It is one of the most insidious trends in modern rugby: the sight of coaches withdrawing three or four players after 60 minutes and sending on high-powered replacements with the aim of capitalising on tiring opponents.

The current regulations, which allow teams to make eight changes during a match, have effectively transformed the sport to 23-a-side and there have been plenty of occasions in the last decade where international line-ups have introduced impact performers who have subsequently been involved in injuring rivals.

Radical changes in rugby

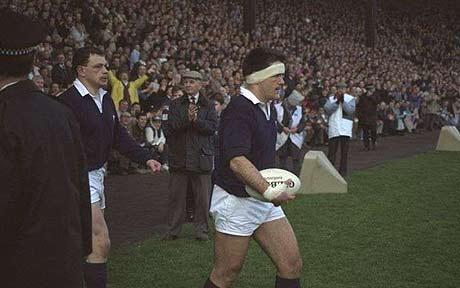

That’s hardly surprising, given how the game has radically advanced from where it was in the days before professionalism. I recently watched the 1990 Grand Slam showdown between Scotland and England at Murrayfield and one of the most obvious features of that (still riveting) contest was the diminutive stature of many of the combatants.

Yes, they had lashings of pride and passion and no shortage of talent or technique, but this was still in the amateur era and replacements could only be made in the event of injury. That benefited the hosts who lost Derek White early on as Hawick’s Derek Turnbull entered the fray and he and his colleagues produced a barnstorming performance even as the crowd grew increasingly vociferous in their support.

David Sole’s triumphant team were coached by Jim Telfer and Ian McGeechan, whose names are part of the fabric of rugby history and, whether or not you agree with their opinions, they have done more than enough to command respect from their peers.

Fears expressed over impact players

That explains why it is long overdue to halt the development of impact players and why the issue has been raised by McGeechan and a group of the greatest names in the pantheon, including Willie John McBride who captained the British and Irish Lions “Invincibles” in South Africa in 1974, Gareth Edwards, Barry John and John Taylor.

This illustrious quintet have written to Bill Beaumont, the chairman of World Rugby, urging the global governing body to reduce the number of available replacements from eight to four, arguing that if the issue isn’t addressed as a matter of urgency that somebody will be killed on a rugby pitch in the future.

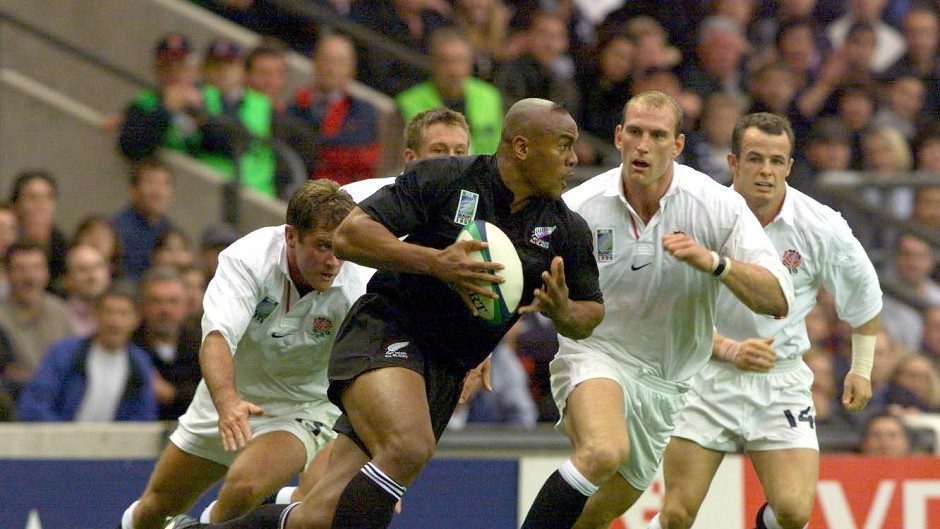

This might sound dramatic, but there have been sufficient sickening injuries in the sport recently to underline how much it has changed with some players becoming more like battering-ram behemoths than potential tacklers or try-scorers.

