It was the street of tears.

The immense slaughter of World War One took an extremely heavy toll on one specific street – Aberdeen’s Great Northern Road.

A chilling total of 106 men from this roughly two-mile long street were killed during the conflict – a forgotten chapter in the city’s history.

The concentration of fallen heroes came to light during our investigation to honour soldiers from the north-east as the nation pauses for Remembrance Day.

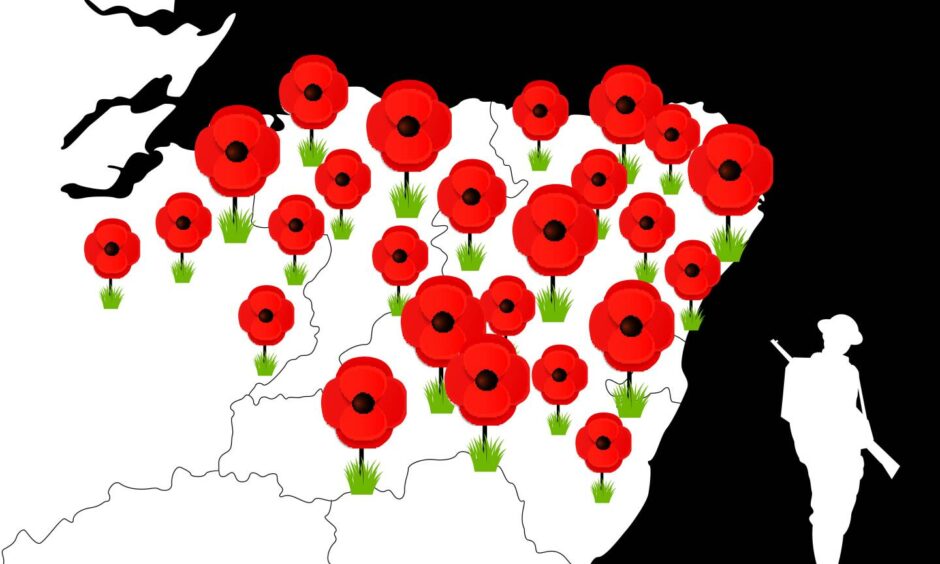

Our interactive map shows a sea of red poppies marking the fallen in and around the historic thoroughfare.

One of Scotland’s leading historians Professor Emeritus Sir Tom Devine of the University of Edinburgh, said the street was an emotive symbol of the nation’s trauma.

‘Hugely important we remember the sacrifices’

Sir Tom, who also taught at Aberdeen University, said: “There was a heavy haemorrhaging of young men at the local level. The kind of losses seen in the Great Northern Road were not untypical.

“There was an extreme localism in recruitment with units recruiting from specific areas – such as the Gordon Highlanders in the north-east.

“Scottish soldiers were used as shock troops in many Western Front operations. It is hugely important we remember the sacrifices made.

“Many of the losses were young men aged between 17 and their early 20s. It was a slaughter of the innocents.

“We can see even in the signage of war memorials, the sheer scale, brutality and enormous loss of the Great War.”

A combination of patriotism, peer pressure and socio-economic factors meant that few families on Great Northern Road would have been untouched by the horror of the trenches.

Phil Astley, city archivist for the Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire Archives, said: “At the time of the First World War, Great Northern Road would have been a solidly working class area with a fairly young demographic.

“Those that signed up from this area would have been more likely to have been in the infantry and hence on the front line of the conflict.

“Given the young demographic of the area, it would also have been true that if one brother in a family enlisted then his siblings and friends would have been under a bit of pressure to follow suit.”

The shockwaves of war

When war erupted in 1914, Aberdeen men and women eagerly answered the call to arms. The city played a key role in the deployment of troops to northern Europe and also supplied vital munitions.

Thousands responded keenly to recruitment drives, and soldiers were billeted in the city before being sent off to fight the enemy overseas.

The city also played a vital role in caring for the many wounded soldiers who returned from the Front. The effect of the war on Aberdeen was huge.

Historian Derek Tait, author of Aberdeen in the Great War, said that by the end of the conflict, there wasn’t a family in Aberdeen who hadn’t lost a son, father, nephew, uncle or brother. The shockwaves of the war would blight the city for years to come.

He said: “So many people from the same area died because the population density would have been higher in those streets.

“Also, many would have been friends and worked together and probably joined the regiments together.

“Great Northern Road was quite a long road so would have had a higher population of young men.”

He added: “Conditions in the trenches would have been appalling. At times, the soldiers would have been knee deep in mud with, during battle, their comrades dead or dying around them.

“It would have been a grim existence and the fear must have been dreadful. Many would have been very young, just in their teens. Some under-age boys lied about their age to join up. When the war first started, many joined up because they saw it as an adventure, for a skirmish they thought would soon be over. Even politicians probably didn’t think that it would drag on so long.”

Dyce Work Camp

Despite the rise in patriotism and public pressure to sign up for service, some were keen to oppose the slaughter of the war. Conscientious objectors were opposed to bearing arms and serving in the military.

Dyce Work Camp, north west of Aberdeen, was set up in August 1916 to house conscientious objectors who had been in prison for refusing military service in the war.

These men had been released on condition that they performed “work of national importance” – breaking up granite to produce stone for road building.

Conditions were poor – one man died of pneumonia.