It is a story of survival and the strength of the human spirit, even in the most harrowing of circumstances.

And the fashion in which John Mennie transcended the privations of life in a series of Japanese prison camps during the Second World War by recording what he witnessed with all the skill he could muster highlighted the fact that art can thrive in adversity.

Mr Mennie, who was known to family and friends as Jack, was born in 1911 at Springbank Place in Aberdeen and trained at the city’s Gray’s School of Art, as the prelude to advancing to the Westminster School of Art in London.

Yet, in common with so many other people of his generation, he recognised that his personal goals and ambitions had to take second place to serving his country once the hostilities commenced between the Allies and Germany and Japan.

He joined the Royal Artillery in 1940 and was posted in September 1941 to Singapore, but was one of the thousands of Scottish troops who found themselves massively outnumbered and in dire straits in conditions which far suited the enemy.

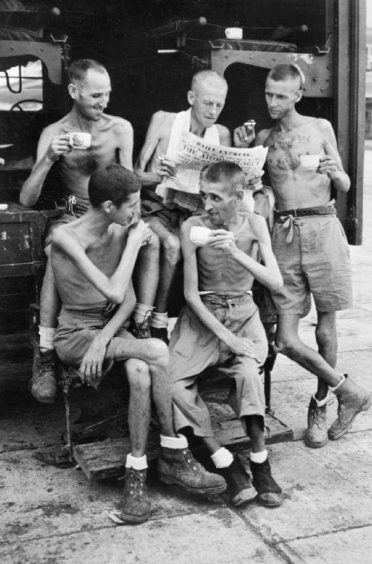

He and many of his colleagues were captured when Singapore surrendered to the Japanese forces in February 1942 and he was a prisoner of war until August 1945.

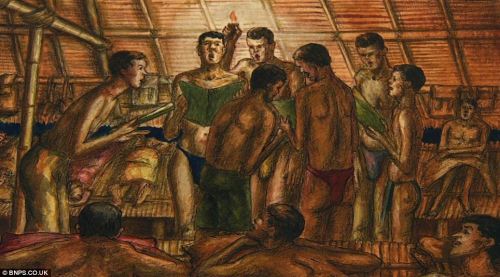

He saw the worst of human behaviour, but also depicted the comradeship which can thrive when strangers are flung together and recognise the value of common purpose, even as friends and colleagues are dying around them.

The north-east man produced a substantial trove during his time as a prisoner of war with more than 50 pieces of work subsequently archived at the Imperial War Museum in London.

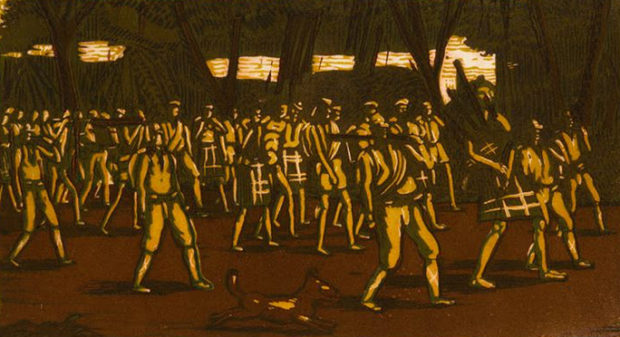

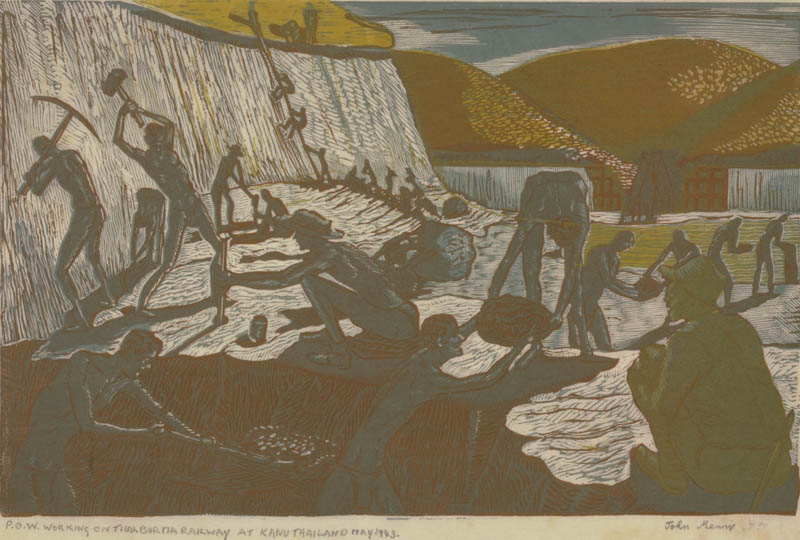

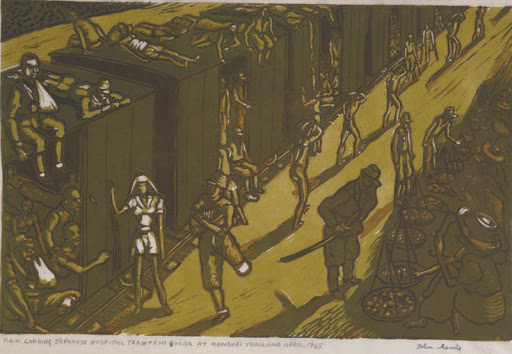

Mr Mennie’s prints were made from lino-cuts of the same size and copied from original drawings in the camps.

These were produced on odd bits of paper such as cigarette packets, blank flyleaves found in books and even paper rifle practice targets.

His evocative works came to fruition in the POW camps in Changi, Singapore, in 1942, Kanu in 1943, Chungtai and Tamawau in 1944 and Pratchi in Thailand in 1945.

For eight years before the war, he had been working as a commercial artist in London and all his prison-camp confreres helped him by contributing to his meagre stock of materials – pencils, paper and even a Chinese box of child’s watercolour paints came his way and he deployed all these to the best of his abilities.

As a non-smoker, Mr Mennie secured a precious addition to his equipment by bartering 10 cigarettes for a tiny quill brush as part of his kit.

It was typical of his resilience and commitment to making the best of the horrific conditions which were prevalent when he and thousands of other Scots were herded from camp to camp by adversaries who made no effort to adhere to the tenets of the Geneva Convention which was supposed to safeguard prisoners of war.

His nephew, Alex Gordon, who lives in Elgin, has worked hard to ensure his uncle’s unique paintings are being shown to a wider audience across the world.

He said: “The Japanese never gave their captives any clothes and they went from the clothes in which they were captured in 1942 to almost complete nudity in 1945.

“After the (Death) Railway was finished in 1943-44, they used POWs as a labour corps to the Japanese Army and sent them from the camps for various tasks.

“One such camp was an ammunition depot which was near the structure made famous in the film Bridge over the River Kwai.

“These sites were bombed regularly by the RAF, so the Japanese decided to move the ammunition further east.

“And the trains were loaded by POWs to accelerate this task.”

Some of their journeys were the stuff of nightmares.

