The eyes of the world have been focused on America this week following the worst outbreak of race warfare since the 1960s.

There have been riots and protests from demonstrators with President Trump threatening to send in the US military to restore law and order.

George Floyd

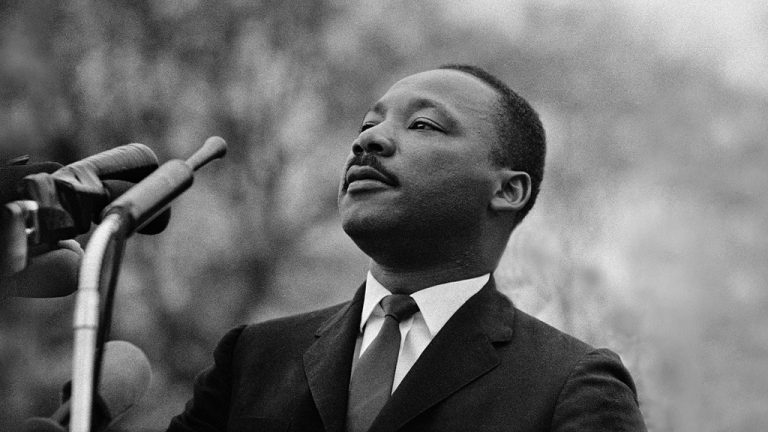

The trouble, sparked by the killing of black man George Floyd, has continued for more than a week and shows little sign of dissipating; a world removed from the scenes which surrounded the funeral of Dr Martin Luther King on April 9 1968.

That sad occasion brought together men and women from every background and race.

And north-east teacher Alan Small was among the mass gathering of mourners in Atlanta and kept a poignant diary of his recollections which he later handed to his family before his death in 2012.

Mr Small, who was a youth worker at St Katherine’s Club and Community Centre – which is now The Lemon Tree – in the early 1960s was a teacher at the city’s Summerhill School.

But he spent a year in Atlanta with his family and watched the American news programmes with a mixture of horror and sadness after the assassination of Dr King.

Momentous events

Indeed, he was so moved by the tragedy that he made a recording of the momentous events and the tape of his experiences has been transcribed by his son, Chris.

Mr Small recalled: “First, there was a private service in Ebenezer Baptist Church where Martin Luther King served as co-pastor.

“We decided we would watch the service on television and join the march afterwards.

“The service was extremely moving.

“It was the first funeral of a black person to be nationally televised and was attended by so many national figures.

“These included Robert Kennedy, Jacqueline Kennedy, vice-president Hubert Humphrey and (later president) Richard Nixon.

“By the time we got to our spot, overlooking the street in front of the state capital, there was a powerful air of expectancy and a good deal of police, with TV cameras set up at vantage points and helicopters overhead.

“Nobody was quite sure what was going to happen.

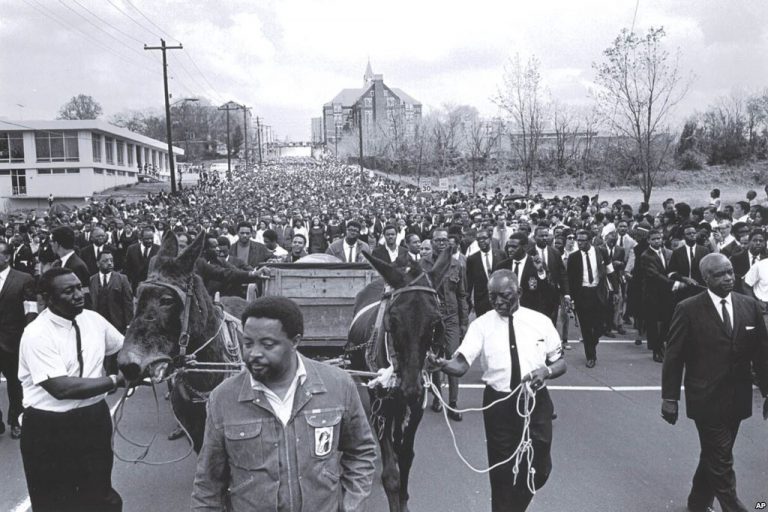

“Then, over the brow of a hill, to our right, half a mile away, we gradually heard the noise of the march which was preceded by the coffin containing Dr King’s body.

“I will never forget the visual impact of the scene as a mass of people – the number was variously estimated as anything from 75,000 to 150,000 – came over the hill towards us abc the streets were jammed solid.

“I had my camera with me. But somehow, when the coffin drew level with us, I felt that I was too emotionally involved and that taking photographs would have been completely inappropriate.

