Once dubbed the picture-house capital of Scotland, Aberdeen was left with only three cinemas after the closure of the Grand Central and Queen’s cinemas 40 years ago today.

During cinema’s silent film heyday, Aberdeen had 17 cinemas – six of those were on Union Street alone.

But by the 1980s, the video rental market proved to be the death knell for an already declining industry.

Herbert Donald, director of Aberdeen Cinemas Limited, said “the changing pattern of entertainment meant the cinemas were no longer viable”.

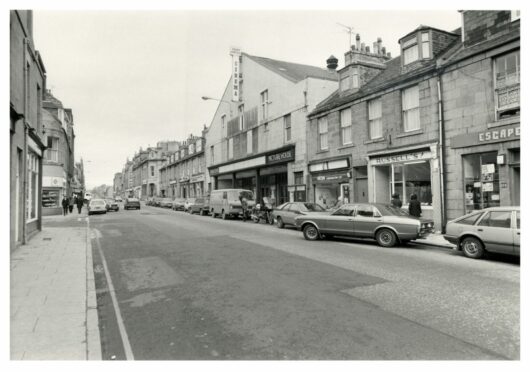

He made the decision to close the Grand Central on George Street and the Queen’s Cinema on Union Street citing “crippling losses”.

It was a sad day when both cinemas showed their final films on October 17 1981.

Not least for some of the staff.

“I’ve been here so long I started to think the Grandy belonged to me”, said pensioner Helen Davidson, a cashier at the Grand Central for 12 years.

“All that time here – I don’t know what I’ll do now.”

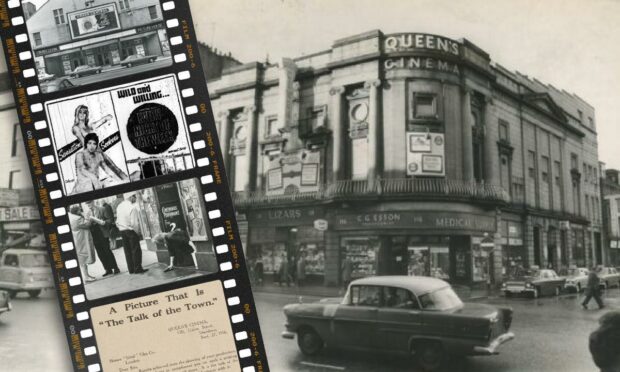

The Grand Central in the glory days

The Grand Central opened on April 3 1922 during the golden age of cinema as part of James Donald’s group of cinemas in Aberdeen.

Unlike other cinemas that opened in Aberdeen during that era, the Grand Central was a converted shop and more understated in appearance.

Located at 286 George Street, the cinema had been Allan’s Stores until it was transformed into a vast auditorium which seated 730 people.

It may have lacked the frills and flourishes of some of the city’s purpose-built cinemas, but it did have an accomplished four-piece orchestra – which at one point was lead by a woman, talented violinist Marjorie Littlejohn.

Business was booming, and Mr Donald acquired neighbouring properties with a view to expanding his cinema.

The makeover was planned for 1927, but delayed until 1929.

But it was worth waiting for. Press reports at the time said the reopening of the lavish Grand Central was “an illustrious page in the history of cinema entertainment in Aberdeen”.

After extensions and alternations, what was once a “suburban hall” had been transformed into Aberdeen’s biggest cinema.

The walls of the old building were torn down, the roof was raised and after just six weeks of closure, the new Grand Central arose from the granite rubble.

The new hall could seat 1020 patrons in the auditorium and a further 620 in the balcony – some 400 more people than other city cinemas.

Described as a “miraculous” timescale, it was reported that the plasterers and painters were still at work as Aberdonians queued down George Street for the opening screening.

The ceremony was attended by the city’s dignitaries – Mr Donald was himself a councillor – and he promised to give “good value for money – that was what every Aberdonian wanted”.

The new, trippy decor sounded like it could have come straight from an Alice in Wonderland screening.

Leaving the bustle of George Street behind, viewers stepped into “a fairyland of waving trees, stately pillars and smiling skies of blue”.

Elsewhere there was vegetation – both real and painted – lighting, grand murals and decorative pillars.

A blue day for blue movie fans

The cinema underwent more modernisation in the 1950s when it was remodelled to house the latest technology – a Cinemascope screen.

The days of live music to accompany films were long gone and the auditorium was made much simpler, with most of the ornate decor removed and murals painted over.

Further modifications in the 1970s saw the exterior canopy altered, an illuminated sign installed and the acquisition of the closed city cinema’s old projectors.

