They could wield 7lb axes, six-foot cross-cut saws and fell 10 tonne trees- but chopping down patronising male attitudes was much more of a challenge for the lumberjills of World War Two.

Exactly 80 years ago (April 18 1942), the Women’s Timber Corps was established as a branch of the Woman’s Land Army.

There was a desperate need for timber to feed the war machine.

Britain needed to produce millions of tonnes of wood for pit props, railway sleepers, telegraph poles, gun butts, ships and aircraft, as well as packaging boxes for bombs and army supplies.

The government at first refused to employ ‘the fairer sex’, deeming them unable to cope with the tough work.

Instead they tried to employ male British prisoners, male dockyard workers, male students and even school boys.

But the Forestry Commission had been employing around 1,200 women to solve a labour shortage since 1940, known as the Women’s Timber Service.

When the Ministry of Supply took on the Forestry Commission’s responsibilities in 1942, the women were absorbed into the Women’s Land Army, becoming the Women’s Timber Corps (WTC), amid much male scepticism.

And forward they came to join the WTC, 18,000 women aged 17 to 24, leaving behind work as clerks and typists, hairdressers, nurses and teachers.

Lumberjills rivalled men in strength and skill

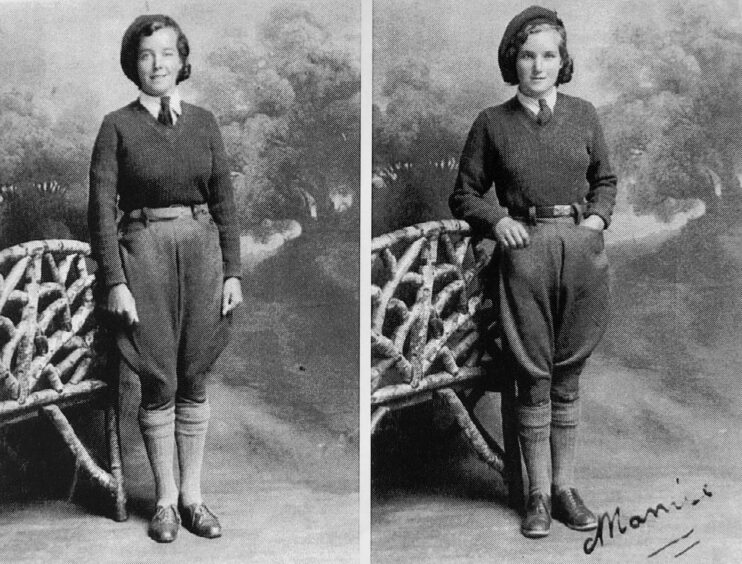

Leaving their homes for the first time too, as they headed to WTC training camps in England, and to Sandford Lodge near Brechin, Angus and Park House, Drumoak, Aberdeenshire to train in felling, haulage, sawmilling and measuring timber.

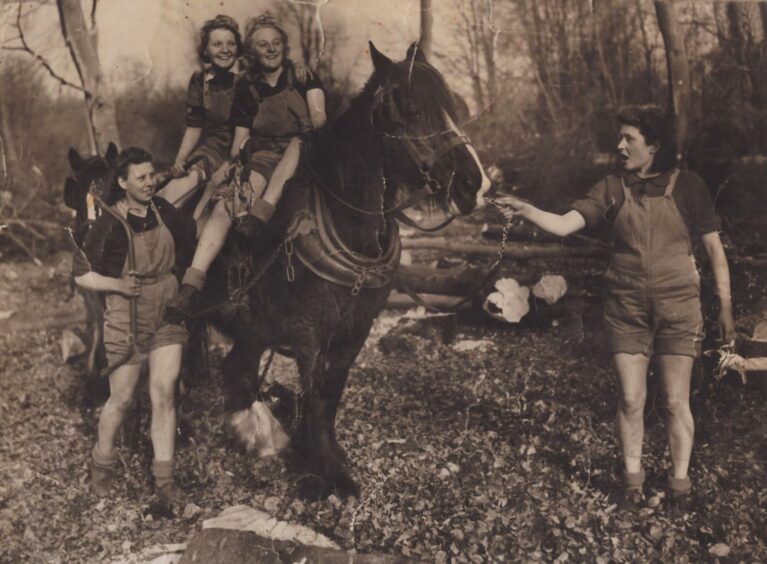

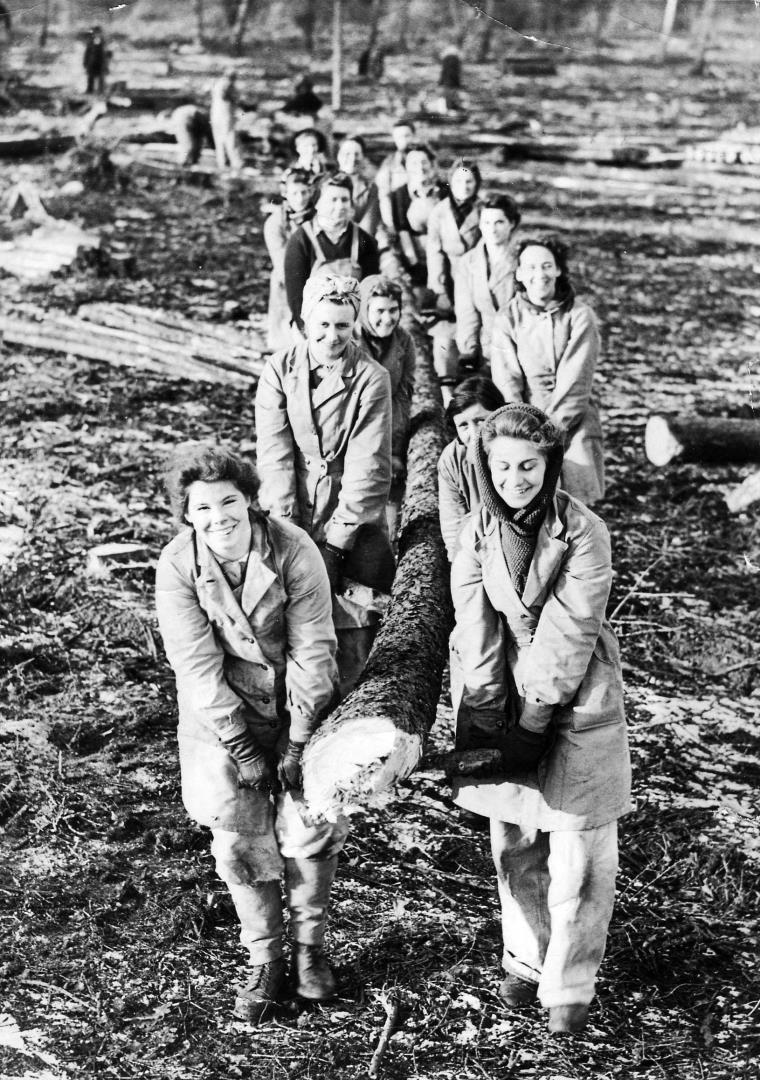

Many women rivalled the men in their strength and skill, working by hand, without the benefits of modern power tools and machinery.

One Scottish lumberjill, Bella Nolan, challenged her foreman to a felling duel when he said he didn’t think much of the women.

Each took one end of the cross-cut saw and together they felled 120 trees in a day.

Author Joanna Foat spent two years interviewing dozens of these remarkable women, immortalising them in her book, Lumberjills: Britain’s Forgotten Army (History Press, 2019)

She said: “I was shocked to discover how the women were treated at the beginning of the war.

“They were laughed at for their enthusiasm to offer their services, regarded as ornamental rather than useful and many timber merchants did not want women taking over the jobs of skilled men.

“In fact, the lumberjills not only pioneered a new fashion for women in trousers, wearing jodphurs, but they also proved that women could carry logs like weight-lifters, work in dangerous sawmills, drive huge timber trucks and calculate timber production figures on which the government depended during wartime.

“Out in the forests away from the restrictions imposed on women by society, they realised they could sit astride a tree, smoke a pipe and fell massive trees just like the men, if they wanted to.”

A cut-glass male voice in this Pathe newsreel pronounces: “Felling trees may harden the muscles, but see what it does to the dimples… There’s a knack and a skill in swinging an axe, especially for a girl who’s never swung anything heavier than a handbag.”

Enough to make any woman want to plank an axe in his head.

Despite women’s proven abilities, male attitudes refused to change.

At the end of the war the Women’s Timber Corps received no recognition, grants or gratuities and the director of the Women’s Land Army, Lady Gertrude Denman resigned in protest.

They were not allowed to keep their uniforms or attend Remembrance Day parades, because they were not part of the fighting forces.

The women went back into traditional roles of clerical and shop work, teaching, domestic service or got married.

More than 60 years later, when most of the women were in their 80’s, the prime minister, then Gordon Brown, finally presented them with a badge.

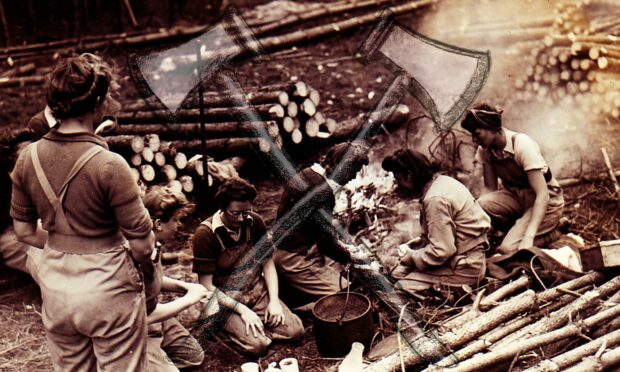

But to their disappointment the badge bore a wheatsheaf, the emblem of the Women’s Land Army, not a pine tree or a pair of crossed axes.

In 2000, it was agreed that some surviving members could attend the Remembrance parade in London.

Joanna added: ‘Many of the lumberjills I met were still upset that they remained a footnote in history, so I wanted to make sure they were remembered.

“Their incredible feats of physical and mental endurance inspire women today, especially female forestry workers and arborists from across the world.”

Or as Pathe would have it: “Some girls are jolly good fellers.”

One of the lumberjills was Anne Shortreed who graduated from art school before the war, and then became a Women’s Timber Corps trainer at Park House in Aberdeenshire.

She then went to the Anna Freud Institute in London, a charity which pioneered mental health care for children and families facing emotional upheaval in wartime Europe.

In 1945 she went with the founding members of the British Embassy to Czechoslovakia, assisting with the resettlement of British women married to men of the former free Czechoslovakia.

She won a British Council Scholarship to Prague College of Applied Arts in 1946 and graduated with a degree in 1951.

Professional artist

She then became a professional artist and illustrator in Czechoslovakia before returning to Scotland to teach art in West Lothian secondary schools until she retired.

Joanna herself first discovered the story of the lumberjills while working for Forestry England in 2010.

Her father had given her an axe for Christmas one year because she loved chopping wood.

Inspired by the story of the Women’s Timber Corps, Joanna travelled the country to interview sixty of the surviving women on her quest to uncover their wartime stories.

You might enjoy:

The Women’s Land Army had a strong presence in Ballater

Women’s Land Army played a vital part in the Second World War