Good Friday, 29th March, 1991 wasn’t such a good day for Paul Hyett, in fact it was nearly his last day on earth.

He’d been persuaded by a friend to tackle a couple of Munros “somewhere in the middle of Scotland” to help him get over the break up of his first marriage.

After successful climbing the mountain next to Ben Alder in the Cairngorms, the pair headed along the ridge towards the Ben, thinking to conquer two Munros in one day.

Disaster struck

But disaster struck when Paul, a medical photographer at the Royal Marsden Hospital in Chesea, fell into an icy, wet cavern next to a waterfall, completely mashing his right leg, and sending his thigh bone into his groin.

“I must be the only man in Britain whose femur nearly gave him a vasectomy,” Paul says.

This is excruciating image hardly begins to describe what the 37 year old went through that day.

The accident happened at 4.30 in the afternoon, and it wasn’t until the early hours of the following day that the Cairngorm Mountain Rescue team reached him, managed to get him onto a stretcher, lifted him out of the cavern and over to the rescue helicopter from RAF Lossiemouth.

Paul spent eleven hours lying in the dark and a pool of ice cold water with water raining in for eleven hours, while he lost half his blood into his right leg.

Paul’s will to live

On his own while his companion, Mel, went for help, he had time to review his life flashing before him and decide he was determined to live.

He said: “There were a number of times I though I was going to be taken out in a body bag, but then I thought that’s going to upset my parents, my family.

“I’m not having this. I’m not being taken out in a body bag. I want to live.”

He managed to keep himself awake as he grew more and more tired and cold.

Things improved once Mel came back with someone from the bothy named David and they started to brew up hot chicken soup.

Two hours later Cairngorm Mountain Rescue Team announced their arrival, a moment which makes Paul well up to this day.

It would be three long months before Paul could walk properly again and resume work.

“I can’t praise and than the staff at Raigmore hospital enough,” Paul says. “I hadn’t just broken my leg, it was smashed and bits of bone were all over the place.

“I had to have a blood transfusion, but turned out to be allergic to the blood, and had to have another one.

“I wanted to shave at one point, but the staff were reluctant to give me a mirror.

“I soon realised why, and why people had been staring at me, horrified. I wasn’t just white, but a kind of Dracula greeny-white from the loss of blood.”

Death wasn’t far away

Even lying on the ward, death seemed to be coming for Paul as he saw darkness closing relentlessly in on him.

“So I got up onto my crutches and went down the ward to visit another guy who had been seriously injured on the mountains at the same time as me. The feeling passed.”

The incident changed Paul’s life forever.

“I saw life was for living now — pointless saving for a rainy day,” he says.

Unusually, he has stayed in touch with his rescuers—most rescuees don’t— taking part in gruelling sponsored walks to raise funds for CMRT until now, aged 69, his knees won’t let him.

“Simply put, I owe my life to the Cairngorm Mountain Rescue Team. They put their lives at risk to save mine.”

The current team is around 40 dedicated volunteers, but 60 years ago, things were very different.

Willie Anderson has been a member of the team since 1981, and is the current team leader.

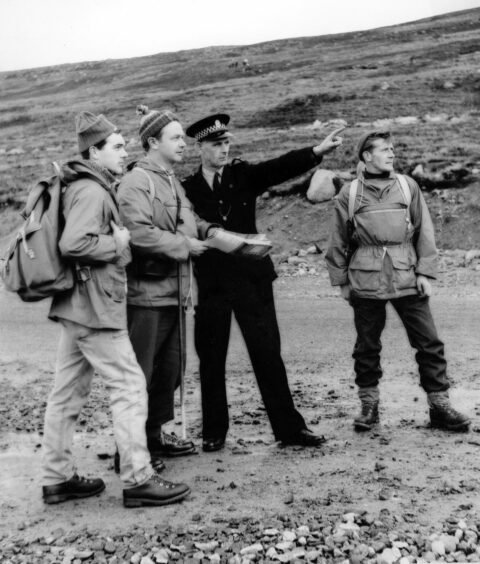

He said: “Mountain rescue work used to be done by game keepers, forestry and estate workers, people who knew the terrain well, and the police.

“It was pretty informal, guys going out with anoraks and walking sticks.

“But then folk started coming to the hills more and more, and the police couldn’t cover it all so a group of locals decided to put out an advert and form a team.

“The early team leaders were Tommy Paul, Peter Bruce and Alistair McCook.

“After Alistair came Molly Porter, from 1972 to 1981, the first woman team leader, who was there when I joined.”

Willie, originally from Glasgow, was a technical teacher at Kingussie High at the time.

He was inspired to join the team one night in the pub when he heard team members including John Allen talking about their rescue work in the hills.

John , who would become team leader for 18 years in 1989, took part in over 1000 rescues during that time, for which he was awarded an MBE in 2001.

Willie applied to join, and was interviewed by Molly Porter.

“She was looking for a good decision maker with a cool head, not prone to panicking and not fazed by weather, casualties or fatalities.”

Molly chose well, for Willie would follow in John Allen’s footsteps as the team leader in 1997.

He’s witnessed a huge evolution in the equipment available to modern mountain rescue teams.

“In the old days we had hand-held radios. Now we’ve got mobiles, GPS, the search and rescue smartphone app Sarloc, drones with thermal imaging, personal locator beacons.

“It all helps, but it can’t replace boots on the ground.”

The team also benefits from medical advances like modern analgesics and light-weight oxygen cylinders.

Training is serious, and ongoing.

The team put their lives at risk every time they head out on a rescue, but it’s a managed risk, Willie says, and far outweighed by the satisfaction the team feels after a successful rescue.

“We know there are people out there who are going to die without help, leaving devastated family and friends.

“It’s a great feeling. The team has saved hundreds of lives.”

People who get into difficulties in the Cairngorms don’t always receive public sympathy, for going out ill-clad, ill-shod, ill-prepared, relying too much on their mobile phones.

Willie takes a different view.

“They don’t plan to have an accident,” he says. “Despite all the publicity folk still go out ill-prepared.

“Some of the worst are hill-runners who go out in tee shirt and shorts, with tiny packs.

“You don’t even need to break a leg, but if you can’t get back to the car park you’re in difficulties.

“One bad decision and everything can snowball.”

The winter rescues are the most serious and demanding for the team.

Memories of the 1971 Cairngorm Plateau disaster in which six teenagers and one of their leaders died, casts a heavy shadow over everyone involved at the time.

Willie said: “A winter climb can go well until folk get lost on the plateau.

“There can be slips, falls, poor navigation.

“But we are a young, fit team, with everyone well-trained and all pulling in the same direction.

“Afterwards everyone is tired with aches and pains and sore muscles, but we all share the same great feeling of satisfaction.

“Without our help, people are going to die.”

You might enjoy:

WATCH: Mountaineers wade through waist-deep snow to rescue stranded walkers in Cairngorms

Conversation