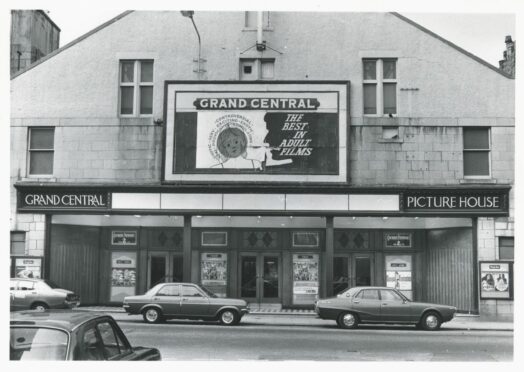

But by now, the cinema had firmly left any hint of whimsy and fairyland behind – it had become Aberdeen’s premier spot for ‘adult’ film showings.

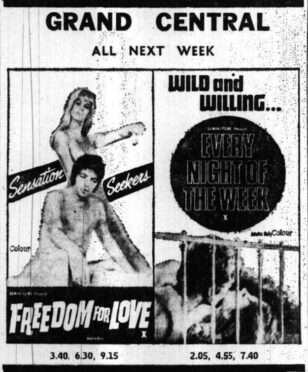

Billed as showing “the best in adult films”, it took on a raunchy reputation showing such flicks as ‘My Pleasure is my Business’ and ‘Freedom for Love’.

The Grandy was threatened with closure in summer 1981, not because of its seedy screenings, but because it didn’t meet new fire regulations.

It survived the threat but the cinema only limped on for another few months.

Takings at the box office were only about £1000 a week; £1500 short of the amount needed just to break even.

And in September 1981, owner Mr Donald announced he had made the difficult decision to close loss-making enterprises in the city.

He hoped to deploy most of the Grandy staff elsewhere in his entertainment empire, but cinema manager Tony Veal was to be made redundant.

Mr Veal was optimistic, and quipped: “It’s really the best thing that could have happened, I was getting in a rut and now I’m forced to look for another job.”

The Grandy’s final showings on October 17 1981 were a double bill of pornographic pictures, and attracted the best audience in months.

The lights dimmed for the last time with a strictly adult-only screening of ‘Love, Lust and Ecstasy’ and ‘More Danish Blue’.

Some customers said they were making a nostalgic trip back to a favourite haunt of their youth, others just wanted to be there as the curtain came down on a historic era in Aberdeen’s cinema history ahead of the building’s demolition.

After doing the usual check at the end of the night for lost property, Tony and his staff closed up for the final time and went to a nearby pub.

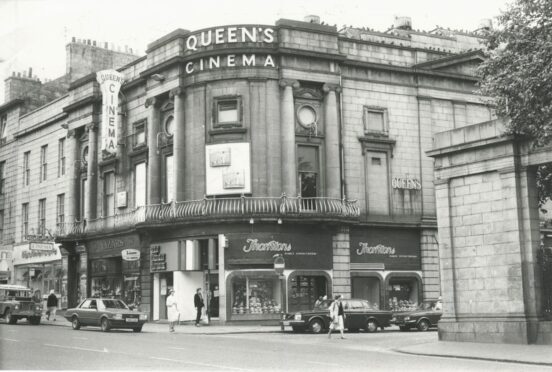

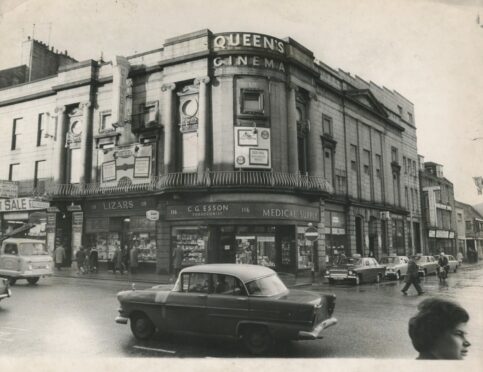

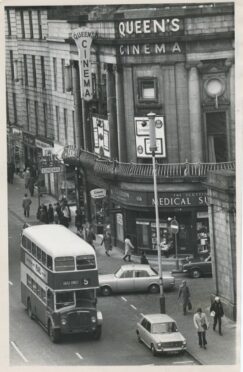

The Queen’s Cinema

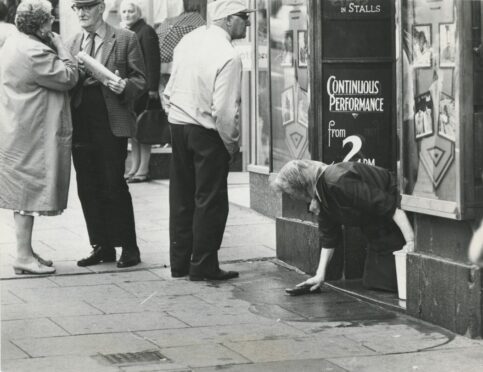

On the same night in 1981, the final curtain fell on the Queen’s Cinema on Union Street, however, its farewell was a much more regal affair, befitting its long history.

