It is 30 years to the day since a government minister visited Britain’s ‘death island’ to declare it safe.

Life on this once-popular picnic spot and bird sanctuary less than a mile off the Scottish coast has never really returned to normal, however.

Bombed with anthrax during the Second World War as part of a top-secret biological weapons research programme, rendering it a no-go zone for 50 years, this is the story of Gruinard.

The idea

Hammered by the Blitz and on the retreat in the Far East, Britain’s future looked bleak in late 1941.

Surrounded by Nazi-occupied Europe and fearful of invasion, a desperate Winston Churchill turned not to military planners, but to the UK’s scientists for help.

Dr Paul Fildes, director of biology at the Ministry of Defence’s secretive Porton Down lab, was tasked with developing a biological agent to halt Hitler.

Operation Vegetarian was born.

After a few months of research and discussion, Dr Fildes and his team settled on an idea to use a virulent strain of bacillus anthracis – otherwise known as anthrax – against the German population.

In Dr Fildes’ view, given the serious infectious nature of the bacteria, particularly in animals, if Britain were to air drop “cattle cakes” stuffed with anthrax over Europe, the meat and dairy supply would be virtually eradicated and there would also likely be a mass outbreak among the human population – causing panic and it was hoped, a possible end to the war.

Excited by the idea, in 1942 British military authorities urgently wanted to put the plan to the test – but where and how?

The location

Aware anthrax was a highly infectious and deadly agent, the MoD needed a remote and sparsely populated location to test the plan.

Whitehall’s eyes scoured the map and eventually stopped on an obscure mile long island in northwest Scotland.

Gruinard, which lies just off the Wester Ross coast about halfway between Gairloch and Ullapool, was promptly surveyed by MoD planners in 1942.

They knew there was something going on or they wouldn’t have paid up quite as quick as they did.”

While the island may have been remote and lost the last of its human residents at the turn of the 20th Century, it remained a popular location with picnickers and resting fishermen at the time.

In a 1934 travel feature, published in the Press and Journal, the area was given a glowing review.

“Gruinard Bay beats them all, it is broad and northwards, the sea is gemmed with little isles, its coasts are infinite in their variety of bold high headlands, little fresh creeks and sandy shores.”

The island formed part of the sprawling Eilean Darach estate, which was bought in 1926 by Rosalynd Maitland. Upon her death some years later, ownership passed to her niece Molly Dunphie and husband Colonel Peter Dunphie – a close wartime confidant of Churchill.

The family were paid £500 by the MoD and the island was requisitioned.

With the method and location secured, a date was set for the experiment.

The experiment

In late 1942 a platoon of British troops and scientists rolled into Gruinard Bay, their mission – to test the viability of anthrax bombs.

Porton Down scientist Sir Oliver Graham Sutton was put in charge of the fifty-man team to conduct the trial, with fellow scientist David Henderson in charge of the germ bomb.

Footage of the experiment, declassified in 1997, shows soldiers loading sheep into a dinghy on the mainland and then rowing across to Gruniard.

Once ashore, the sheep were herded into an enclosure – described as the “exposure zone”.

I saw a cloud running above the earth coming towards these animals, they were tied up in a line.”

Soldiers, wearing respirators and protective clothing, can then be seen loading the “anthrax bomb” – gas canisters filled with spores – into a mortar to fire on the area.

In all, 22 bombs were fired onto the island by mortars and another, larger bomb was dropped from a Wellington bomber cruising above at 7,000 feet.

An eyewitness, speaking to the BBC 20 years later, said: “I saw a cloud running above the earth coming towards these animals, they were tied up in a line”. Before trailing off and shaking his head, the farmer said “anthrax”.

All 60 of the sheep rowed across to Gruinard died within a matter of days.

After autopsy, several of the animals were destroyed in a makeshift incinerator on the island, but the majority were – according to many accounts – buried and then blown up with a 1,000lb of explosives.

The experiment was deemed a success and in secret Churchill ordered the production of five million contaminated cattle cakes.

As it was, events took over and by the time the cakes were ready, in 1944, they were deemed unnecessary and destroyed, but Gruinard remained.

The aftermath

Anthrax, the fifth plague of Egypt mentioned in the Book of Exodus, can stay in the ground for more than a thousand years.

Gruinard, coated in a highly contagious strain, thus became one of the most dangerous places on earth and was placed under a tight quarantine.

