I heard that Mischa is dead now, but when we met many years ago, I was struck by her exaggerated femininity.

Or what some people class as femininity. An extravagant flirtatiousness; a dramatic use of sweeping eyelashes.

Mischa started out life as a man and had been through so much to transition in the early days of surgery. The external presentation of her gender was not important compared to her internal certainty of what that gender was, of who SHE was.

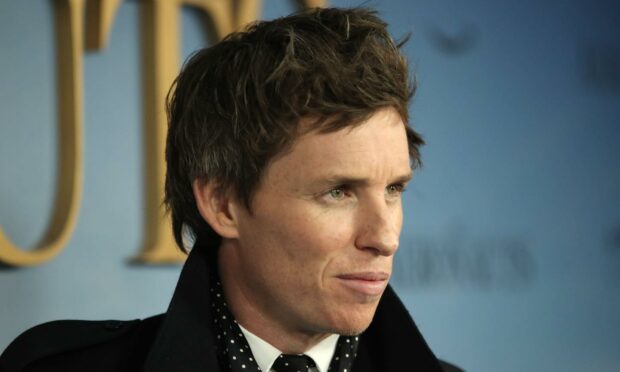

Eddie Redmayne’s much-publicised interview this week, in which he said it was “a mistake” to play the part of trans pioneer, Lili Elbe, in the 2016 film The Danish Girl was confusing. Lili, like Mischa, had gender reassignment surgery. What was “mistaken” about Redmayne playing her? His performance? He was nominated for an Oscar, for heaven’s sake.

Eddie Redmayne’s much-publicised interview this week, in which he said it was “a mistake” to play the part of trans pioneer, Lili Elbe, in the 2016 film The Danish Girl was confusing. Lili, like Mischa, had gender reassignment surgery. What was “mistaken” about Redmayne playing her? His performance? He was nominated for an Oscar, for heaven’s sake.

Now, personally, I did not find Redmayne completely convincing. It felt like a man’s observation of what it is to be a woman: an overplayed coquettishness; an overly self-conscious delicacy. Then I remembered Mischa. In any case, it wasn’t the quality of his performance that Redmayne regretted. It was his gender status. Apparently the role should have gone to a trans actor.

Well, silly me. All these years, I have been labouring under the misapprehension that, as an actor, you pretend to be something you are not. That’s your skill. That’s your art. You convince me that your fiction is part of my reality. Are we saying that to act in Casualty, it’s necessary to have worked in A&E? Or to play a cop in The Bill, you need to have served in the Met?

Actors and writers use experience as a springboard

After meeting Mischa and some of her friends, I was so moved by their stories that I felt compelled to write a novel about love and gender. There was nothing effete about the process of their transition. It held pain and trauma and turmoil, both physical and emotional, and you needed a steel core to survive it. I wanted to capture that reality.

The question is not whether Redmayne is transgender, but whether he can effectively convince you that he is

It’s what writers – and actors – DO. They use their experience as a springboard for their imagination and offer you a simulated reality. Should I not have written because I only researched and am not, myself, transgender? What great swathes of literature would be erased if that were a creative commandment. Thou shalt only write what thou hast personally experienced?

My objection to Redmayne’s implied reduction of imagination to the feet of experience does not spring from lack of empathy, but from an objection to creativity being submerged in rigid sociological theories that have becomes as much of a straight-jacket as the ignorance and prejudice they replaced. Art is not the arena for that. The question is not whether Redmayne is transgender, but whether he can effectively convince you that he is.

Real empathy matters

As both Mischa and Redmayne proved to me in their presentations of femininity, we all have different ideas of what it is to be male or female. The transgender debate is supposedly about tolerance, about the fluidity of human sexuality, but there doesn’t seem to be much tolerance about how we discuss those issues. The death threats to JK Rowling, and the revelation that Australian actor Hugh Sheridan received so much abuse for playing a trans role that he attempted suicide, illustrate just how toxic this debate has become.

Is it not odd that there are so many vociferous voices commenting on the representation of trans characters in the fictional world, when there are still so many human rights abuses of women in the real one? Of course, the protection of one set of rights does not exclude the existence of another. Yet, it does seem like there’s a fashion to these issues that currently shows more interest in defending the right to CHANGE gender than defending the right to be BE a particular gender.

This week, I read about the struggles of women in Turkey against domestic abuse; the struggles of women in Afghanistan who are being denied education; the struggles of women in China – including tennis player Peng Shuai – speaking out in the Me Too movement. But the most depressing story of the week surely has to be the election of a child rapist to be mayor of a South African town. It is in these stories that the world reveals its true moral compass in its attitude to gender.

All those years ago, Mischa had to fight against prejudice for understanding. Now – quite rightly – there is more support for the trans community. But real empathy matters, not needless pontificating. Perhaps if we approach gender issues with true integrity in the real world, the fictional one will take care of itself.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter