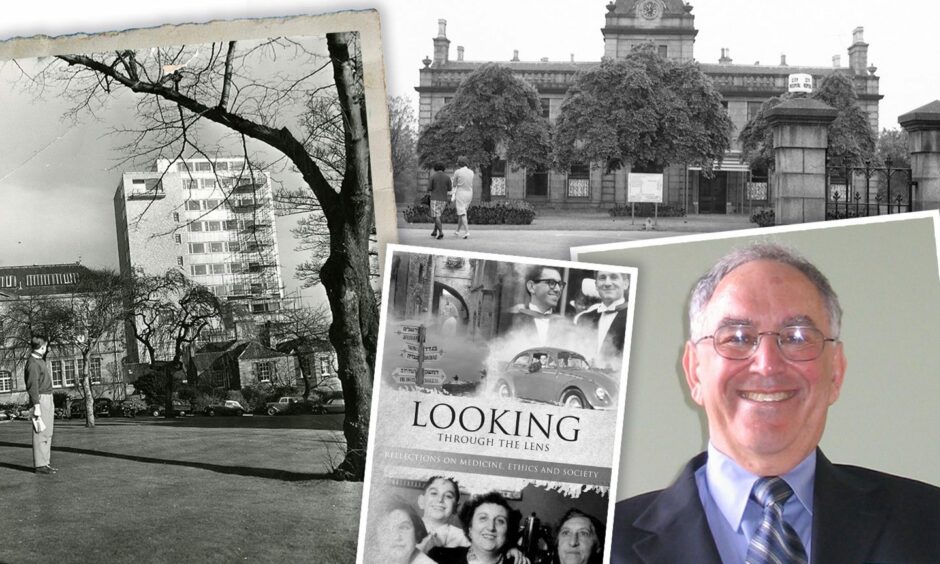

One of North America’s best known geriatric medical specialists has revealed in his memoir the powerful influence Dundee medical school and Aberdeen City Hospital had on his life’s work.

New Yorker Dr Michael Gordon’s career took him all over the world from Brooklyn to Europe, behind the Iron Curtain, to the Middle East, and finally to Toronto University, where he is emeritus professor of medicine.

But as he enjoys retirement surrounded by animals, both domestic and wild, listening to music and spending time with his family, Michael’s thoughts often turn to Scotland and the two doctors, both named Walker, who influenced him most.

It wasn’t in his original life plan to find himself in Aberdeen or Dundee, in fact engineering was Michael’s first thought as a career.

Born in Brooklyn in 1941, Michael lived briefly in Dearborn, Michigan where his father worked as a civilian engineer for the American Department of Defense.

They returned to Brooklyn at the end of the war and Michael attended Brooklyn Technical High School, hoping to become an engineer like his father.

A trip to Europe and some seminal reading, including A J Cronin’s The Citadel and Paul de Kruif’s Microbe Hunters dramatically changed his thinking, and he switched from engineering to medicine.

At this point, fate intervened.

Michael was offered the chance to attend St Andrew’s University medical school in Dundee, and jumped at the chance.

He was later to learn that he only got his place because another young medical student had died, something he never forgot.

Culture shock

Dundee was a bit of a culture shock to the young Brooklyn lad.

Michael writes: “Once I accommodated to the dreary gray weather, the strong and at times unintelligible, Dundee accent, the paucity of any food worth eating other than fish and chips, and the damp cold of the housing, I had a fabulous experience.”

Needless to say the chippie of choice was the legendary Deep Sea restaurant in the Nethergate.

Dundee was where Michael was introduced to geriatric medicine.

He says: “The geriatric rotation and ward proved to be one of my favourites because of the instructors and wonderful experiences with the ‘auld wifies’.

“One of the geriatric wards in Maryfield Hospital was made of a large room with a potbelly stove at its centre.

“In the evening all those women patients who were able sat around in their easy chairs, drinking tea, chatting and knitting.

“It was a glorious warm vision and experience as they just loved us medical students.”

On to Aberdeen City Hospital

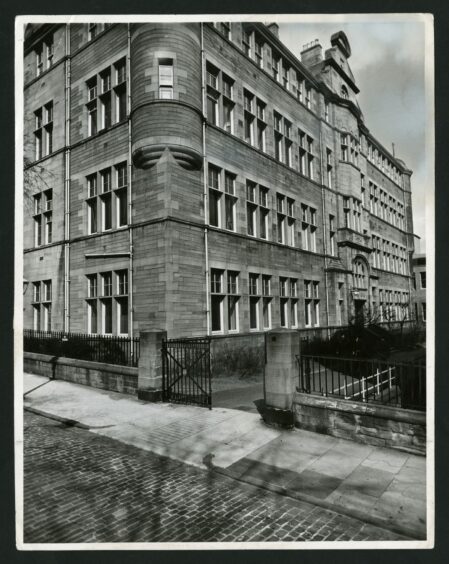

Michael graduated from St Andrew’s medical school in 1966 and went on to a six month internship at Aberdeen City Hospital.

‘The silver city with golden sands’ as the Granite City was described in a 1950s guidebook, was a place Michael would never forget.

Heading there from Dundee, he found himself following one of his favourite teachers, William Walker who had been recruited as Chief of Medicine.

Walker was born in Dundee, a polymath, boxer and war hero.

Michael said: “I came to respect and emulate this physician during his medical teaching in Dundee, but also for his weekly late-afternoon seminars in ethics which were open to all, including any student from any faculty.

“It ultimately influenced me, years later, to study medical ethics at the University of Toronto.”

Aberdeen was also a culture shock for the young New Yorker, but in a different way from Dundee.

Who remembers the Quonset huts?

Michael writes: “I had no idea what I was getting into, but upon my arrival I saw a large tract of land studded with a dozen or more Quonset huts, remnants of the Second World War which were fashioned into medical wards initially as an infectious disease unit.”

Some of the local lingo puzzled Michael, who writes: “When I was shown to my digs, the woman in charge of the house staff’s wellbeing asked me in her lilting Scottish accent, ‘Would you like me to knock you up in the morning?’

“My understanding of the phrase ‘knock up’ had to do with impregnation so I did not realize it meant to knock on the door to wake someone up.”

Fuelled by a breakfast of porridge and a full Scottish fry-up Michael would begin his day.

His first day was a baptism of fire.

He had his first encounter with ‘Sister’, dressed in the traditional uniform of the time, with a full blue skirt covered by a white apron and white hat pinned to her head — “she was like a ship in full sail,” says Michael.

Life-saving lumbar puncture

But it was Sister who guided Michael in his first real lumbar puncture to save the life of a patient in extremis with septicaemia and meningitis.

He writes: “I turned to the Sister and said, ‘I have only done one of these in my training’ to which she said, ‘You’ll be fine.’”

The procedure went well and Michael overheard the sister whispering on the phone to the lab, “He is a good lad.”

Reputation of Dr Michael Gordon established

Praise indeed, and now Michael’s reputation was established.

Just as well, as that same night a three-month-old baby came in with suspected meningitis, requiring a lumbar puncture, even more difficult in such a tiny body.

After successfully performing the lumbar puncture, Michael had a quick look down the microscope at the spinal fluid and realised the baby’s illness was h.influenza meningitis.

He promptly prescribed the correct antibiotic, and the baby pulled through, to the joy of the mother.

“I remember thinking, ‘I really did save a few lives on the first two days of my internship.’”

Michael also encountered remnants of the infamous 1964 outbreak of typhoid fever in Aberdeen.

“Many citizens were stricken and it was a real epidemiological challenge,” Michael writes.

“It was finally traced to a downtown Aberdeen Low’s Supermarket’s meat slicer onto which a tin of tainted corned beef from South America was contaminating everything that went through the slicer.”

For Michael, the highlight of his six months was the presence of William Walker.

“He was a great physician and a great man.

“We continued contact for many years thereafter. I will never forget him and my entry into the world of face-to-face medical practice.”

There was another influential Dr Walker in Michael’s life at this time, James Walker, head of obstetrics and gynaecology in Dundee.

The reason for Michael’s Scottish surname

James Walker made it his business to find out why a ‘Yank’ like Michael had a Scottish name like Gordon.

While carrying out Michael’s oral interview on midwifery and gynaecology, Dr Walker demanded to know the provenance, no matter how long it took to tell the tale.

Michael explained at length that his ancestors were Lithuanian Jews and took the name Gordon in deference to the 17th Century general Patrick Gordon of Auchleuchries in Aberdeenshire.

“He was a dear friend of the Czar… Jews hoped that by adopting the name Gordon they would be looked on with favour by the Czar.

“Our family had the name Gordon for many generations and brought it to America with them.

“Another segment of the community went to South Africa where there are numerous Jewish Gordons.”

Impressed

The story impressed Dr Walker, who listened intently.

There were now thirty seconds until the end of the oral exam.

“Dr Walker said ‘oh dear me’ as he looked at his watch. ‘Give three characteristics of pre-eclampsia’.”

Michael spun out his answer by speaking as slowly as possible to reach the end of the allotted time.

“As I walked out the door I heard him whisper to himself, ‘very good, very good’ in his thick Dundee accent.”

Top marks

Michael scored the highest mark possible, and was awarded the prize for Midwifery and Gynaecology.

He used the £500 prize to carry on training in Israel, opening a new chapter in his life.

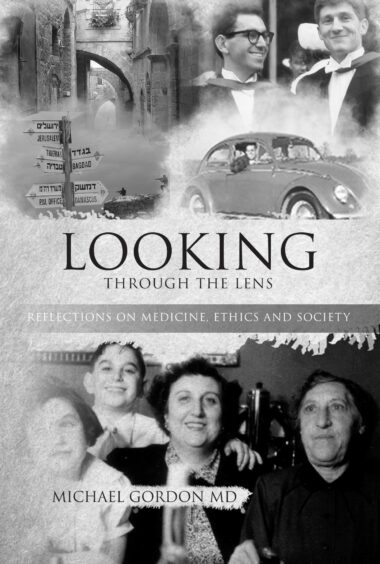

Michael tells his life story in his new book, Looking Through the Lens: Reflections on Medicine, Ethics and Society, available on Amazon.

Conversation