Criminal exploitation is an increasing avenue for organised crime gangs (OCGs) to force their victims into in Scotland, including Aberdeen, Inverness, Tayside and Fife.

Everything from drug trafficking to shoplifting is a market for criminals where they think there is money to be made.

Drugs continues to be the most predominant market for criminal exploitation, both the selling and movement of substances.

Caught in a trap

The cannabis farm industry is exploding in Scotland with officers uncovering new locations nearly every single day.

Tayside investigators confirmed they are becoming an issue in the area as Detective Superintendent Fil Capaldi, head of the National Human Trafficking Unit, explains: “They’re lucrative, there’s lots of money to be made.”

The setup of such money-making operations makes them rife for abuse and exploitation with OCGs able to move their victims from farm to farm.

Traffickers pray on a victim’s desperation and a desire for a better life to coerce them into working the illegal industry.

Gangs smuggle victims in from countries like Vietnam and the person is in a debt bond to the traffickers or loan sharks.

Victims’ families will have mortgaged property to send them abroad.

Upon arrival in Scotland they are taken to cannabis farms and told they will be paid to look after plants.

As soon as they accept work from the OCG they are caught in a cycle.

DS Capaldi said: “He or she will do whatever it takes in order for that money to go back to their country of origin – and the OCGs know that.

“On the one hand you’ve got family expecting you to step up and respond to the money they’ve paid out and on the other hand you’ve got the OCGs looking to recycle you as often as they can.”

During a cannabis farm bust this April, which must remain unidentified due to legal proceedings, a victim was recovered who had previously been working on a farm in England but was unable to escape the cycle.

“His primary focus was to earn money and return it to his family,” said DS Capaldi.

“And he also owns a debt bond to the OCG who are helping him out by doing this for him.

“So it’s a vicious, vicious circle.”

Cases like that referenced by DS Capaldi have been witnessed across Scotland.

Kimi Jolly, founder of the East and Southeast Asian Scotland (ESAS) charity, says her organisation is aware of many cases like Ngo’s where victims have been criminalised.

The human rights advocate believes the criminalisation of victims caught up in these illegal industries is a problem in both the UK and Vietnam.

“What a lot of these smugglers do, they are very clever, they don’t do these things (work in cannabis farms) themselves,” Kimi explained.

“They usually identify a strong character that is also easy to manipulate and they get them to head these operations.

“They are not actually traffickers, they are one of the people that are being trafficked.

“A lot of the time they will ask young men to do it.

“They give them supervisory roles in the cannabis farms.”

This setup by the OCGs allows them to maintain a distance from the running of the cannabis farms for whenever police raids may occur.

“The actual bosses don’t live there” , said Kimi, “they live in their cushty houses wherever it is.

“A lot of the time the people who will get arrested are themselves victims because they have been manipulated into doing this work.”

Low risk, high reward

Criminal enterprises treat human trafficking and modern slavery as a lucrative arm of their often sprawling business model.

For hardened crime bosses, human exploitation is a low risk, high reward sector of their operation.

DS Capaldi explained that OCGs are always looking to diversify their interests in the pursuit of money.

“The same people who are involved in smuggling drugs across Europe, smuggling guns, involved in counterfeit goods, involved in small boats bringing migrants to the UK are the same people that are involved in human trafficking and modern slavery,” he said.

“Where there’s money you’ll find organised crime at its roots.”

The investigator claimed it was impossible to put a figure on how much money was changing hands but that the sums were vast, with recent operations recovering as much as £500,000.

“Substantial sums of money is an easy estimate but being able to put a figure on that is a hard one,” he said.

“We are aware of some of the groups that we’re looking at right now… there’s a lot of money changing hands.”

Globally human trafficking is thought to be a multi-billion dollar industry.

County Lines

One of the most prevalent forms of criminal exploitation detected around Inverness and Aberdeen is county lines drug running.

