A Ross-shire veteran of the World War Two Russian Arctic convoys waited until his deathbed to dictate his memories of that time.

Now his younger brother wants the world to know about the gruelling hell he and many other merchant seamen lived through.

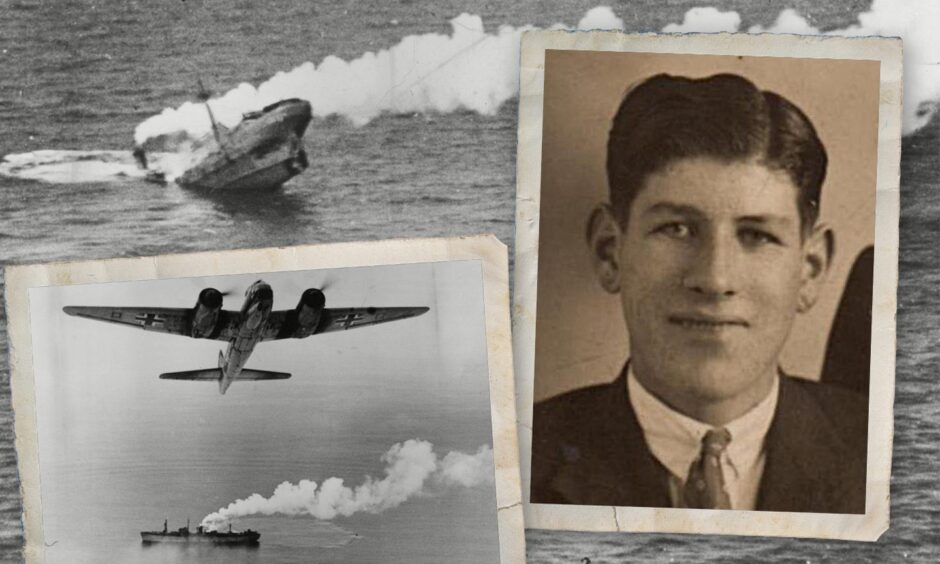

Donald Grant, born in the village of Mellon Charles, Aultbea served in the notorious PQ17 convoy as a seaman in the Merchant Navy, sailing from close to home in Loch Ewe to Murmansk.

Ships could sink under weight of ice

The waters were so cold that the ship could become top-heavy with ice and sink if the men didn’t chip it away, 24/7.

If a man fell overboard he would only be rescued in the first two minutes.

Any longer, and he would never recover even if brought aboard alive, so he was left in the water.

They were constantly under threat from Nazi bombs and torpedoes.

Donald preferred not to talk about it after the war

For decades Donald kept quiet about his ordeal.

But on his deathbed, he decided to talk, dictating his memories to his son David, now in Australia.

The document remained in the computer of Donald’s younger brother, also christened Donald but known as Danny, for almost a decade.

Rather than letting it lie there and be lost to posterity, Danny has decided to share it with the P&J.

War memories were often so traumatic to the servicemen and women who endured them that they couldn’t bring themselves to talk about it afterwards.

“It is hard for this present generation to realise what experiences these young people were exposed to during the war years,” Danny, 93, said from his home in Aultbea.

“Donald thought it was important that they and succeeding generations know about it.”

Donald was ten years older than Danny, born in 1920 to Hector and Mary Grant in Mellon Charles, later moving to Mellon Udrigle, six miles north of Aultbea.

He left home at the outset of World War Two and joined the Merchant Navy.

Despite being torpedoed on at least two occasions, he survived.

Danny said: “He did mention a particularly poignant moment when sailing from Loch Ewe bound for Murmansk in northern Russia.

“As they were sailing through the Minch, he detected smoke from his parents’ chimney.

“They were unaware of his whereabouts. As far as they knew he could have been anywhere in the world.”

Cold, hungry and sleep-deprived, Donald, then aged 22, remembered one particularly gruesome incident.

They had picked up so many survivors of Nazi bombs and torpedoes that the space to put them all was becoming critical.

Because of the extreme weather and icy waters, many of these picked up were already dead or dying.

The medical staff certified the dead and they were immediately prepared for burial at sea by being sown into canvas with a weight added to help them to sink.

Stitching up the dead

Donald was roped in to help stitching up those who had been declared dead by an over-worked doctor.

Part of the job was to pass a sail needle through the man’s nose, a sort of second opinion that death had actually occurred.

On one occasion he was passing the needle through when the man sat up and angrily asked Donald what on earth he thought he was doing.

“This incident must have ranked fairly high amongst all the traumas that these sailors were experiencing,” says Danny, 93, who returned to live in Aultbea after a career as a detective in the Glasgow police.

But the incident which most hurt Donald came not in the hell of the North Atlantic, but when he was on leave at home.

Danny said: “After several voyages to Russia, he and another seaman were sent on leave on the advice of the ship’s medical team.

“They must have sensed that they had seen enough.

“They were waiting for a train at Euston station when some women approached them and handed them white feathers, because out of uniform, they looked like civilians.

“No doubt these women were unaware of the horrors that these two ‘civilians’ had so very recently experienced.”

A haunting hurt

Danny reckons the pain of this incident haunted Donald to his dying day.

“It happened again in Inverness,” he said. “He was waylaid at the station and branded a coward for not being in uniform. In fact the group saw his MN (Merchant Navy) badge and identified Donald and his friend as maternity nurses!”

Donald served for a while on a requisitioned Egyptian ferry, Zamalek.

Zamalek’s bravery in PQ17

Danny has found an account of the Zamalek’s bravery in convoy PQ17.

He said: “During the night of 9/10th July somewhere in the White Sea, forty Junker 88s carried out an attack that lasted over four hours, during which the ships Hoosier and El Capitan were damaged and had to be abandoned.

“Their crews were picked up by the ships Poppy and Lord Austin as the Zamalek had over 240 survivors on board and could not accommodate any more.

Luftwaffe’s main target

“Zamalek then became the Luftwaffe’s main target and was at one stage completely hidden by the splashes of exploding bombs.

“One stick of bombs took the Zamalek right out of the water, to such an extent that daylight could be seen between the keel and the water.

“She sustained shock damage to her engine and had to stop for repairs to be made.

“Fortunately, with so many survivors on board there was no shortage of experienced engineers to help.

Given up for lost

“She was given up for lost by the other ships in the convoy, and when she re-joined she was loudly cheered by her consorts.

“Some weeks later as she was undergoing repairs in a shipyard on the Clyde, and the Daily Record showed a photograph of the Zamalek, headed ‘The little ship that sailed through hell’.”

Donald and two other young men from Aultbea, twin brothers Colin and Frank Crichton were part of the crew that sailed the Zamalek back to Alexandria within a few weeks of the war ending.

There she was handed back to the Egyptians, from whom she had been borrowed at the outbreak of war.

Donald was lucky to survive PQ17 and went on to live to the aged of 95, dying in 2015.

Lots of Allied ships and personnel lost in PQ17

Two-thirds of the British and American merchant ships in PQ17, 24 out of 35, were sent to the bottom by German U-boats and planes.

More than 150 Allied seamen died in flaming ships or in the lifeboats scattered around the merciless icy waters.

But the work of the convoys were essential to keeping Russia on-side during the war.

Staggering value of goods conveyed

The value of the war materials sent by convoy from Britain during the war was £308m, more than £18bn in today’s money.

The value of the raw materials sent, including medical supplies, hospital equipment, food and industrial goods amounted to £120m, more than £7bn today.

More like this:

Bertie visits Lewis to find families of Russian Arctic Convoy heroes