There is nothing quite like a sense of hope in some future event to make you feel alive: the fevered rush of anticipation; the secret optimism of the unknown outcome.

This month’s Oscars will have all the superficial glamour that Hollywood does best: the Dior gowns skimming hour-glass figures, the sparkle of Cartier diamonds on lily-stem necks, the wanton march of fame on the plush red carpet. What gets swept under that carpet is the messier stuff of human emotion. Ambition. Fear. Ego. Self-belief and self-loathing. Ironic that façade, given it’s the authenticity of human emotion on the big screen that is up for judgement.

Amongst the big-hitter nominations, like A Star is Born, are more niche additions.

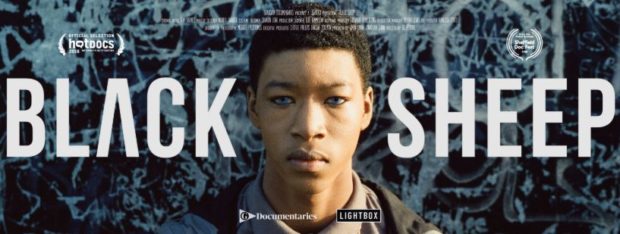

Black Sheep is a documentary about racism in Essex, consisting almost entirely of a young black man talking direct to camera about his experiences. Cornelius Walker describes the day Damilola Taylor died in London. He was 10, the same age as Damilola, and felt bewildered watching his mother cry. They didn’t know the Taylor family. “It could have been one of you,” his mother sobbed.

Shortly after, they moved out of multi-cultural London to Essex. Determined to protect her boys, his mother unknowingly moved them to an all-white, hostile environment.

Taunted and beaten for being black, Cornelius responded the only way he knew how: by conforming. He bought the same clothes as his attackers, bleached his black skin, put blue contact lenses in his dark eyes – and joined in their violence. He bought a new image and in the process, sold his soul.

Crucially, he suppressed his real feelings. I watched Cornelius’s mesmerising account with growing fascination as an array of complex emotions flitted across his face and through his eyes. Then I discovered that it wasn’t Cornelius at all. It was an actor playing Cornelius. In an era of “Towie”, we confuse fact and fiction regularly and for a moment, I felt cheated. Later, I realised it didn’t matter. The artifice gave me something real: sadness, anger, a new depth of empathy and understanding.

That same day, I read about another Oscar-nominated film which focuses on the two child killers of toddler Jamie Bulger. Jamie’s parents were outraged by its inclusion, saying it was too sympathetic. Nobody would want to criticise a family who has undergone their trauma. It is understandable that they don’t want to examine or understand why Thomson and Venables behaved as they did. But the rest of us have to.

Whatever they turned out to be as adults, it was tragic that two 10-year olds lived a life in which inflicting pain and suffering was an acceptable option. To simply demonise them as “monsters” meant we didn’t have to examine ourselves. A broken child has broken adults surrounding them.

Sometimes, optimism gets dashed, just as it will on Oscar night. When my daughter was small, she used to love lucky bags from a high street accessories shop. You never knew what it contained: a sparkly trinket, a nail varnish, a hair ribbon. Once, we opened one and found boxes. But disappointment replaced anticipation. All of them were empty. In the disappointed silence, we looked at each other and laughed. So much promise. So little delivery. “We’ll fill them,” I said, “give them substance.”

Our society seems full of empty boxes right now. Apparent sophistication and no content.

In the same week that I watched Black Sheep, several other stories caught my eye. A white man who screamed and swore at Muslim schoolgirls in the street, suggesting they should be sterilised so that they didn’t “breed like rats”. A poll that suggested one in 20 didn’t believe the holocaust was real. (And 20% of French 18-34-year olds had never heard of it.) So much anger. So much ignorance.

The day I read the holocaust statistics, The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas was shown on television. It’s a controversial film, sometimes criticised for showing pain in the Nazi perpetrator’s family as well as Jewish families. But as well as understanding historical fact, we need to understand emotional truth. Why are we so much more comfortable with simplistic slogans than complex analysis? To understand is not to condone. To understand is to hold the power for change.

Our society is so full of hate at times, so lacking in sophistication. Legislation exists for all our “isms”: racism, sexism, anti-Semitism. But it’s easy to legislate against actions, harder to legislate against attitudes. Laws are just empty boxes that we need to fill with knowledge, education, and understanding.

Perhaps film is as good a place as any for that exploration. When the wine-stained Oscar gowns are in the cleaners, the Dior diamonds are back in the jewellers, and the cold light of day has dawned, there will be both disappointment and euphoria.

I just hope the gongs have gone to the films – whether fiction like A Star is Born or documentary like Black Sheep – that put some substance into society’s empty boxes and offer an emotional truth.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter