As a frontline police officer in Edinburgh, Graham Goulden had seen it all when it came to domestic abuse.

However, he is the first to admit that he and his colleagues haven’t always known how to deal with coercive partners and their terrified victims when called to their doors.

“In the 80s and the 90s we would just tell people to be quiet,” he reflects.

“We would tell them their neighbours were complaining and to just be quiet.

“You feel quite ashamed now, but that was the lens we viewed domestic abuse through at the time.”

For the last decade of his policing career, Graham worked as a Chief Inspector within Scotland’s world-renowned Violence Reduction Unit (VRU) as it expanded the remit of its work to tackle both crime and its causes across Scotland.

The VRU is credited with dramatically reducing violent crime in Glasgow at the time it was named the “murder capital of Western Europe”. It achieved this by being, to borrow a phrase from Tony Blair, “tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime” among gangs in Glasgow.

However, Graham’s work was to explore how situations could be defused prior to them ever occurring, with the help of those much closer to home.]

Making ‘bystander effect’ a thing of the past

The Mentors for Violence Prevention (MVP) scheme he helped to develop teaches youngsters to recognise the “red flags” of problematic behaviour, from sexting, controlling behaviour, bullying and harassment, and to intervene in a safe way.

In short, he wants to make the “bystander effect” a thing of the past.

“Back then (in the 80s and 90s) I was angry. I would interview countless people about violent incidents and many would say: ‘I knew something was going to happen,” he recalls.

“My response was always: ‘Why didn’t you do anything?’

“It was only through speaking to Jackson Katz (the American pioneer of the MVP approach) that I realised that we needed to understand why people don’t speak up.

“It’s clear people are scared and don’t know the full story, or are convinced that it’s not their business. People want to help but they just don’t know what to do.”

The idea of the MVP scheme is to equip youngsters – and others – with the mental tools they need to be able to approach a peer and “call them in” – a less confrontational and more positive way of addressing a person’s behaviour. They are also taught how to support victims and how to delegate the situation to responsible people, such as teachers or the police.

Graham continued: “How do bystanders bring them in and give them tools to be part of the solution – not just to intervene but to talk about issues like domestic abuse and sexual assault?

“When I joined the police I was given the power to arrest and search, cuffs, a radio and a baton. I was given tools to deal with a challenging situation.

“I’m not saying we give people batons, obviously, but we give them a toolkit in the same way and teach them how to use it.

“I remember the first pub fight I went to, in 1987. Me and my partner went to Leith Walk in Edinburgh and ran straight into the pub and we got absolutely battered.

“We got dragged out by our colleagues and they asked us: ‘What did you learn?’

“We should have called for backup. We hadn’t learned to use our toolkit properly. We need to do the same with society.”

An untapped resource

The MVP approach is currently used in 28 out of Scotland’s 32 local authorities, each at varying stages of deployment. It is effective because it relies on peers intervening on one another, rather than from authority figures.

And Graham hopes that its continued rollout will lead to fewer abusive partners being enabled to carry on with their practices.

“If you challenge a friend and say they are behaving inappropriately that can have a massive impact,” he says.