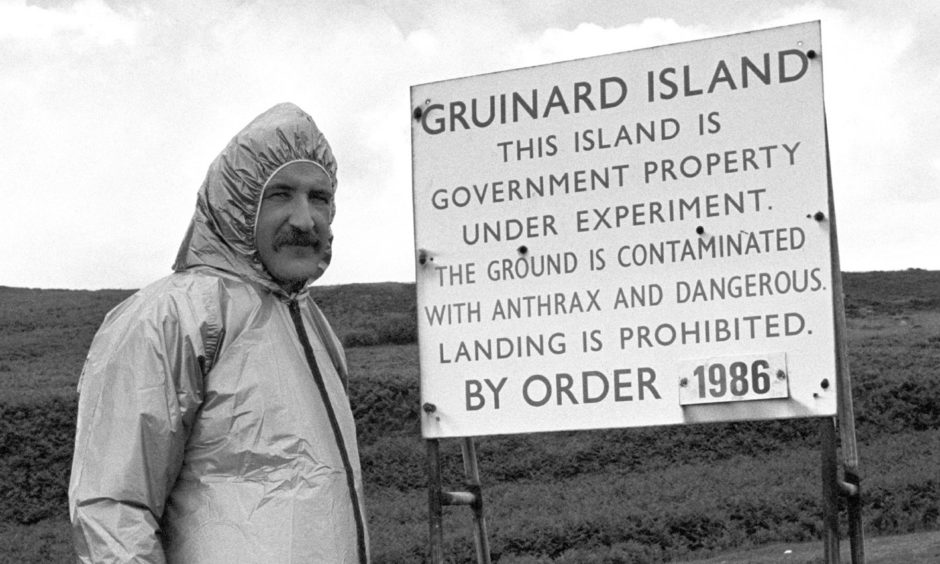

Metal signs in Gruinard Bay warned people to keep away from the island as it was government property, but given the top-secret nature of Operation Vegetarian the public were not made aware of the actual danger.

In the early years, Highlanders understood only that the island had been used by the MoD for some mystery experiment.

Rumours of poison spread quickly among locals however, after one of the sheep from the original experiment washed ashore.

It was almost used as something to frighten the kids with.”

Its carcass was set on by a farmer’s dog, which became violently ill. Shortly after several farm animals died with a mystery illness.

One local told the BBC in a 1962 report that government officials, based near Gruinard, had paid compensation “without any quibble.”

“They knew there was something going on or they wouldn’t have paid up quite as quick as they did,” the local said.

As the forties slipped into the fifties and Britain’s fear turned to nuclear war, Gruinard became something of a myth.

“There was a lot of folklore around about it”, Highlands MP Jamie Stone remembers.

Mr Stone, who was born 12 years after the operation, said: “It was almost used as something to frighten the kids with.

“I can remember being about 10 taking trips to Wester Ross with my family in the car, my old man would point at Gruinard and say that is the poisoned island and no one must ever set foot there, it’s got a deadly germ on it.

“It certainly sent a shiver down my spine!”

Over the next 40 years the island got occasional headlines if a fishing vessel strayed too close, but in reality it was largely forgotten.

The warning signs meant nothing to them. They hauled their boat ashore unpacked a picnic and spent the day fishing – unaware of the consternation on the mainland.”

“Towards the end of the 1970s two European backpackers, unable to read English, caused a minor storm when they decided to row to the island for a picnic.

A report in the Press and Journal from the time read: “Two holidaymakers – Peter Schultz from Germany and a Belgian, Paul Dewet – decided to row to Gruinard while on a fishing trip round the Scottish Islands.

“The warning signs meant nothing to them. They hauled their boat ashore unpacked a picnic and spent the day fishing – unaware of the consternation on the mainland.

“Police from a nearby Nato base had spotted them on Gruinard and when the pair rowed back they were puzzled to find a reception committee dressed like spacemen waiting for them.

“The tourists were stripped of all their clothes scrubbed in disinfectant from head to toe, all their possessions including their rubber dinghy were sent to Porton Down for tests.”

The unfortunate holidaymakers were allowed to continue their trip and told to contact a doctor if suffering from anthrax symptoms.

There was local anger around the same period after the island was placed on a long-list of potential sites to dump nuclear waste, but energy officials concluded the rock composition of Grunaird wasn’t suitable for the task.

The memory of Gruinard was about to resurface in a big way, however.

The terror cell

“Police probe Gruinard claim”, screamed a P&J headline in late 1981.

The story? A special task force had been set up to investigate claims that contaminated soil had been taken from Gruinard and posted to Porton Down.

A terror cell calling themselves the Dark Harvest Commandos took responsibility and in a letter to newspapers, claimed they had 300lbs of the soil ready to send to other targets.

Sure enough the group, thought to be made up of scientists and locals, posted soil to the Conservative Party conference in Blackpool in 1981 sparking a national panic and international story.

The group’s demand was a simple one: clean up Gruinard.

Local opinion was divided, with many condemning the actions as irresponsible, but a few dissenting voices offered support.

A local businessman, John Macrae, told the P&J at the time: “It is a potential time-bomb.

“We have a living example of the Second World War still under our noses.

“It is very highly contaminated island; in fact, it is as contaminated today as the day the experiments were carried out.”

The police manhunt for the group never produced an arrest, but shortly after the incidents the government sent scientists to the island to examine the possibility of making Gruinard fit for animal and human habitation once more.

The clean-up of Gruinard Island

Government scientists and MoD officials had visited the island periodically to test the soil between 1943 and 1981 – always with the same result.

There was still a deadly amount of anthrax in the ground.

An MoD analysis in the mid-seventies concluded that any clean-up operation would run into the tens of millions of pounds and that it would be more cost effective to keep the island in quarantine.

After the Dark Harvest incidents, however, a new approach was taken and advances in technology meant the clean-up could be done for as a little as £500,000.

In 1986, 44 years after the bombing, a Leicestershire disinfectant firm arrived on the island.

Wearing full hazmat suits and respirators, the team first burned off vegetation in the “exposure zones” and then sprayed the ground with a combination of sea-water and formaldehyde.

The process was repeated a number of times to ensure the mixture had soaked deep into the soil.

A year later, a sample of the soil was collected and sent to Porton Down for tests.

The samples showed positive signs, but it would be another three years before the island was officially declared “safe”.

The return to ‘anthrax island’

On an overcast, rainy day in April 1990, junior defence minister Michael Neubert arrived at the Wester Ross coast. With him was a pack of expectant reporters and photographers.

Iain MacDonald, a retired BBC Scotland journalist, remembers the day well: “It was just totally surreal.

“Gruinard was a story I knew very well, because we’d spent quite some years trying to track down the people involved in Dark Harvest.

“Now here we all were on a boat heading across.

While we cannot say there is absolutely none, we can offer the assurance that we can find none.”

“The experts claimed it was completely safe but you don’t ever know for sure, perhaps that was why Neubert didn’t look particularly enthusiastic about his mission, or maybe it was the miserable weather.

“Whatever the reason, I remember feeling nervous about going across in that boat.”

Those assembled were right to be nervous, for the then-Portdon Down director Dr Graham Pearson’s reassurances were less than cast iron.

“We cannot sample every square centimetre of the island, but we are very confident that in the area of the island where there were anthrax spores we have killed them.

“While we cannot say there is absolutely none, we can offer the assurance that we can find none.”

In the event, Neubert did survive the picture opportunity, but didn’t survive a reshuffle just two months later when Margaret Thatcher unceremoniously dumped him.

After the island was given a clean bill of health, it was sold – as per the agreement signed in 1942 – back to the original owners for the same price, a mere £500.

Col Dunphie, then 83, reflected to the Press and Journal: “The family were being helpful in time of war in agreeing to let them experiment on Gruinard – although we couldn’t have stopped them, anyway.

“I’m only baffled and sorry that, for such terrible experiments, they chose Gruinard, so near to the mainland and not one of the islands 20 or 40 miles out to sea.”

He spoke of his ambition to visit the island once more, but said: “This time around Gruinard will be a place rather full of ghosts for me, because all the people I used to go with are no longer with us”.

In the years since the island was declared safe, it was portioned off from the Eilean Darach estate and sold to a mystery buyer in the nineties.

Nowadays it draws the occasional “dark tourist” – those who enjoy visiting places marred by death and tragedy and it remains a point of fascination on internet forums and blogs.

The story of the now-barren island should, however, as so many have argued down the decades, serve as a permanent reminder of the evils of chemical and biological warfare.