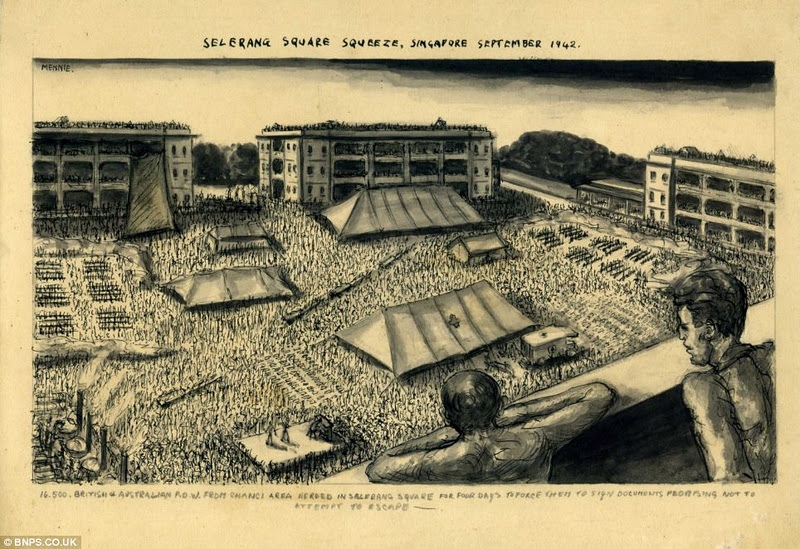

Large numbers of prisoners were moved from Changi to Siam, which was a gruelling trek of five days and four nights.

The men were packed into trucks, eight feet wide by 20 feet long – and there were 30 men in one of these vehicles.

The horror of that experience is vividly evoked in one of Mr Mennie’s documentary drawings which shows the miserable, bedraggled mass of humanity crammed like sardines onto the floor of the lorry.

Nor was there any respite once they finally limped off the truck.

That was followed by a six-day trip up river on a flimsy barge to Kanu, a mere clearing in the jungle, which had to be transformed into a camp by the prisoners themselves.

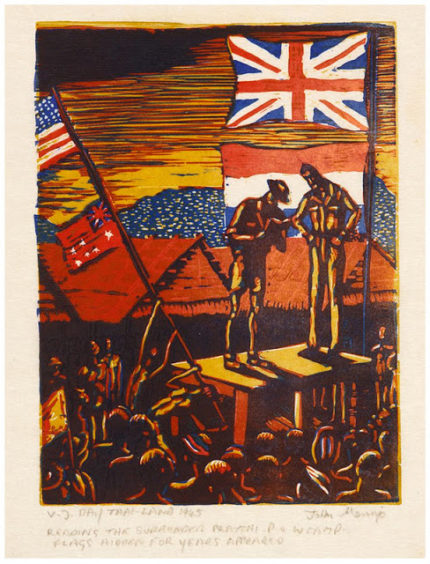

When the war ended in 1945, Mr Mennie was working on building fortifications in the east of Thailand at Pratchi.

He managed to keep his drawings hidden throughout the conflict, but near the end of the hostilities, the Kempi Police who had a habit of searching from time to time found them and confiscated them, but did not destroy them.

When the POWs came home, they signed a undertaking to the government that they would not talk about the war crimes they had witnessed. But at least, they were safe.

Understandably, Mr Mennie’s experiences attracted plenty of attention when he returned to his native land and attempted to resume his art career.

The Aberdeen Journal was among the publications which carried extensive coverage of the many travails and distressing experiences which the Scot had endured throughout his long period of captivity.

But it also focused on his ingenuity, his never-say-die philosophy and unstinting determination to use whatever resources he could find to create an archive of the graphic scenes which he witnessed at first hand amidst his incarceration.

The report stated: “Drawings which might have cost him his life or stung his Japanese guards into brutal reprisals, were safely concealed for over three years by an Aberdeen man during his ordeal of captivity in the Far East.

”They constitute a unique record of the heroism and the horror of life for British prisoners of war captured at the fall of Singapore and forced to work on the notorious Burma-Siam railway.

”Triumphing over disease and semi-starvation, Lance/Brigadier John Mennie gradually became a man with a mission – to bring back faithful pictorial evidence of what all the prisoners went through.“

The Journal detailed the secretive and often hazardous measures which he employed even as his weight diminished and he was at increasing risk from illness.

