It was one of the few occasions where the opening ceremony of the Olympics transcended everything else which followed at the Games, but Muhammad Ali’s slow walk with the torch in Atlanta 25 years ago was mesmerising.

A quick-witted interviewer’s dream with an endless stream of banter, opinions and anecdotes at the peak of his career, it seemed dreadfully cruel that Ali should be forced to battle with Parkinson’s syndrome, a gruelling fight which he couldn’t win and which deprived him of his fertile powers of oratory and wit.

But, even here, his sheer totemic presence, power and indomitability sent out an inspirational message as he took centre stage at the Games in Georgia.

There was a gasp from some sections of the audience when he first emerged, his hands shaking as he moved forward in lumbering fashion to light the flame, but there was something else: a tangible determination on his face to ignite the Games spirit even to the extent where he was physically burned by the torch in the process.

I can still remember the tears welling up in my eyes as I watched this once-wonderfully lithe and athletic man struggle to walk towards the podium. It was as if time had stopped and millions of us were silently willing him on.

But eventually, he managed it, and you could detect him letting us know that, no matter his troubles, no matter his travails, he was still the king of the world, all those years on from his heavyweight achievements.

It was the high point of the whole Olympics; nothing could match his stamp of greatness. As one American journalist said simply: “How do you follow that?”

But there again, was there ever a more compelling force of nature than the late ringmaster? Here was a man of infinite grace, unquenchable pride, a fellow who transcended race or religion even as he addressed pivotal questions in both realms.

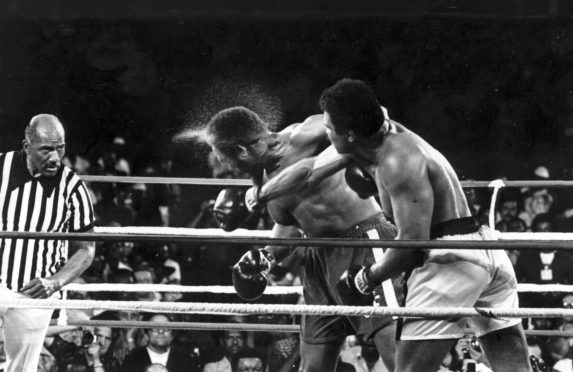

For those of us of a certain age, he wasn’t merely The Greatest because of what he achieved in his boxing career, which started in golden fashion at the 1960 Olympics. Indeed, strange as it may seem, those of us who weren’t aficionados of the fistic arts were doubly captivated by the Louisville Lip’s ability to rise above the sport and the often grubby activities which surrounded his epochal victory against Sonny Liston in 1964 and the fabled Rumble in the Jungle a decade later.

First and foremost, Ali possessed effortless charisma and personality to burn. Whenever he appeared on Michael Parkinson’s eponymous chat show in the 1960s and 1970s, he always held his audience in the palm of his hand with a beguiling mixture of wit, evangelical zeal and compulsion to tell the truth as he perceived it.

He was sport without any of the spin or PR nonsense. Nowadays, he would be taken aside by corporate lackeys and subjected to what are euphemistically described as “media communication courses” in a bid to transform him into a jargon-spouting automaton. Much good it would have done them in Ali’s case.

But, 50 years ago, it was still possible to parade your passions in public, especially if you were as articulate and courageous as this character. How many famous sporting luminaries were prepared to go to prison rather than fight in a war – in Vietnam – which he considered to be an obscenity? How many were ready to embrace another religion and proclaim their commitment to Islam in such a public fashion?

In the ring, Ali, of course, was a genuine nonpareil, mixing one-liners with punches and manoeuvres which inflicted torment and bewitched, bothered and bewildered so many opponents. He excelled at the Games in Rome and emerged as a lustrous presence during JFK’s ephemeral New Frontier.

But those of us who witnessed him at his peak weren’t simply impressed by his elegance and Astaire-style rhythm even as he pummelled rivals.

Instead, we marvelled at how sublimely he tapped into the psyche of youth in the 1960s. He was a rebel WITH a cause: somebody who spoke up for civil rights, yet not just in the United States, but the whole world.

It would have been easier for his family and friends if he had simply indulged in playful performances with Parky, but the evening where he reduced the Yorkshireman and his audience to impotent silence while launching into a tirade defending his race and his Islamic faith was as awe-inspiring as it was awkward for his host.

When the Olympics start in Tokyo on Friday, there will be nobody to carry the torch in such spectacular fashion as Ali or the diminutive but wonderfully gifted athlete Cathy Freeman who followed in his footsteps in Sydney four years later.

I was in the packed Sydney arena when the indigenous Australian became the focus of global attention and appeared on a plethora of newspaper front pages in 2000. These are the sort of moments which make the Olympics the greatest show on earth.

Sadly, the stands will be empty in 2021 and the silence will be deafening. Let’s just hope that this cursed Covid doesn’t further diminish the schedule in the coming weeks.