of ‘Goldie Boys’ including Alasdair Milne, Huw Wheldon, Cliff Michelmore, Richard Dimbleby and a young chap called David Attenborough.

The latter has never forgotten her encouragement and described the daughter of a Scottish engineer who worked on the Mallaig railway and the Aswan Dam as “one of the most influential of television’s pioneers”.

She realised the potential of TV

If you’ve ever seen Singin’ in the Rain, you’ll have an idea of the hurdles Grace faced when she moved from being a weekly columnist with The Listener magazine into the emerging bureaucracy of the BBC.

For most of the executives, clad in dicky bows and dinner jackets, their only interest was in radio and they sneered at the notion that television would become a hugely important medium.

In was the same “flash in the pan” as the talking pictures which were initially derided by many Hollywood studios.

In fact, Grace later gave an interview with Dennis Potter – of The Singing Detective fame – where she revealed the entrenched attitudes she faced while working in a rat-infested basement building at Broadcasting House.

‘Don’t worry yourself about it’

She said: “Do you know, there was this radio executive before the war who pooh-poohed some remark I made about the new toy called television.

“He said: ‘My dear girl (Grace was in her 30s at the time), television will be of no importance in YOUR lifetime.”

But she was right and they were wrong and her enthusiasm was obvious when she watched a broadcast revue called Here’s Looking at You at Alexandra Palace in London in 1936.

She concluded the production “was terrible, the whole thing was terrible, the reception was awful… and I was convinced that this was going to become one of the most influential things that had ever been created”.

Grace gradually climbed up the ladder

In 1944 a letter was sent to her old address, which was eventually redirected to her new residence.

She recalled: “It asked if I would like to apply for a job as a radio producer? Well, yes, I would.

“I went on to become a senior producer in the next four years and then, in 1948, I was asked to move across to Alexandra Palace where the BBC had resumed its TV service.

“It was incredibly hard work at the time – we had to do everything for ourselves and nothing we wanted ever seemed available.

“But I never regretted the move. There was so much to be done.”

‘Television was a bomb about to burst’

So very, very much, but Grace was up to it. She started the programme Press Conference, which featured politicians being grilled live for the first time.

She was in charge of the inaugural TV coverage of the 1950 general election results programme on February 23 1950, when she insisted there should be no bias, no partisanship, just the facts presented in a manner viewers could understand with the help of analysts and reports from constituencies.

And that meant everywhere, not just the metropolitan London circles in which so many politicians of her era habitually dwelled.

People were waiting for her to fail

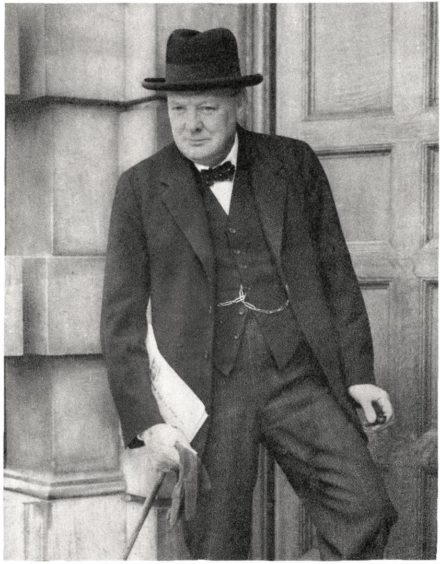

It was a fraught assignment because both the incumbent Labour government (whose majority was drastically reduced at the polls) and the Conservative opposition (led by Winston Churchill, who loathed the BBC) were watching from the sidelines, waiting to pounce on any fluffs, blunders or partiality.

There weren’t any. In one night the future of TV had changed forever, orchestrated by a woman who described television as “a bomb about to burst”.

By 1955 the impact of television on election nights had proved seismic.

It prompted returning officers to hold their counts immediately after the close of polls, so that the results were declared during the early hours of the morning, rather than be delayed until the following day.

In 1955, for the first time, a majority of results was confirmed on the night (357 of the 630 constituencies).

And Grace, again, was at the helm.

She believed TV was a force for good

That initial election production was, for Grace, a watershed moment; one that opened her eyes to the infinite possibilities of the box in the corner.

At the time, hardly anybody except the rich owned televisions but, during the next decade, they started appearing in millions of living rooms across Britain – and the Scot was determined to make the medium an equalising force.

She later said, remembering her roots: “No one, not even a (Harold) Macmillan, or a (Clement) Attlee, a (Hugh) Gaitskell, or an (Alec) Douglas-Home, a (Harold) Wilson, an (Edward) Heath or a (Margaret) Thatcher, whose future and that of their parties depended upon the result, knew what it would be earlier than a shepherd in the Highlands or a housewife in Islington.

“The privilege of the few had been extended to the many”.

Grace was ‘more eagle than wren’

None of this happened by accident, nor did Grace suffer fools gladly.

A driven individual in a world where so many connections were formed through the ‘old boy’ or ‘old school tie’ nexus, Attenborough described her as “more eagle than wren”, but she recognised she was an outsider and was conscious that she had to be better than her male counterparts to gain parity with them.

Dennis Potter was clearly impressed and wrote in the early 1960s: “Grace told me that she had never deliberately set out to follow a career – ‘I’ve simply followed the paths which have opened up for me’.

“These have taken Mrs Wyndham Goldie – as the head of TV Talks Group – to the ‘Cabinet of All the Talents’ now in the cockpit of the new-look BBC.

“She has nourished the growth of Panorama, Tonight, Monitor and the rest. And she has trained the young men who are now shaping the BBC’s future.”

Her impact on them was unforgettable

Her acolytes held a high opinion of Grace; others described her as “uncompromising”, “difficult”, “capricious” or even a “woman of iron whim”.

But one of her proteges, Melvyn Bragg, recalled her as a force of nature who had to be tough to battle the red tape which pervaded the corporation.

He told The Guardian: “She was very clever, completely charismatic and would perch on a stool in the bar and hold court, and toughies like Milne and Tony Jay (who later co-wrote Yes Minister) and even Attenborough and all the rest of them would just wait our turn to talk to Grace Wyndham Goldie.

“She knew what she wanted. She had a very good eye for young people who were talented; and she had a very good eye for what would make a programme. Grace was quite somebody.”

She could have been first female DG

After her retirement in 1965, Grace wrote a memoir, Facing the Nation, that amply demonstrated her love for television and its importance in entertaining people and bringing them together, but also informing them about famine, starving children and the victims of war, earthquakes and genocide.

She added: “Small wonder that millions of British viewers, troubled and made to feel guilty by what they see on television, took refuge in 1976, and were among the 250 million people in 83 countries who watched the amiable imbecilities of A Song for Europe (now the Eurovision Song Contest).

But could she have become the corporation’s first Director-General?

Panorama journalist Woodrow Wyatt backed this move in 1985 (just a year before Grace’s death), but she was probably too much her own person.

Iron will would have met Iron Lady

As he said: “No one was allowed to slant, right, left, or liberal, in any of the programmes she controlled.

“She could have run the BBC far better than any of (Lord John) Reith’s successors, and would have left a modern ethos behind her. But the prejudice against women was, and is, nearly insurmountable.”

Grace lived with that all through her life, but prospered and made a difference.

She deserves to be better known in her homeland.