Researchers have revealed that Scotland’s largest Pictish settlement was in Aberdeenshire: a discovery that “shakes the narrative” of the UK’s medieval history.

A bustling community of 4,000 people are once thought to have called Tap O’Noth, a hill near Rhynie, home.

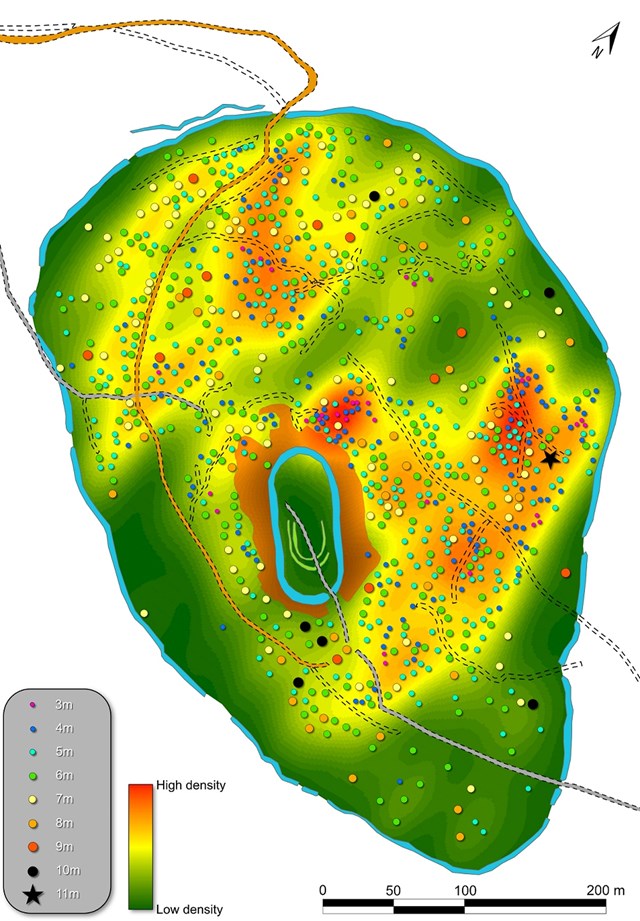

A total of 800 huts were strewn over the hilltop and now “stunned” archaeologists have found that they in fact date back to the Pictish times.

Radiocarbon dating suggests the hill’s fort was constructed in the fifth to sixth centuries AD and that the settlement itself may date back as far as the third century AD.

Previously, archaeologists assumed the settlement dated back to the later Bronze or Iron age.

Professor Gordon Noble, who led the research, said: “This makes it bigger than anything we know from early medieval Britain.

“What was previously thought to be the biggest fort in early medieval Scotland is Burghead, at about five and a half hectares (13 acres).

“In England, famous post-Roman sites such as Cadbury Castle and Tintagel were around seven hectares (17 acres) and five hectares (12 acres) respectively.

“The Tap O’ Noth discovery shakes the narrative of this whole time period.

“If each of the huts we identified had four or five people living in them, then that means there was a population of upwards of 4,000 people living on the hill.

“That’s verging on urban in scale and in a Pictish context we have nothing else that compares to this.”

Drone surveys also found one “notably larger hut”, which indicates that Tap O’Noth had its own form of hierarchical organisation within the fort.

Prof Noble added: “We had previously assumed that you would need to get to around the 12th century in Scotland before settlements started to reach this size.

“We obviously need to do more to try and date more of the hut platforms given there are hundreds of them, but potentially we have a huge regional settlement with activity emerging in the Late Roman Iron Age and extending to the sixth century.

“It is truly mind blowing and demonstrates just how much we still have to learn about settlement around the time the early kingdoms of Pictland were being consolidated.”

Archaeologists from the university have conducted extensive fieldwork in the surrounding area since 2011, but had previously focused on the lower valley rather than the hilltop.

At a settlement in the valley, they have previously discovered evidence of the drinking of Mediterranean wine, the use of glass vessels from western France and intensive metalwork production, all of which suggests it was a high-status site – and possibly one with royal connections.

Bruce Mann, archaeologist for Aberdeenshire Council said: “In the early centuries AD there were widespread small communities scattered across the landscape.

“These then largely disappear during the time of the Roman campaigns and we’ve struggled to understand what happened.

“Perhaps now we have evidence of people coming together in large concentrations at a handful of places, a reaction to the threat of external invasions.”