It was one of the worst setbacks for the Allies during the Second World War and had a grievous impact on thousands of young men from the north and north-east of Scotland.

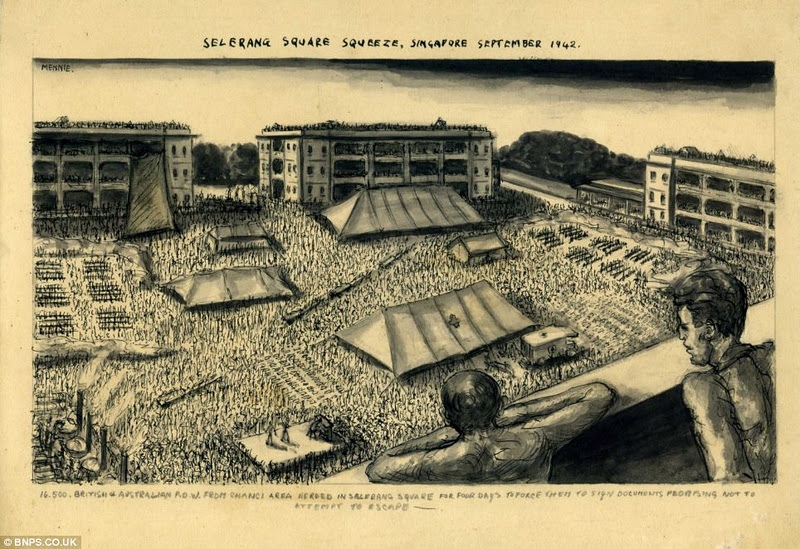

Winston Churchill declared that the fall of Singapore to the Japanese on February 15 1942 was the biggest disaster and largest capitulation in British military history.

And almost 1,000 members of the 2nd Battalion Gordon Highlanders were among the 60,000 British and Australian troops who were caught up in the catastrophe.

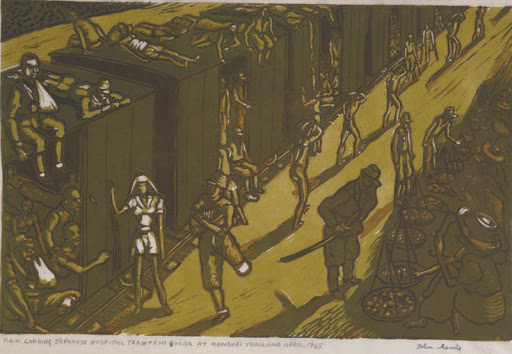

As prisoners of war, they spent the next three and a half years as virtual slaves of the Japanese with many in their ranks involved in building the infamous Thai-Burma Railway and other projects in the newly-occupied Japanese territories.

Given the privations they suffered, which have been highlighted in films such as Bridge Over the River Kwai and Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence, it was hardly surprising that those who survived rarely spoke about their ordeal, and they returned home after VJ Day on August 15 1945 with relief in their hearts as much as jubilation.

These men were often worked to death on a meagre diet of watery rice, with little or no vegetables or meat which led to malnutrition and starvation.

Their ordeal was compounded by brutal treatment from their captors who ignored the tenets of the Geneva Convention, designed to protect prisoners of war, while a range of tropical diseases such as malaria, cholera and dysentery inflicted a dreadful toll on men whose courage was tested to the limit – and often over it – on a daily basis.

The result was that almost 400 of the Gordon Highlanders – 40% of those incarcerated – died at the hands of the Japanese.

