The deathly silence is unnerving.

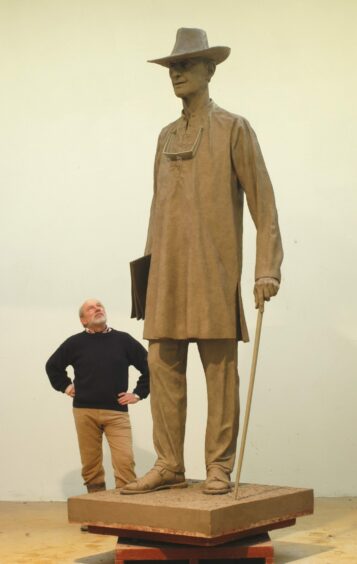

Sculptor Philip Jackson stands behind his clients, holding his breath.

He’s just put them in front of the statue they’ve commissioned for a first view, and he has no idea what their reaction will be.

He won’t know until they turn round.

It’s a ritual Inverness-born Jackson has been through countless times in his six decade long career, and it still sets his heart racing.

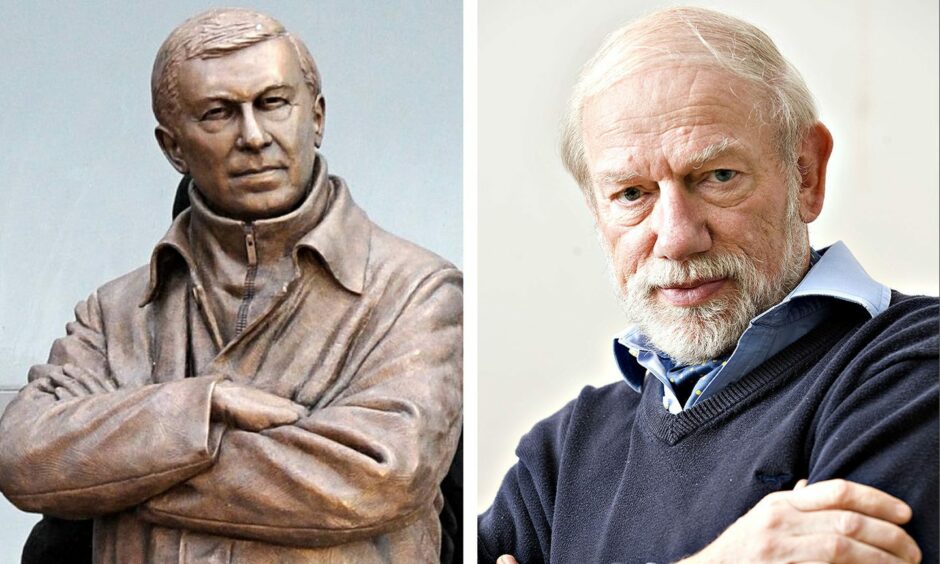

He’s made huge public sculptures of many well-known and much-loved people, from the late Queen Elizabeth to Sir Matt Busby and Sir Alex Ferguson.

In the case of the late Queen, protocol dictates that we shall never know what she thought of her statue in Great Windsor Park.

In the case of Matt Busby, the deathly silence was followed by a desperate hunt around the studio for the whereabouts of Sir Matt’s son, Sandy.

The sculpture was made only 18 months after his father died, and Sandy was eventually found in a different room, sobbing his eyes out.

Philip said: “Suddenly being faced with the figure of your father in a nine foot statue on a plinth, it’s an emotional moment.”

But for Philip, this was a good result.

He knew he’d managed to capture the likeness of someone no longer alive well enough to move his closest relative.

Creating a sculpture can be a long, challenging journey

It’s always a long journey, from the first approach of the client, to making and adjusting the detailed model of the piece, known as a maquette, to the casting of the massive piece in bronze.

Depending on the subject, it can also be quite angst-filled.

Patience, diplomacy and covert tactics are required when it comes to getting to know his subjects, especially royal ones.

A sculptor must know the measurements of his subjects inside out, but when it came to the late Queen, this proved rather delicate.

Philip had won a competition to make her statue for Windsor Great Park.

Queen Elizabeth was in her late ’70s at the time, and it was agreed that the statue would be of her on horseback, and as she looked in the middle of her reign.

Getting to grips with the Queenly measurements

Philip found the perfect photograph from the Royal Photographic Archives, and was invited to Windsor to watch the Queen riding around the indoor school while he took photos.