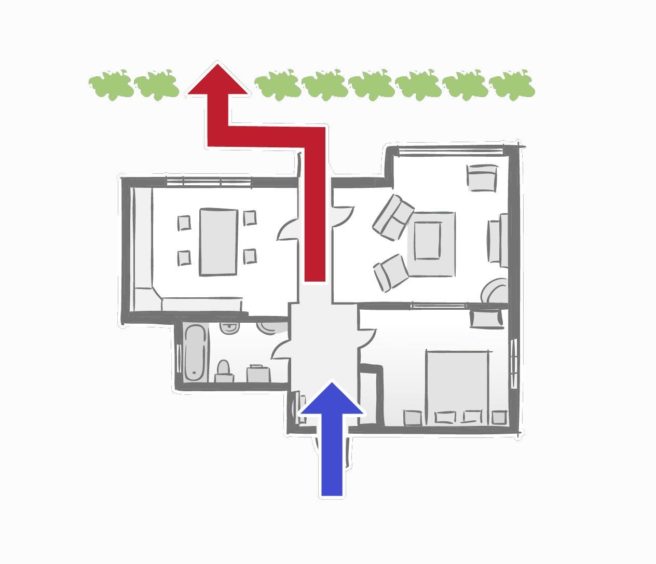

The county lines setup involves a network where gangs exploit the vulnerable and coerce them into trafficking drugs from large urban settings, usually cities, across borders and local authority boundaries to rural locations.

In Inverness and the north-east the majority of victims are male British teenagers, often as young as 15, recruited in London and forced to supply the markets north of the border.

Human trafficking officers are discovering that teenage boys are being shipped up to the Inverness area from English cities on a regular basis to feed the drugs market in the Highlands.

A worrying development in the county lines trade around Inverness is the appearance of vulnerable victims from Dundee beginning to show up in the city to move drugs.

Detective Inspector Calum Smith, Highlands and Islands division, believes this could be evidence of London gangs with connections in Tayside recruiting Dundee youngsters into their system and pushing them further north.

He said: “The assessment is that they are being recruited by some of these gangs from London and are then being sub-recruited and making their way to Inverness.”

DS Capaldi backed up his colleague’s assessment of the prolific nature of the drug trafficking networks operating in the regions.

“What we’re finding in the North, North-East is county lines.

“Drug gangs moving people south of the border and bringing them up there,” he said.

Drugs bust uncovers county lines child trafficker

October 1, 2018. Davidson Drive, Aberdeen.

A 25-year-old man bolts for the back entrance of a house on the residential street in the Northfield area of the city as police burst through the front door on a drugs raid.

He escapes through the kitchen and into the neighbour’s gardens but is later hunted down and arrested.

Officers find 102 packages of heroin and cocaine and two wraps of crack cocaine hidden in a bag after searching the property. The haul is worth nearly £16,000.

Investigators also discover weighing scales with traces of drugs and £3,385 in cash – the majority of the money locked away in a safe.

The arrested man is Glodi Wabelua.

Unknown to officers, they have just caught the ring leader of an evil county lines child trafficking gang who would soon become the star of a landmark human trafficking case in London.

Wabelua along with fellow gang leaders Dean Alford and Michael Karemera, all 25, ran a lucrative drugs supply line into Portsmouth from London using teenagers as young as 14 as their mules.

The gang’s operation was simple, horrendous and effective.

The three ringleaders were in charge of telephone lines that drug users in Portsmouth would call to buy Class A narcotics.

Each line had its own brand or tag name to ensure users knew who the message was from – even if the number had changed.

The gang exploited at least five young teenagers and a vulnerable 19-year-old to carry out their county lines network.

The victims, all from south London, were recruited and groomed before being sent to Portsmouth where they were harboured in drugs users’ homes and waited to carry out the gang’s instructions.

This practice of taking over drug users’ or other vulnerable adults’ homes is known as cuckooing – named after the bird which uses other birds’ nests for its young.

Wabelua, Alford and Karemera had total control over their teenage victims’ travel and freedom of movement.

When the gang received a supply of Class A drugs, the three ringleaders would send text messages to Portsmouth customers using their individual brand lines to let them know drugs were available.

Users would then call back to place an order. Each of the three lines were receiving around 200-300 calls a day.

The gang leaders would then send text messages to their victims already holed up in Portsmouth and instruct them on where to sell and drop off the drugs.

After selling the drugs, the victims would deposit the takings – which could be as much as £2,000 a day.

The ringleaders would frequently meet the victims at night to re-supply the drug lines to sell on the streets of Portsmouth.

The teenagers would be the ones forced to travel the 70-odd mile journey south from London to Porstmouth with the drugs, putting themselves at risk.

Vicious cycle

The overwhelming majority of victims being exploited by county lines gangs are born and raised in the UK and could help explain the growing statistics for underage youths believed to be potential victims of criminal exploitation.

Often they come from troubled backgrounds which makes them easy targets for criminals.

In a vicious cycle, similar to that seen in sex trafficking, the exploited youths can become the exploiter as they get older.

The system becomes a process of victims working their way up the chain by identifying potential mules younger than themselves that they can push.

Across the UK in 2020, there were 1,544 victims of exploitation flagged as county lines cases – of this total, a staggering 1,371 were under the age of 18.

Jaydon Hall: Criminal, victim or both?

An example of the often blurred lines between criminals and victims in county lines investigations is the case of Jaydon Hall.

At the beginning of April 2020, Hall and a 17-year-old accomplice who cannot be named for legal reasons, were sent to Dundee by English gangsters to sell crack cocaine in the city.

Upon arrival in Dundee, the teenage duo took over a property on Baxter Street belonging to Nicola Walker.

From the Baxter Street home and a second address on Abbotsford Place the pair quickly began dealing.

Using cuckooing methods of intimidation, Hall and his accomplice forced Ms Walker to live in her bedroom as they took over the living room and sold crack from the windows.

Then things turned violent. A £1,000 stash of drug money went missing from the bathroom.

On April 23, while her friend Andrew Cusick was visiting her home, Walker admitted to her two captors that she had taken the money.

In a furious rage, the 17-year-old grabbed a kitchen knife and stabbed Mr Cusick on his arm with such force that the blade protruded out the other side.

As Walker and Cusack tried to escape, Hall grabbed the woman and repeatedly punched and slapped her on the face until she was left bleeding.

On October 27, both Hall and his accomplice were each sentenced to 24 months in custody.

However, despite the vicious nature of their crimes, it was recognised in court that both were also victims of modern slavery.

Sentencing the pair at Dundee Sherriff Court, Sherriff Tom Hughes said: “You appear to have undertaken your criminal activities at the behest of others in England, who are no doubt gaining huge financial profit from the evil that they spread from their havens down south.

“It is sad to say that you appear to be victims of these evil criminals. They are using you.

“I take into account that you have been assessed as being victims of modern slavery yourselves.

“What is clear is that you made a positive decision to become involved in this illegal practice.”

This investigation understands that Hall is no longer in prison.

Justine Currell, director at modern slavery charity Unseen, believes OCGs have become more reliant on criminal exploitation in Scotland amidst the Covid-19 pandemic.

“For Scotland the biggest type of cases are related to labour but that’s closely followed by criminal exploitation and that’s what we’ve seen throughout probably the last 9 – 12 months,” she said.

“A decline in labour, even though it’s still the most prevalent across the UK, but an increase in cases involving criminal exploitation and sexual exploitation – and that’s really concerning.”

The charity’s modern slavery and exploitation helpline recorded an 88% rise in contacts from victims forced into criminal exploitation in Scotland in 2020.

Unseen’s work has uncovered cases of modern slavery across the local authorities in Scotland.

Worryingly, from 2017 when the data begins, Perth and Kinross features heavily – with around 80 potential victims of modern slavery discovered in the region.

Aberdeenshire, Angus, Fife, Dundee and the Highlands all recorded at least five cases each within that time.

‘Very adept criminals’

Justine, who co-authored Unseen’s annual report into the crisis, says criminal gangs are “adept” at moving from one market to another.

She said: “It’s not unheard of for gangs to move people around into different areas, into different types of exploitation, to just continue making as much money as possible.

“We’re normally talking about very adept criminals who can move their, for all intents and purposes, business operations.

“There are also gangs that will pass potential victims from one to another and they’re not exclusive by any stretch of the imagination in terms of types of exploitation.

“We do see that kind of read across in terms of different typologies.”

In addition to the prevalent drug market, Unseen has also seen cases of forced begging, forced shoplifting and sex for rent.

“It can be any criminal act really,” explained the charity director.

“Someone is forced to undertake a criminal act that they wouldn’t normally do for fear of threat or violence.”

Are you a victim of human trafficking or modern slavery in Scotland? Have you witnessed it in your area? Call the Modern Slavery Helpline on 08000 121 700. Or call Police Scotland on 101 or 999 in an emergency.

If you would like to speak to our Impact investigations team please email Dale.Haslam@ajl.co.uk

The Exploited

The Exploited is a special investigation exposing the hidden prevalence of human trafficking and modern slavery in our local communities. Across rural Perthshire and the Highlands to urban Aberdeen and Dundee – victims, and their abusers – are hiding in plain sight.

Read the full series:

- Young mother raped daily in Perth flat after being trafficked across Europe

- Trafficked women brought to Aberdeen and sold online for sex

- Fears Vietnamese trafficking gangs will bring crystal meth labs to north and north-east

- Man injured after being forced to work at Aberdeen construction site with no pay

Credits

- Words by Sean O’Neil

- Design by Cheryl Livingstone

- Illustrations and graphics by Roddie Reid

- Data visualisations by Lesley-Anne Kelly

- Videos and photography by Drew Farrell, Steve Brown and Blair Dingwall