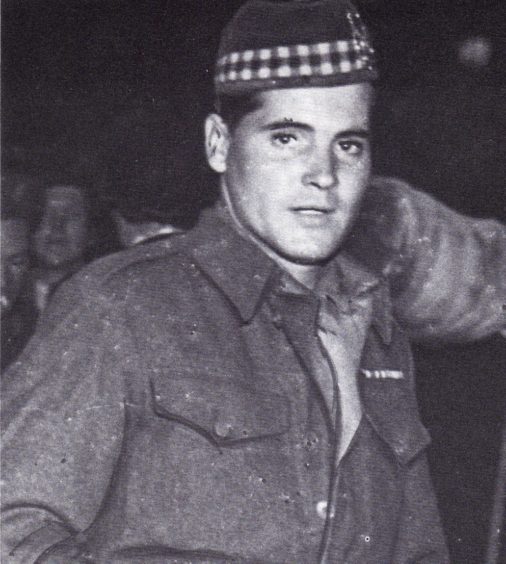

Alistair Urquhart from Newtonhill in Aberdeenshire was one of the troops who came home, despite being involved in a series of appalling events, and wrote vividly about his recollections of the conflict in The Forgotten Highlander.

He said later: “Many of us hardly knew where Singapore was before we travelled out there – but those of us who were lucky enough to come home never, ever forgot it.

”There were so many of my pals who never came back. They were lads who went over there to serve their country and they had absolutely no idea what lay in store.”

By 1945, the tide had turned against the Japanese but they fanatically fought on, oblivious to an escalating number of casualties as mayhem reined in the jungle.

The Scottish prisoners had already endured more trials and tribulations than most of their compatriots, but were still to confront the terrifying reality of the atomic age.

Stewart Mitchell, the historian at the Gordon Highlanders Museum in Aberdeen, has chronicled the shocking events which hastened the end of the hostilities in the Far East in his evocative book Scattered Under the Rising Sun.

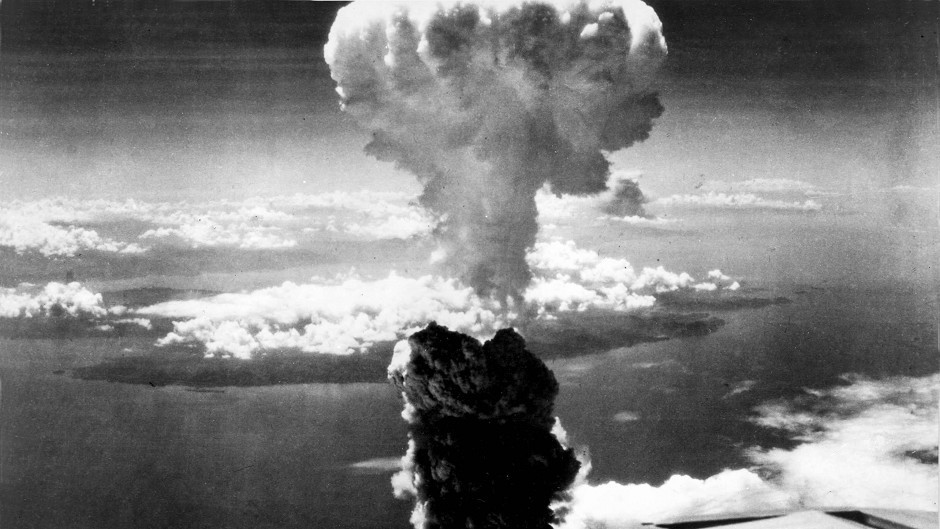

Mr Mitchell said: “The morning of August 9 was a fine day and Bill Young from Turriff, who was in bad physical shape, suffering from malnutrition, was sitting overlooking Nagasaki Bay while other Gordon Highlanders, Billy Burns, from Inverurie and George McNab, from Peterculter, were clearing up rubble and other debris from previous air raids and Mr Urquhart was nearby tending the Japanese officers’ vegetable garden.

“The trio were all survivors of the Thai-Burma ‘Death’ Railway and shipwrecks in the South China Sea, but they were now in captivity at Nagasaki.

“Suddenly, they were stunned by a blinding flash which was followed by a terrific boom. Billy Burns saw a colossal cloud of smoke rising up from the city and initially thought that an oil dump had been hit.

“Bill Young, from his vantage point above the city, saw the cloud of smoke and thought an Allied plane had been hit, but noticed the cloud began to connect to the ground until a huge black mushroom cloud grew and grew.

“Day turned into night as it blotted out the sun, an eerie silence descended and everything became coated in black fallout dust.”