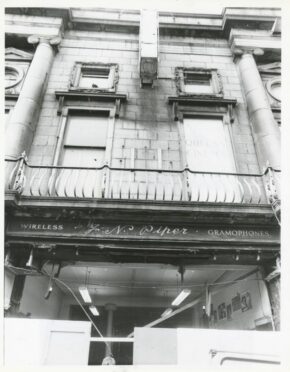

The Queen’s opened on Union Street on Hogmanay in 1912, but the grand building it was housed in was much older dating, back to 1837.

It was the former Advocates’ Library and Hall on the corner of Correction Wynd and 120 Union Street, before becoming the Conservative Club.

The upstairs rooms were renamed the Queen’s Rooms around the time of the Golden Jubilee in 1887, and the name stuck when the building became the elegant Queen’s Cinema and Tea Rooms.

The rooms were “sumptuously decorated” having been transformed by the Davidson Brothers cabinetmakers and D & J R McMillan architects.

The opening night was packed. A report on January 1 1913 described how films were played back to back from 7pm until after midnight.

The four screenings were “a delightful, coloured pantomime picture” called ‘Santa Claus and the Clubman’, a travel film ‘Conca D’Oro’, a romance ‘The New Clerk’, and a comedy called ‘The Swimming Party’.

The First World War was just around the corner, and the cinema regularly hosted war relief entertainment to raise funds for the war effort.

The Queen’s would be decorated in different themes; one evening in 1914 saw the interior hung with French tapestries to acknowledge the destruction of the cathedral in Reims in France.

A couple of decades later, the cinema itself was nearly destroyed after an extensive fire following a fusebox failure.

All of Aberdeen’s firefighters battled for two hours in June 1936 to save the building which was well ablaze.

The Queen’s was almost completely destroyed inside, with parts of the roof caving in – a scene that drew hundreds of spectators on Union Street.

The smoke was so thick that it blew down the Denburn Valley into the railway station making visibility tricky for train drivers.

But despite the danger above, the shops below the cinema remained open and customers simply used umbrellas inside to avoid being drenched by the water pouring through the ceiling.

The end of the Queen’s reign

The cinema was renovated in the fashionable Art Deco style and reopened the following year showing ‘Rainbow on the River’.

The interior was completely remodelled with the screen moved to the Union Street side of the cinema, and the seating provision was increased from 430 to 550 with the addition of a balcony.

A sophisticated ‘mirrophonic’ branded sound system was installed – the first of its kind north of Glasgow – making the Queen’s the most up-to-date cinema in Aberdeen.

The building was B-listed in 1967 in recognition of its “distinctive curved corner bay with dominant Ionic pilasters” forming an important part of the city centre streetscape.

But even architectural prowess and up-to-date equipment couldn’t save the cinema from the future of home entertainment.

Along with the Grandy it was earmarked for closure in September 1981 when it was making a loss of £800 a week.

The owners said the Queen’s could not compete with “the biggest threat of all to the ailing industry – the video”.

A brand new shop in Aberdeen called Video Shuttle was luring the public away from cinemas renting out films for £1.15 a night, far cheaper than the price of a cinema ticket.

Three city pubs – the Castle Inn, the Three Lums and Fusion – had also started showing films meaning punters could watch a movie for the price of a pint.

The grand old dame of Union Street’s reign was coming to an end.

It’s final showing, the perhaps apt melancholic movie ‘Watership Down’, aired on October 17 1981.

The closures meant the Donald family’s cinema empire had dwindled to one venue – The Capitol – from the 12 they had owned during the golden age of the silver screen.

It was truly the end of an era for chief projectionist George Milne who showed the final film – the first ever film he saw from the project box was at the reopening of the Queen’s in 1937.

The manager Jack Douglas and his staff marked the sad occasion in style with drinks and cigars to toast the cinema’s final curtain call.

Former Queen’s projectionist Frank Craig returned for the final night along with his one-time apprentice Peter Donald.

Although sad, Mr Craig lamented that times had changed and that “the cinemas had been running at a loss just to give cinemas to the cinemagoers”.

If you liked this, you might enjoy: