As Aberdeen merchant John Thomas Morton watched his provisions business grow to become an enormous canning enterprise in London, he could never have dreamt it would spawn one of the most famous – or perhaps infamous?- clubs in English football.

It would also become one of the outlets for the numberless animal war heroes of the north-east — the sheep, pigs and cattle put into tins to be shipped off to feed the armed forces in the First World War.

Tins of Morton products would also end up feeding the Shackleton and Scott Polar expeditions.

And Morton’s Millwall factory was the scene of feisty strikes by women and suffragettes standing up for their conditions and against child labour.

Clayhills factory in Aberdeen

J T Morton was born in London’s Oxford Street in 1830.

When he was 19, he established a small factory at Clayhills, Aberdeen, producing preserved and canned foods mainly for export.

The business took off to the extent that Morton had established a base in London by 1851 and by 1858 had a head office and factory in Leadenhall Street in the city, conveniently close to Smithfield meat market.

Six years later, he opened a new cannery and processing plant in Millwall, and this too rapidly expanded to cover an enormous site in an area known as Sufferance Wharf.

Meanwhile, in Aberdeen the Clayhills site relocated to a new factory on Mount Street in Rosemount.

Morton’s range of products grew from canned fish and meat to include soup, vegetables, fruit, sausages, ham, bacon, cheese, confectionery, jams, jellies, marmalades, candied peel, pickles, sauces, potted meats, and potted fish, oatmeal, barley, spices, pepper, salt, curry powders, bottled essence, tea, cocoa, flour, nuts, custard powder and hair oils.

Early beginnings of Millwall FC and its Aberdeen players

In 1885 Morton’s Millwall workers, including a number of Scots from Aberdeen and the north-east, formed a football team from the casual germ of a team known as Iona, wearing blue and white.

It wasn’t completely founded by the Scots as legend sometimes has it, explains Jim Murray in his book Millwall: Lions of the South: “A group of workers in a preserve factory – many of them Scottish, some English – were convinced they could form a football team to give other local clubs a tough time.

“A Scottish flavour certainly, reflected in their choice of colours for the kit of navy blue and white.

“The names of some of players in Millwall first season show the cosmopolitan mix that was the Isle of Dogs in those days.

“Duncan Hean (Capt) George Oliver, J Reekie, Patrick Holohan, Owen Elias, Henry Gunn, Tom Jessup, Joe Potter, Fred Northwood, John Rowland, James Crawford, Harry Butler & George Syme.

“The club secretary was 17-year-old Jasper Sexton, the son of the landlord of the Islander pub in Tooke Street where Millwall Rovers held their meetings.”

Duncan Hean was from Dundee and the Honorary Secretary was one William Henderson, thought to be a Scot and Morton employee.

First chairman a Highlander

The first chairman of the club was Highlander William Murray Leslie, son of Alexander Leslie, a farmer at Knockbain by Munlochy in the Black Isle, and Isabella Murray, hence Murray Leslie.

They were both born in Aberdeenshire but Murray Leslie himself was a Black Isle lad, born in 1859 and living in 1871 in Wester Suddie Farm, now known as Roskill.

He became a surgeon’s assistant in Bolton, Lancashire, and went on with his brothers to own property in the City, and practices in the West End, Grosvenor Street and Westminster.

Legend has it that between 1911 and 1915 he and his wife Margaret were living at Boleskine House on the shores of Loch Ness, owned until 1913 by the infamous Aleister Crowley, one of his patients.

Any thought that the Millwall club badge is derived from the Scottish Lion Rampant is also nonsense, according to the Millwall History Files.

“Millwall were known as the Dockers until around the turn of the century when things African came into vogue due to the Boer war.

“With Millwall’s cup run to the semi-finals in 1900, they were referred to as Lions for their acts of giant killing and the name stuck and was adopted as the club’s nickname and emblem.

“It did not appear on club shirts as a badge till the 1930s.

“The first Millwall emblem in the ‘We Fear No Foe’ badge bears no resemblance to the heraldic Scottish lion used by the Scottish FA, indeed even the current badge bears only a passing resemblance to it.”