This was the detonation of a second atomic bomb by the Americans – the first of which devastated Hiroshima – and just a few days later, on August 15, the Japanese surrendered unconditionally.

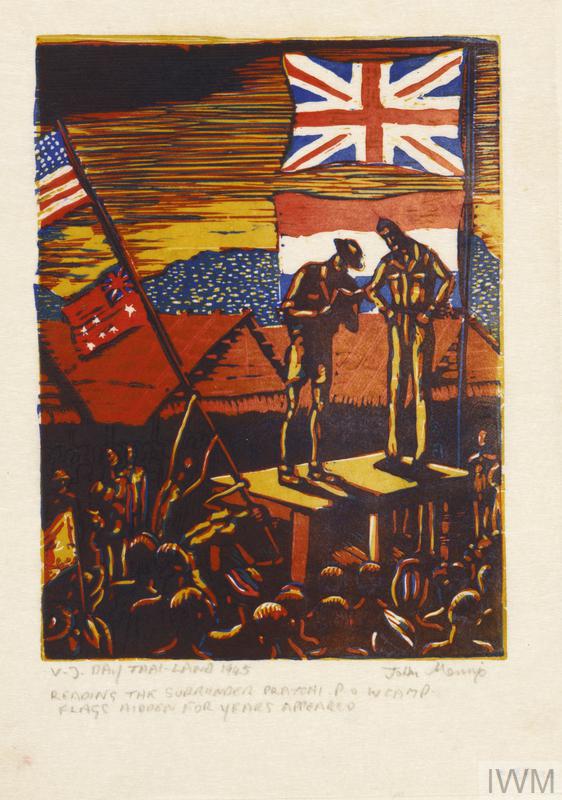

However, the prisoners were not given the news that the war was over and they were free at last for several days with the Japanese, even in defeat, not wishing to lose face.

Jimmy Mowatt, from Laurencekirk, and Willie Morrison, from Glasgow were among the soldiers working near Tokyo after the cessation of the conflict.

Eventually, their labours were interrupted when a Japanese officer announced: “The war is over and I hope you get back soon to your loved ones” – a statement which astounded them considering how they had been treated by their captors.

The POWs in Japan and Taiwan were subsequently repatriated by a voyage across the Pacific where they were given time in Western Canada and the USA to build up their strength as the prelude to embarking on a transcontinental rail journey to New York, where the liner RMS Queen Mary was waiting to take them home.

The men who had been working on the Thai-Burma ‘death’ railway were flown to Rangoon, Burma and returned to Blighty, via the Indian Ocean and Suez Canal.

Mr Mitchell said: “It was not only in Japan that the prisoners found the sudden capitulation of the Japanese hard to believe.

“At Ubon in Thailand, where Willie Niven and a number of other Gordons were constructing a runway on an airstrip, Willie was in a bad way and appreciated that he wouldn’t survive much longer.

”He had caught malaria no less than 20 times during his incarceration and his stomach was swollen up with beriberi.

“He also heard rumours of the Japanese surrender, but only believed it when a truck stopped at the camp, and an American officer got out and announced the war was over.

“Strangely one of the first things he said was: ‘There is a Labour Government in power in Britain’, which Willie didn’t care about in the least at that stage, but he was very pleased to receive a gift of razors and cigarettes.“

There were a few heartwarming stories in the midst of abject adversity.

While he was a prisoner at Chungkai in Thailand, in 1944, Corporal Willie Gray, a Gordon Highlander, spotted two ducklings being swept down the River Kwai, which was in flood.

He dived into the water and saved the ducklings, but only one of the little creatures survived, which he named Donald after the famous Walt Disney cartoon character, and considered it appropriately Scottish – although the bird was actually a female.

When the Japanese guards threatened to kill and eat it, Cpl Gray had to think on his feet and told his interrogators that Donald was a sacred duck, which, to his surprise, did the trick and the fortunate bird was spared.

Later, when repatriating the POWs in 1945, the authorities insisted they should take nothing home for fear of disease, and all their clothes were burned and new kit issued.

This edict also extended to animals (and birds), but undeterred, Cpl Gray bound Donald’s wings, beak and legs and smuggled her aboard the RMS Corfu inside his new kit bag.

Unsurprisingly, during the long voyage back to Britain, Donald was discovered on deck and an announcement was made by the ship’s captain over the public address system demanding to know: “Who owns this bloody duck?”

Cpl Gray owned up and the captain ordered the cook to come on deck. But, after a debate among the soldiers and crew members, the conclusion was reached that one duck, even as soup, would not go far. Almost unbelievably, Donald was saved again.

Mr Mitchell added: “As the vessel left the warm latitudes, Donald, who was after all a tropical duck, started to feel the cold, so some of the Gordon Highlanders unravelled some woollen clothing and knitted a woollen pullover to keep her warm.

“Eventually, they arrived in Southampton, in early October 1945, and travelled home to Aberdeen by train. The press photographers were delighted to snap her photo at Aberdeen Railway Station when William Gray was finally reunited with his family, whom he had not seen for eight years.

“His family lived at Forgue, near Huntly in Aberdeenshire and a short time after his repatriation, he took a trip, by bus, to travel the few miles to Aberchirder, to visit the parents of Alex Gibb, his friend and a fellow Gordon Highlander, who had died of malaria in Borneo.

“Locals were surprised and delighted to see Willie getting off the bus with Donald waddling down the street after her beloved master. Later, the pair of them visited the local pub and were given a glass of beer which they both clearly enjoyed.”

Sadly, though, such tales were the exception rather than the rule.

With the exceptional casualty rate among the prisoners of the Japanese, a great many of the Gordon Highlanders lost friends while they were incarcerated.

One of the troops who returned to his native Glasgow was Bill Hunter who had joined the Gordons with his two friends, Mick Griffin and Jack Casserly.

As prisoners, the trio were being forced marched in northern Thailand in June 1943 when Mick and Jack found their comrade close to death through exhaustion, disease and malnutrition, lying at the side of the track.

Although in fragile shape themselves, they helped him to the next camp where Bill was able to recover. But tragically, as if to emphasise the water-thin margin between survival and death, both Mick and Jack died soon afterwards after contracting cholera.

Mr Hunter survived the war, but weighed less than six stones when liberated and yet went on to have 13 children, all of whom had their own families.

Many years after his death, Bill’s son, Kevin, was attending a concert in Toronto where the star of the show was the popular Scottish-Canadian singer John McDermott, who was also originally from Glasgow.

He introduced one of his songs, entitled The Gift of Years by telling the story of his uncle, Mick Griffin. Since his father rarely spoke about the war, Kevin was totally unaware of the part which Mr McDermott’s uncle had played in his father’s survival.

The singer’s interpretation of that act of kindness was that Bill’s survival had resulted in a total of 750 years of new life for Bill and his offspring, hence the song title.

Kevin Hunter was dumbstruck upon realising that the singer was talking about his father and how strange the coincidence that here he was, more than 3,000 miles from home, listening to the story.

During the intermission, he went backstage and introduced himself to Mr McDermott. At the start of the second half of the show, the singer asked for the lights to be brought up in the auditorium and introduced Kevin to the audience where he received a rousing reception. These families never lost contact after their shared memories of war.

Although VJ Day was celebrated nationally, these prisoners didn’t reach home until the end of October 1945 by which time the majority of people in Britain had moved on and just wanted to forget the war.

This meant that, apart from family reunions, they did not receive the heroes’ welcome which they deserved. And many of the soldiers lamented the lack of focus on the conflict in the Far East, compared to the attention lavished on the European arena.

That feeling was not just harboured by the POWs, but the two battalions of Gordon Highlanders and myriad other servicemen from Scotland who had fought the Japanese in Burma and also returned home some time after VJ Day.

They dubbed themselves The Forgotten Army.

On the 75th anniversary of their liberation, it’s time to commemorate their sacrifice properly.