I vividly remember the Home Office promotional video.

They introduced their settled status system to the world between Christmas and New Year 2018, the perfect time to bury controversial news.

The film was a snazzy, upbeat affair with sliding images of delighted, diverse, young and attractive people having the time of their lives.

These, however, were juxtaposed with sentences which landed like a killer blow for me and those like me: “EU citizens and their families will need to apply to the EU Settlement Scheme to continue living in the UK after December 31 2020.”

It wasn’t the content of the video – to be honest, I had expected some sort of registration process. No, it was the tone: blithe and shallow, dismissive of the concerns and worries of the the three million and more EU-born residents of the UK.

The debate is personal for me

As I write, we are in the last week of June – a week that marks both the fifth anniversary of the Brexit referendum and the final deadline for applications to the government’s EU Settlement Scheme. It is also publication week for Scottish by Inclination, my book celebrating the contribution of EU citizens living in Scotland.

As an EU-born immigrant to Scotland, this debate is personal for me and for many I care about. And yet we seem to be almost invisible in public discourse.

Take the travel restrictions debate, for example. How many times have you heard the “when will I be able to get a holiday in the sun?” sentiment this month alone?

Now put yourself in my shoes: my 84-year-old mother lives alone on the continent and I have not been able to see her. The cost of quarantine and testing is prohibitive, and even if I could go, Germany has closed its door to the UK due to the Delta variant.

We need to name the plight of international families, not just bewail the trials of the travel industry.

Brexit fatigue is leading to indifference

I understand Brexit fatigue, believe you me. Of course, we would rather not dwell on things that are now inevitable, especially with the pressing issues of the pandemic and the daunting challenge of the climate emergency. But let’s not brush what remains of our crumbling European stars under the carpet quite so readily.

“I’m sick of hearing about Brexit,” say many and proceed to the football scores.

In the aftermath of the referendum half a decade ago, the same indifference was palpable in the words of several acquaintances: “We don’t mean you. Not people like you. It’s not personal.”

I’m not going to settle for those comments, as indifferent and superficial as the Home Office advert.

The expensive farce of gaining citizenship

As a European-born Scot of 30 years’ residence, I admit to feeling a little rankled that I had to apply for permission to stay with my Scottish husband and my three Scottish-born kids. But, like a good girl, I complied, hovering my passport over my mobile phone on the kitchen table in the hope that the app would work, and the document would scan. Surely this would be the end of it.

Not quite. Having secured settled status, I was made aware that, as with many European countries, dual nationality with my homeland Germany would cease to be an option after the final Brexit deadline.

How random some of the questions in the Life in the UK test are. Would you know the year in which Charles I was executed? Or how many people sit on the jury of a youth court in England?

I counted my pennies and decided to take the leap into full citizenship. A friend who had trodden this path before me said: “Good call. The only way anything is guaranteed is if you have citizenship.”

With the cliff edge of December 31 approaching, I had one shot at this application. One.

Digging deep, I handed over £1349.20 to the Home Office – the standard fee for a citizenship application – plus hundreds of pounds of lawyer’s fees, plus fees for biometric appointments, plus charges to take the Life in the UK Test, plus return fares to Glasgow from the Highlands for several Home Office appointments.

I got busy revising, too. How random some of the questions in the Life in the UK test are. Would you know the year in which Charles I was executed? Or how many people sit on the jury of a youth court in England? Or the century in which Christianity first appeared in the UK? Or where the National Horse Racing Museum is?

Meanwhile, I also hunted down deleted emails for exact dates of every time I had travelled abroad in the previous decade. I scanned every payslip from 2011 onwards in support of my application, for goodness’ sake. It was madness.

Belonging is a choice

When I complained about this in a tweet, a huddle of helpful Brexiteers pointed out (in words I won’t quote here) that I should have applied for citizenship much sooner. They were missing the point: I simply had no need to.

Until December 31 of last year, this was my territory already – we were all part of the European Union. Even without the financial barriers, the level of hassle was prohibitive, all for a British nationality I didn’t really need.

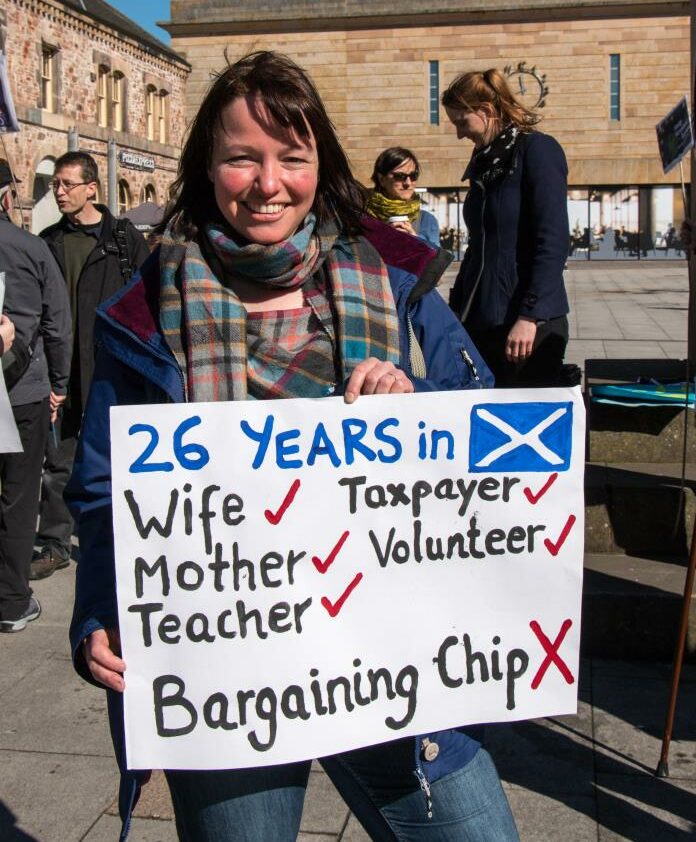

Identity is a strange concept, isn’t it? I am a mother, a wife, a teacher, a taxpayer – and a children’s writer. My novels are set in Scotland, concern themselves with Scottish history and the Scottish landscape and are widely studied in Scottish schools. Shouldn’t there be a disclaimer somewhere? “This author isn’t Scottish, just so you know”?

Whatever the answer, the truth is that my life turned on a hinge when, at 4:40am on June 24 2016, a tired-looking David Dimbleby announced on the BBC: “The British people have spoken, and their answer is: we’re out.”

If I have learned anything over the five years since that moment, it is this: belonging is not a privilege. Belonging is a choice. Long before I received the official Home Office document, I resolved to be Scottish by inclination. I have chosen to belong.

And you know what? I’ll settle for that.

Barbara Henderson is a children’s author and columnist