In a quirk of history, Millwall has never played against Aberdeen.

J T Morton may not have thought much of the rise of the club, however.

Devout

He was known to be a devout Presbyterian, somewhat reserved and distant, but considered to be fair and honest.

He died enormously wealthy in 1897, giving more than half his wealth away to churches and charities.

The business went to his two sons, Charles Douglas, and Edward Donald, but their father wouldn’t allow them to trade under his name, so in due course the firm became C & E Morton.

The brothers proved shrew businessmen themselves, increasing sales by establishing agents overseas, and travelling the world to grow their trade.

The Boer War had a silver lining for C &E Morton when the company supplied food to the military; and the First World War had a positively golden lining as the firm became principal suppliers to the British Army.

Aberdeenshire historian Colin Johnston has studied the use of animals in the First Word War.

He said: “Perhaps the greatest contributors in warfare were the humble horses, cattle, pigs and sheep of Buchan.

“Countless thousands, millions, of these creatures supplied food for the men in the trenches and at sea, not to mention boots, belts, sheepskin jackets, saddles, leather strappings, parts of uniforms and so on.

“C & E Morton and canners A & J Maconochie of Fraserburgh were iconic and prodigious providers of food rations for Britain’s armed forces, especially in WW1.”

Trinity Cemetery memorial

A memorial was put up at the site of the Rosemount factory commemorating workers from C & E Morton who fought and died in the First World War.

In 1938 this was moved to the Trinity Cemetery to make way for the Rosemount municipal housing development.

During the First World War, the company continued to pay half-wages to its staff serving in the armed forces.

Shortly before the outbreak of the war, C& E Morton was listed as a public company valued at £650,000, almost £95 million in today’s money, with premises not just in London and Aberdeen, but also in Mevagissey, Polruan and West Looe in Cornwall.

Industrial unrest at C & E Morton

Mortons had its fair share of industrial unrest in the early 20th Century, witnessed in a newspaper account of conditions for more than 1000 women who went on strike for better pay in March 1914:

“Some of the women strikers are more than 50 years old, and have worked there for 20 or so years.

“In the busy season, which lasts four to six weeks, they work from six in the morning till nine or so at night.

“Their work is to cut up rabbits, which come in already frozen, and then are kept in water for one day, after which they are put up in tins by girls and then taken to the tinsmiths.

Dirty, dull work

“The rabbits are cooked in the tins, and are then packed in large boxes by the men.

“Puddings, mince-meat and cod-roe are all prepared and packed up by the women.

“The work is very hard, very dirty work and is very dull.”

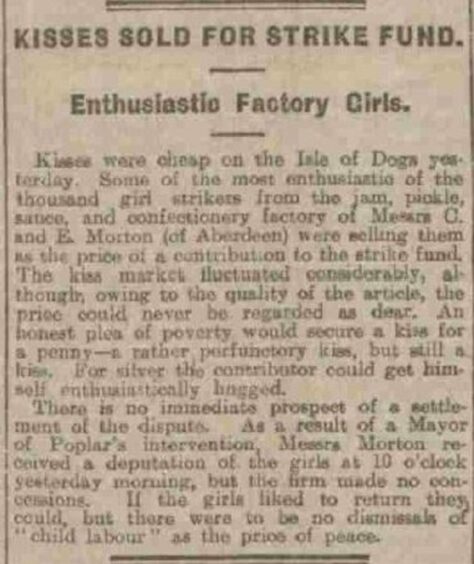

The girls resorted to selling kisses to raise money for the strike fund.

The Evening Express reported: “The kiss market fluctuated considerably, although owing to the quality of the article could never be regarded as dear.”

Even someone pleading poverty could get a kiss, albeit perfunctory, for one penny, while for silver “the contributor could get himself enthusiastically hugged”.

Beginning of the end

After the war Mortons lost ground to foreign and colonial competitors and had to turn to the home market.

In 1945 the company was taken over by the Beecham Group and the Morton business was concentrated at Lowestoft, producing canned vegetables and fruit fillings.

The Millwall works were gradually run down.

Conversation