Their letter isn’t sensationalistic. Far from it. As you might expect, given McGeechan’s reputation as one of the most cerebral thinkers in his domain, it is forensic, hard to dismiss, and points out the genuine pitfalls of sticking with the status quo.

As it says: “More than half a team can be changed and some players are not expected to last 80 minutes, so they train accordingly, prioritising power over aerobic capacity.

“This shapes the entire game, leading to more collisions and, in the latter stages, numerous fresh ‘giants’ crashing into tiring opponents.”

Rugby will never be risk-free

Rugby is already dealing with a rising number of cases of former internationalists being diagnosed with early onset dementia and England World Cup star, Steve Thompson, is part of a landmark legal action against World Rugby to make the game safer.

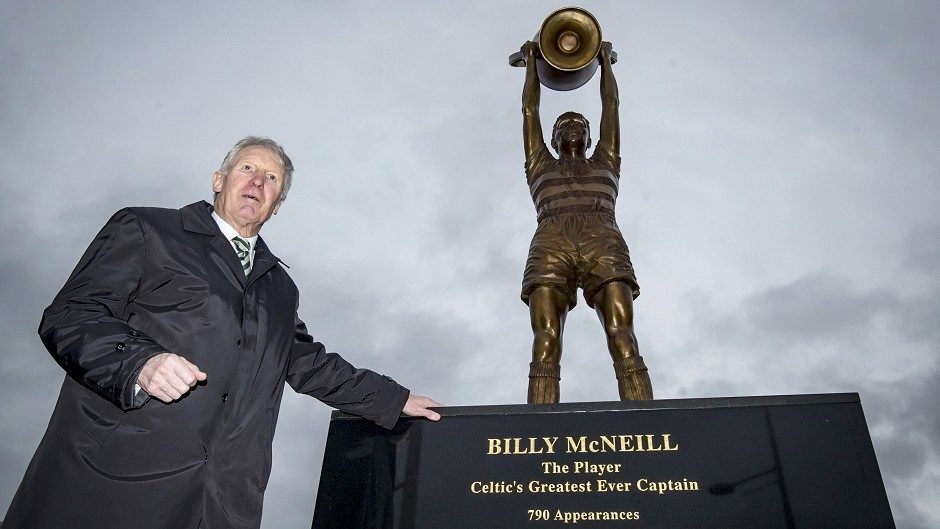

They are not looking for the sport to become risk-free – which is impossible, considering the fast, furious and frenetic nature of life in and around the breakdown – but, just as in football, where many former luminaries, including Billy McNeill, Frank Kopel, Jack Charlton, Nobby Stiles and Gerd Muller, have succumbed to Alzheimers or dementia, there are steps which can be implemented to make things safer.

World Rugby has insisted it is carrying out detailed research into the issue and a comprehensive review of the impact of substitutes in the elite game is being undertaken across more than 2,000 matches by Bath University “to examine whether more injuries happen later in fixtures, whether starters or substitutes are more likely to be injured, the positions with the most exposure and the nature of injuries.”

But, while these intentions are doubtless well-meant, they don’t acknowledge the central problem. Namely, why on earth has rugby allowed the use of so many replacements in the first place? Even if you accept there needs to be front row and back row cover, there’s no need for teams to be allowed any more than five substitutes.

The current rules are a mess

Granted, there’s nothing amiss with coaches naming seven or eight players to sit on the bench, but on the understanding that they can only make a fixed number of changes, except in the case of injury. This routinely happens in football, so why not rugby?

I have never forgotten France bringing on an entirely new front five in the closing stages of a Six Nations Championship match. It was a ridiculous situation, but there was nothing to prevent it occurring. The regulations, as they stand, are a mess.

It was the Welsh stalwart Sam Warburton who voiced his fear that a player might die on the pitch unless the legislators shrugged off their inertia and, however belatedly, accepted their responsibilities.

As McGeechan and his confreres have concluded in their timely missive: “Let’s have no more empty words, we call upon Sir Bill [Beaumont] to act now in the profound hope that Sam’s words do not become prophetic.”