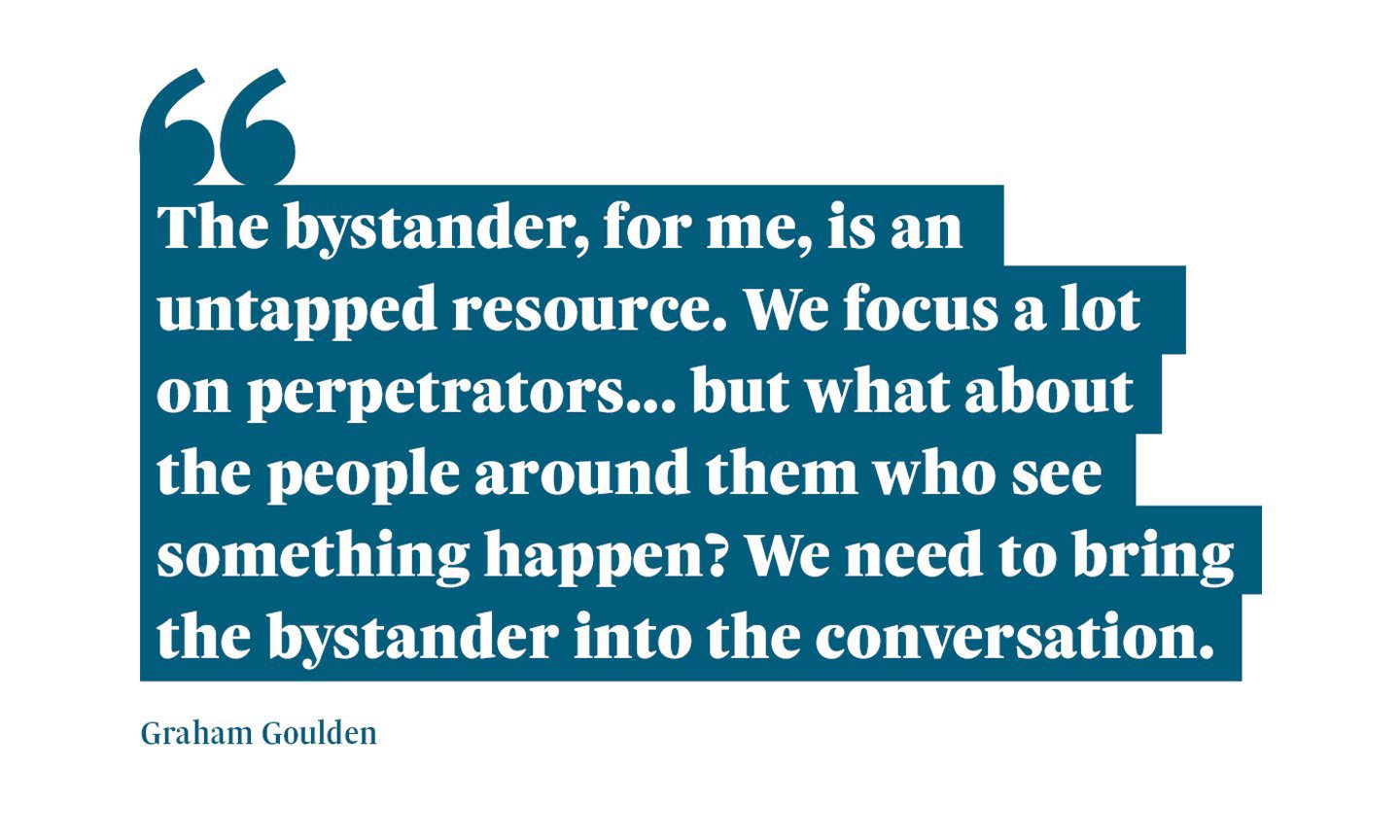

“The bystander, for me, is an untapped resource. We focus a lot on perpetrators, and that’s important because we need to tell them their behaviour is wrong, and we support victims because they deserve to be supported by the system and their friends and neighbours.

“But what about the people around them who see something happen? We need to bring the bystander into the conversation.

“We saw it with Harvey Weinstein – the silence of others that gives some abusive men what they feel is the permission to do what they want, and the kudos that what they do is okay.

“It’s about having the courage to challenge your friends and creating a space for conversation. There’s a social fear that we lose friends or people turn against us in a peer group – we need to help people overcome that. Perpetrators need to be held accountable.”

More awareness needed

After Graham retired from the police in 2017, the MVP Scotland scheme was passed into the hands of governmental body Education Scotland to continue its expansion

In that time, Police Scotland also trained over 14,000 officers and staff to recognise signs of coercive and controlling behaviours, while the Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act made such behaviours against the law. The Disclosure Scheme for Domestic Abuse Scotland was also introduced, allowing people to ask police if their partners have previous convictions for coercive conduct.

Graham continues to coach violence prevention techniques to private clients including sports teams and office-based workplaces through his business, Cultivating Minds UK while also keeping an eye on developments on his former patch.

“Policing of domestic abuse has changed and Police Scotland should be applauded for that.

“But we still have a lot of people who don’t know that controlling behaviour is against the law. There’s still more awareness needed out there in our communities. Domestic abuse costs us £23 billion a year (in England and Wales, and two women a week are killed in the UK.

“It’s fear and terror – that’s what coercive control is. Perpetrators putting fingers to mouths to say be quiet; the little, subtle things.

“I heard one example where police attended and the abuser came out the bathroom with a white towel over his shoulder and the victim’s demeanour completely changed.

“It turned out that was the towel he would use to cover her face and stop her making noise.

“Bystanders can spot subtle signs – people being upset, always texting partners and trying to laugh it off, those can be significant.

“I’ve trained door stewards and bar staff to spot abusive behaviours and on one occasion a steward stopped a drunken couple and spoke to them, and the woman didn’t know who she was with and they were able to prevent what could have been a rape or a sexual assault.

“Policing has upped its game in Scotland – we need to do that as a society too, and we can.”