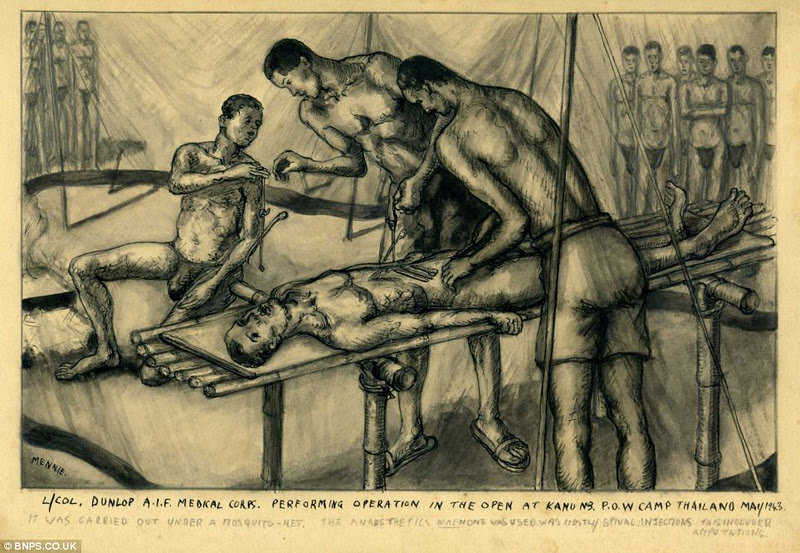

It added: “L/Bdr Mennie did two sets of drawings: a documentary series exposing Japanese barbarity and the conditions endured by our POWs and a set of 80 sketch portraits of prison camp comrades.

”The first set, with its damning indictment (of war crimes) was kept in the hollow stem of a bamboo walking stuck and it was never discovered by the enemy.

”The portrait series he kept under a piece of three-ply wood which was used as a rest fir his mess tin and, although the Japanese stripped his bed and searched his kit on three occasions, they left the drawings undisturbed.

”Thinking the Japanese would regard them as harmless, Mennie fashioned a little portfolio to hold these portraits and it was this, with its contents, which was seized following a kit inspection in January 1945.

“The enemy declared they would ‘censor’ the portraits and laid them aside in the camp office to be dealt with later. Before leaving the camp, however, Mennie managed to communicate with a comrade who was staying behind.

”He told him where the drawings were and asked him to keep a look out and, if the opportunity arose, he should recover them.

”It was more a counsel of hope than conviction. But, just a little over a year later, all the 80 drawings were safely returned – through the post to the author’s home in Aberdeen.”

Mr Mennie rarely spoke about his memories of the camps after he had returned home to Blighty.

In common with so many of his generation, he had no wish to inflict his own grief and angst on his family and friends.

However, unlike the majority of other soldiers, he had created a body of work which told its own story about his experiences, whether watching painfully thin soldiers singing Christmas carols together or seeing a colleague undergo a surgical procedure.

He subsequently became a successful artist and spent most of the rest of his life in London, where he met his wife Dorothy. She also painted and the duo were never happier than when they were bringing their imaginations to bear on a canvas.

Eventually, while the couple were on holiday in Scotland in 1982, Mr Mennie died at Tirinie amid the picturesque setting of Blair Atholl.

There were no grand tributes at that stage and it has only happened gradually that people have grown to realise the unfettered courage and conviction with which Mr Mennie poured his heart into his art.

As Mr Gordon said: “The emotional pride and love we have for our Uncle Jack is difficult to put into words.

“It is entirely impossible for us to understand the hardship, filth and deprivation he and his fellow POWs had to endure for three and a half years, and manage to survive.

“We are very fortunate that he had the drive, skill and astounding bravery to produce these wonderful art works which could easily have cost him his life.

“Without the artists who risked punishment and indeed life to record forever the brutality and living conditions, people at home would not have known the full awfulness of life in a Japanese Prisoner of War camp.”

He has left behind a legacy which ensures his name will never be forgotten.

And that will be especially true when the nation stops to remember the countless soldiers who were wounded, killed or imprisoned during the fighting in the Far East before VJ Day was finally celebrated in August 1945.