“I had far more sittings with the horse, it had less engagements than the Queen.

“Then I had the problem of finding out what the Queen’s measurements were.”

Philip was able to make contact with the Queen’s dresser, Angela Kelly, and was invited to meet her at Buckingham Palace.

Philip said: “I understand you can tell me how tall the Queen is, and she said, no I can’t.

“I said, what do you mean, you can’t tell me or you don’t know, and she said I can’t tell you.

“Then she crouched down and I said, are you telling me she’s this high?

“I got my tape measure and said OK, I make that so high, and she said, yes that’s right.

“There was obviously an embargo on people having the vital measurements of the Queen.”

It’s more than just height that’s required for a sculpture.

Further negotiations ensued, after which the Palace allowed Philip to make off with ‘Dolly’, a wooden mannequin made to the Queen’s measurements.

One highly delighted and relieved sculptor drove out of the Palace past the changing of the guard with Dolly in the back, an image which still makes him chuckle.

Fergie ‘a very interesting character’

Philip found Alex Ferguson ‘a very interesting character’, a great reader able to converse on all sorts of subjects.

“When he came to the studio he would say things like, just read a new book by Gore Vidal, it’s very good, you should read it, or have you read the new biography of Charles De Gaulle, it’s very interesting.

“When I went up to see him in Manchester he would walk around the training pitch singing, he was a great musician.

“It was obvious how highly he was respected by everyone.”

Philip decided he wanted to observe him during a match.

“I sat in front of him. His image during a match is of someone who’s concentrating, looking sort of angry, chewing gum, not the best look and not what I wanted to use for the sculpture.

“When I went to training ground and we walked round together, had lunch, I saw the real person, very co-operative and helpful.”

Philip is Inverness-born

For all that Philip was born in Inverness, there are none of his public sculptures in Scotland, and he’s only sculpted three Scots, Busby, Ferguson and Colin Tennant, Lord Glenconner.

Glenconner’s statue is on Mustique, the island he owned before his death in 2010, and Busby and Ferguson’s are at Old Trafford.

Scotland, like the US, has a preference for using local sculptors, and it seems to have forgotten the fact that Philip Jackson has Highland roots.

His mother was Invernessian Margaret Edwards.

Relatives at Culloden Moor

Philip believes she had a house at Culloden Moor, but that’s the extent of his knowledge of that side of his family.

His parents married during the war, and Philip was born in Inverness in 1944, spending his very early years in the Highlands.

“I left at an early age and hadn’t stored away those years, so there’s a vagueness,” he says.

“I love Scotland but have no relative that I know of still living there.”

Father interned in Africa during war

His father, Humphrey Hoskins Jackson flew in Bomber Command before volunteering for the Fleet Air Arm during the war.

He was shot down off the west coast of Africa and interned as a POW in Mali for the rest of the war.

Philip said: “He liked the place so he got a job in the Gold Coast, now Ghana, then went to Sierra Leone, then Gambia and retired to Tenerife, where he bought a house.”

Philip went to boarding school and spent time in Africa with his parents, and also with his grandmother and great-aunt on his father’s side.

He spent holidays with them in Surrey, and they proved a massive influence on him.

Discovering sculpture defined Philip’s life from an early age

“They were both elderly and they both had good libraries of books, and I spent a lot of time reading,” he says.

“Through them I discovered Greco-Roman sculpture at an early age, and I thought it was the most extraordinary thing that these wonderful figurative sculptures had been done by the hand of man.”

Aged 11, Philip bought his first book, a second-hand tome on sculpture, and it was to define the rest of his life.

“In it there were sculptures done by people that were still alive. The penny dropped that this wonderful thing called sculpture was still being done. I decided I really wanted to do this.”

Philip experimented with carving and modelling in clay until it was time to try and get into the local art school.

Art School unimpressed by him

The principal at Farnham art school was unimpressed by the young Jackson as he was self-taught to that point.

Enter the redoubtable great-aunt Evelyn Jackson.

She had been matron of Fulham Hospital during World War One wasn’t about to take no for an answer.

So Jackson was admitted to art school, and found himself at the start of what was to be a six decade long road, paved with grit, persistence, determination and strategic thinking.

An expensive career path

Whereas for a relatively small investment, painters can create a number of works and tout them about to get a foothold in the market, sculpture is an expensive business.

That’s where Philip’s strategic thinking came in.

He used his interest in photography to get a job with a press agency.

That’s where Philip’s strategic thinking came in.

He used his interest in photography to get a job with a press agency.

“On one occasion I did a photographic article about a company in Farnham that was doing a lot of large architectural contracts in the Middle and Far East and Africa, things going into large buildings effectively because of oil money.

“If you ever need a sculptor, I’m your man.”

“When I had done the article I asked them if they ever needed a sculptor, and they said, well actually we do, so I said, I’m your man.”

Philip joined the company and stayed there 14 years, ending up as MD.

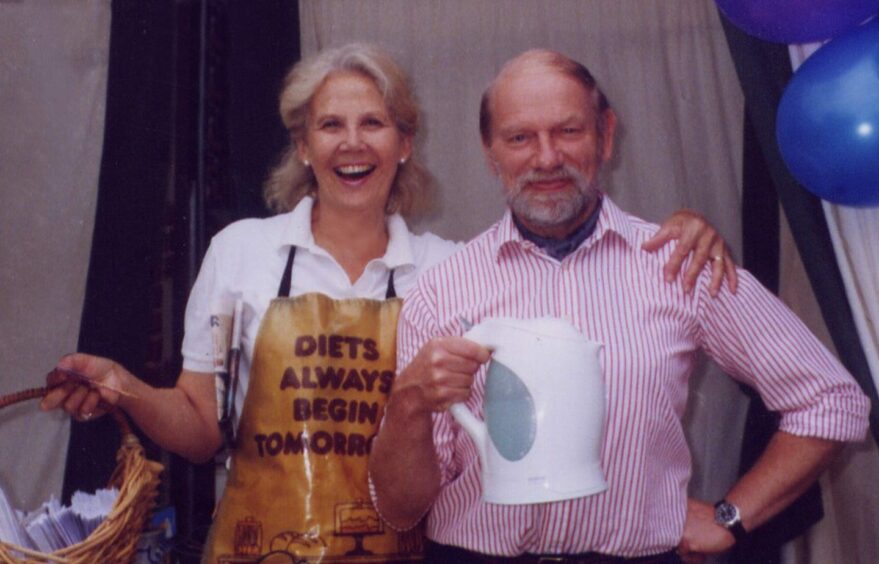

He and his wife Jean then decided to set up their own studio, and after winning a competition to do a sculpture in Manchester, things took off.

It’s a family business with Jean heavily involved in the administration of the studio, as well as being the person he trusts most to critique his work.

Their son Jamie is hands-on, checking the castings, checking the sculpture is put together the right way, patinating the small sculptures —”he’s intrinsic to the studio,” says Philip.

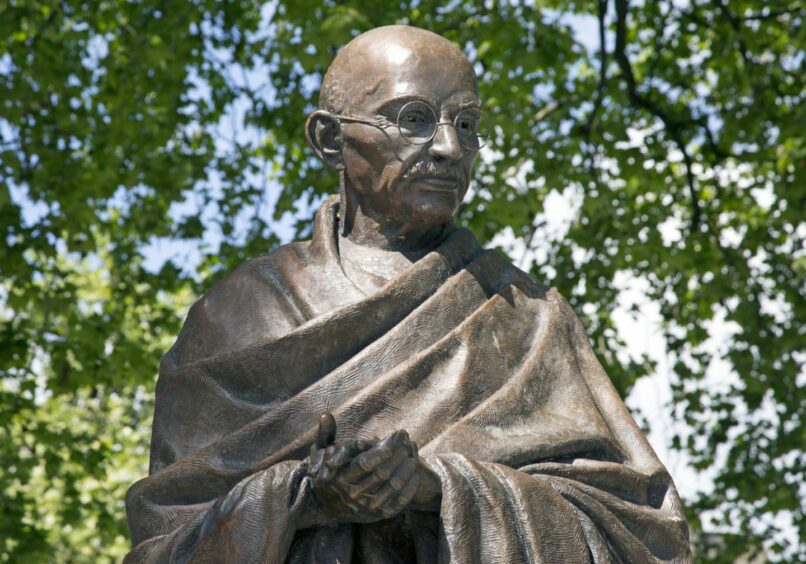

Since 1988 Philip has created around forty public sculptures, many of them military in theme, others of musicians, actors, footballers, religious icons.

In recognition, he was appointed Commander of the Royal Victorian Order in 2009, and has a fistful of other awards and honours.