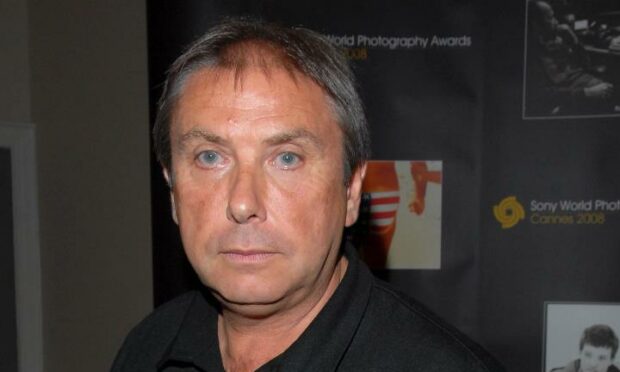

The death was reported last month of an important figure in international journalism, who was probably unknown to many. Tom Stoddart from Morpeth in Northumbria, died of cancer at the age of 67, having survived numerous war zones and disaster areas.

He had wanted to be a reporter, but when he applied for a job at the Berwick Advertiser, the only position available was as an apprentice photographer.

He was to go on to have an outstanding career in photo-journalism. His images were published in prestigious of titles around the globe. Many carried fulsome obituaries in recent weeks.

The Toronto Globe and Mail’s explained: “From the battlefields of Bosnia and Iraq to the crumbling Berlin Wall, he spent four decades chronicling a world of conflict and change.”

Tom Stoddart portrayed ‘the fury of war’

The Washington Post ‘s tribute was headed “British photojournalist who portrayed human dignity amid the fury of war.”

The Times recalled “In April 1987, Tom Stoddart and the Sunday Times journalist Marie Colvin travelled to war-ravaged Lebanon in search of the kidnapped Church of England envoy Terry Waite. Though they did not find him they managed to bribe a Shia militia commander to allow them into a besieged Palestinian refugee camp. The pair were afforded a 60-second window of opportunity to make a run for the camp without being shot at.”

In an interview carried by the Newcastle Chronicle in 2019, Tom Stoddart spoke of the camp. “The conditions were terrible. People were eating rats and being shot and killed on a daily basis.”

Marie Colvin, who was to be killed in 2012 covering the horror of Syria, smuggled rolls of his film out in her underwear on their hazardous return. The photos made front pages. They contributed to the camp being liberated within days, the Red Cross moving in and evacuating the injured.

Marie Colvin, who was to be killed in 2012 covering the horror of Syria, smuggled rolls of his film out in her underwear on their hazardous return. The photos made front pages. They contributed to the camp being liberated within days, the Red Cross moving in and evacuating the injured.

The Guardian recalled that Stoddart did not like colour photography, regularly quoting the Canadian photographer Ted Grant saying: “If you photograph in colour, you see the colour of their clothes, but if you photograph in black and white, you see the colour of their soul.”

Photography had a global impact

Seeing in black and white the desperation in people’ s eyes amidst the human carnage of the break-up of Yugoslavia, for example, one could understand Stoddart’s preference. He was in Sarajevo in 1992 to show the world the human cost of the siege of the city imposed by Bosnian Serb forces, the longest siege in modern history. His photography again had global impact.

Later that year he returned to the city and was injured during a bombardment. He was evacuated and spent a year recovering, but went back in 1993 to document the hardship of life in Sarajevo in the bitter winter. He later said he was drawn to that conflict because of the “dignified and resolute way that these people conducted themselves.”

That people like Tom Stoddart, Marie Colvin and others have been willing to risk their lives to bear witness to what men with guns can do, has meant the rest of us can’t claim we never knew. They have been a breed apart.

Journalists are a breed apart

So too it would seem are another group of journalists, those who cover the royal family. They have been the subject of a two-part BBC documentary, the Princes and the Press. It examined the “complicated” relationship, official and unofficial, between royal reporters and princes William and Harry. The tabloids, the ‘serious’ papers and magazines were represented.

A former private eye who claimed to have worked for the News of the World, told of phone hacking and surveillance of a former girlfriend of Harry’s. The Royal Correspondent of the Times talked about his exclusive on royal aides complaining of Meghan’s bullying.

Tom touched the lives of so many as a brilliant, compassionate, courageous photographer whose legacy of work will continue to open the eyes for generations. He gave voice to those who did not have one and shone a light where there had been darkness. pic.twitter.com/rJ3LZTv0E5

— Tom Stoddart (@Stoddart_Photos) November 17, 2021

The palace (the collective term for the royals and their teams of advisers), was reportedly furious about the documentary, and in particular the suggestion there had been a briefing war between William and Harry.

But if the programmes left us wondering about what the princes are really like, Rachel Cooke, the New Statesman’s estimable TV reviewer left her readers in no doubt about the journalists featured: “If Harry at moments comes over like a spoilt brat, he’s still more sinned against than sinning. Some of the parasitical gargoyles on parade here only make their weird, royal semi-necrophilia seem all the more repellent by talking so very earnestly about it, as if they were reporting not the activities of a highly peculiar family, but Watergate or the My Lai massacre.”

The world they inhabit, is certainly far removed from Tom Stoddart’s.

David Ross is a veteran Highland journalist and author of an acclaimed book about his three decades of reporting on the region