“Get out the way! You don’t pay road tax!” is a common shot fired across the bow of cyclists by irate motorists who see them as an obstacle rather than a fellow road user. But is it true?

In a word, no. In fact, road tax – meaning a tax on cars which is exclusively ringfenced for putting back into the roads – hasn’t existed for more than 80 years.

Try as you might, you won’t find any reference to ‘road tax’ on the UK Government website, nor on the website of motoring organisations. ‘Vehicle tax’, ‘car tax’, ‘Vehicle Excise Duty’ (its official name), certainly. But ‘road tax’? Not a chance.

The reason for this is straightforward: the tax you pay on your car doesn’t go directly towards funding the roads. Like all other taxes, it is paid into the government’s coffers to be spent across all public services – from defence to the NHS.

Vehicle tax isn’t a tax to fund the roads either – rather, it is based on the emissions that your vehicle adds to the environment. That’s why an electric vehicle pays no car tax at all, and big burly SUVs with hulking diesel engines pay the most.

These facts aren’t lost on the scores of cyclists who completed the Press and Journal’s Pandemic Pedal Power survey which asked, among other questions, whether cyclists should pay for a road licence for their vehicles in the same way as a car. They answered “no” overwhelmingly.

But “road tax” hasn’t always been a misnomer – and the first cars on UK roads were indeed taxed to pay for the roads that they ran on. The problem was that supply couldn’t keep up with demand.

Four-wheeled vehicles have been taxed by the government since the late 19th century, when the first motorised vehicles began to appear on what were then regarded as common paths.

However, the light locomotives, as they were known at the time, were rapidly associated with what was often called the “dust nuisance”. Motorists gadding about would spray pedestrians and buildings in dust whipped up from the dirt roads.

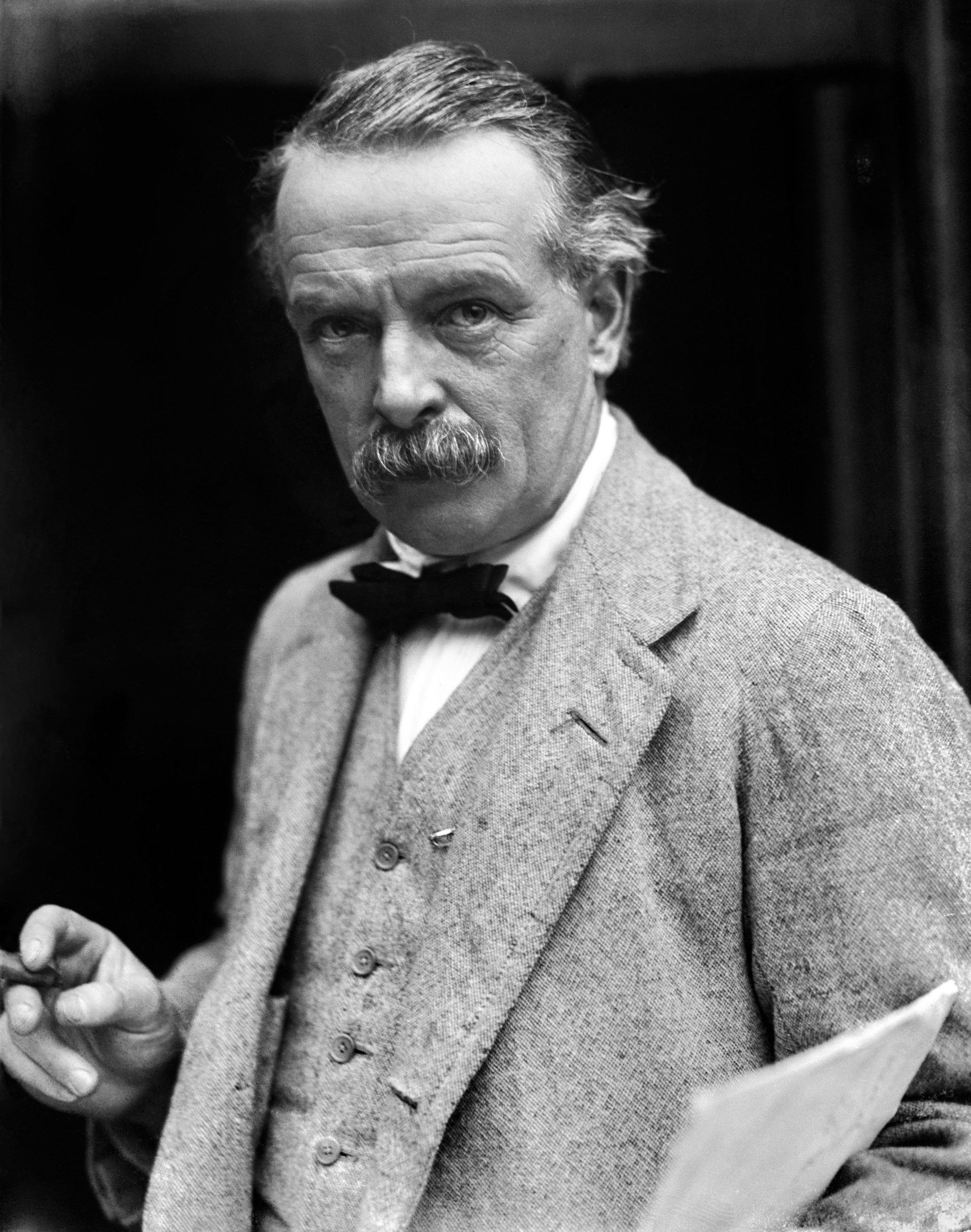

This led to a Royal Commission on Motor Cars which proposed a central road fund directly topped up by car owners. Then-chancellor David Lloyd George, later to become prime minister, incorporated the Road Fund into his 1909 budget.

A centrally administered Road Fund would, he said, right the wrongs of drivers he said “have not been given the opportunity of contributing to the upkeep of the roads they help so effectively to tear up”.

Ironically, much of the Road Fund’s money was used on projects other than the roads, as the governments of the day raided it when cash was short elsewhere. As chancellor, Neville Chamberlain abolished the hypothecation – ringfencing – of vehicle duty in 1936.

Even back then, politicians feared that ringfencing car tax was brewing an unhealthy entitlement among motorists of the day.

Sir Derrick Gunston, MP for Thornbury, told the House of Commons during a budget debate at the time: “I think many motorists do believe that because they pay taxation on their motor cars they are entitled to say how the money should be spent.

“That, of course, is contrary to our democratic principles in the raising of finance and I, personally, am delighted that the Chancellor of the Exchequer has, once and for all, removed this anomaly from our system.”

Since 1937, all road repairs have been funded from general taxation – and the roads haven’t had their own national funding body since 1955. So why has the inaccurate “road tax” monicker stuck?

Likely, “road tax” has stuck as a name for VED in the same way that “Hoover” has for vacuum cleaners – it’s easy to say, and it’s the done thing, but it isn’t necessarily right.

“There’s a lot of people who don’t know that car tax doesn’t pay for the roads,” says Aberdeen cycling novice John Prince. “You never notice it because you’ve just always called it road tax.”

Mike Ward MBE, curator of the Grampian Transport Museum, describes the phrase as a “leftover from decades ago”, adding: “Vehicle Excise Duty is really a tax on various taxation classes for road vehicles. Weight, green credentials, size, age, etc are taken into account.”

In addition, research by Cycling UK suggests that more than four-fifths of cyclists also hold a driving licence – and if they drive, the chances are they own a car, and pay tax on it.

To settle a debate, then: cyclists pay as much “road tax” as any car driver. Which is to say, of course, that they don’t pay any road tax at all.