“I was involved, I was committed and I became a participant in it. I would not need a photo or a colour slide to remind me of the scene.

“Having let most of the immediate march go past, we simply left our place on the sidewalk and joined them.

“The three or four short steps from the pavement to the march appeared to me to be an act of commitment.

“As long as you were on the sidewalk, you could act as if you were an onlooker watching the action, but not involved in it either physically or emotionally.

“But as soon as you were part of the march, you were identified with it.

“For me, it meant emotionally and I hope, at an intellectual level too, a commitment to the causes which he lived and died for.”

In the midst of the procession, Mr Small was impressed by the lack of pomp which surrounded it.

Stage and screen

Many stars from Hollywood and Broadway were in attendance, but there was no standing on ceremony.

He added: “The Southern Christian Leadership Conference had decided that, in order to convey an impression of the causes dear to Martin Luther King, his coffin should be carried in an old four-wheeled wooden farm cart which should be drawn by two farm mules.

“The symbolism of this is that the mule is the means of power used by the poorest sharecropper, by which he hauls all of his materials and ploughs the land.

“Dr King was essentially concerned with establishing the dignity and the worth of black people within American society, but also with the plight of poor white people in the Appalachians, the poor whites who had flooded north to Chicago.

“It is extraordinary to think that when he was assassinated, he was in Memphis trying to establish better conditions of work for garbage workers in the city.

“Almost entirely made up of black men, these workers were not allowed to be members of a union and had very low wage levels.

“Dr King always said he had grown up not being conscious in his own house and family life of want or need or privation and yet he had this acute awareness of the needs of other people who were less fortunate than himself.

“It is hard to put a percentage on the number of white people who were making up the march, but I reckon it was probably 10% or 15%. And yet one had a profound feeling of community with the black men and women who were marching.

“They seemed to accept our presence, to be in a deep sense forgiving, and yet conscious of their dignity.

“The heat was tremendous – it was about 80 degrees, the hottest day of the spring. We marched in close formation, four lanes abreast, stretching for about a mile.

“There were times where the highway dipped down to a hollow and, if you looked forward or back, all you could see was a solid mass of people. For the first time, I was conscious of the power of non-violence.

“I can imagine few more powerful groups than that group of people who were marching. I felt it and it was very real to me.

“From the standpoint of history, Dr King was a giant of a man who spoke in non-violent terms to a violent society and to a largely violent world. And they couldn’t tolerate him…so they had to get rid of him.”

The marchers included the likes of Marlon Brando, Sammy Davis Junior and Eartha Kitt.

Food and cold drinks

But Mr Small was struck by the close knit camaraderie between the throng.

He added: “Following the funeral service, we walked back to Atlanta and stopped and sat on the steps of a negro Baptist church.

“Two black women in their 50s or 60s came round the corner and asked us if we were hungry. They told us they had food and cold drinks downstairs below the church and we were welcome to go down.

“My friend introduced me as being from Scotland. And these two women reacted in a fairly amazing way. They assumed I had come from Scotland to attend the funeral service and they were quite ecstatic about it.

“One of them said to us: ‘They’ve killed our leader, they’ve taken him away – and we needed him’.

“Then she said: ‘But you’ll never know how much it means to us that you have come here and joined us’.

“And in that situation, one got a glimpse of the tragedy and yet I hope, in a way, the victory as well.”

Chris Small recalled his father after the latter’s death in 2012 aged 74 and described him as “an inspiring figure within the field of education, youth and community work in Scotland”.

“He was an iconoclastic thinker whose career encompassed teaching, inspection, consultancy and mentoring.

“After studying at Edinburgh University, he worked in Aberdeen, first with vulnerable young people at St Katherine’s club and community centre, and then as a teacher at Summerhill secondary school.

“In 1967-68, he taught in Atlanta, Georgia, and was among the marchers in Martin Luther King’s funeral procession.

“After a spell teaching community and social work at Moray House, in Edinburgh, he became one of Her Majesty’s inspectors of informal further education (now called community learning), a role in which his political nous and absence of fear in confronting problems paid dividends.

“The Rev John Miller described him as ‘unnervingly creative’, with a talent for raising huge issues in unexpected ways.

“In 1980, he visited Fersands, Grampian’s poorest community. Expecting a bureaucrat, staff instead met someone totally engaged with the reality of deprivation.

“His attention to the needs of young people facing difficulties, and his understanding of the issues encountered by those who worked with them, were at the heart of the first major national report by HMI on youth work in Scotland.

“He helped set up the Scottish Youth Parliament and supported the Foyer Federation, which provides training and accommodation for disadvantaged young people.”