Few enslaved Africans were brought back to Scotland but some of those who did would become key figures in dismantling the slave trade.

Compared to the 15,000 black slaves living in England, at any given time there were 70 or 80 recorded north of the border, mostly personal servants brought back from plantations.

Black Tom

One of the justifications for slavery was that they were heathens, yet that was totally wiped out if a slave was baptised.

In England, Lord Chief Justice Hope had completely ruled out the argument that baptism conferred freedom, but in 1757 in the Court of Session in Edinburgh, Lord Bankton said the issue had not been decided in Scotland.

In 1760 Dr David Dalrymple purchased a slave in Grenada from the Home family.

Eight years later, he brought Black Tom, as he was known, to his Fife estate in Methil.

He was taught to read and it was planned for him to return to Grenada under the ownership of Dalrymple to train as a carpenter before being sold.

The day before he was due to return home, and with Dalrymple’s consent, he went to Wemyss Parish Church to be baptised, where he took the name David Spens.

The following day he packed his clothes and visited a local farmer and church elder who had supported him.

When he came back he read a statement to his master which said: “I, David Spens, formerly called Black Tom, late slave to Dr David Dalrymple, of Lindifferen, hereby intimate to you, the said Dr Dalrymple, that being formerly an heathen slave to you and of consequence then at your disposal but being now instructed in the Christian religion, I have embraced the same and been publicly baptised by the Reverend Mr Harry Spens, minister of the gospel at Wemyss.

“I am now… set at free from my old yoke, bondage and slavery and by the laws of this Christian land there is no slavery nor vestige of slavery allowed. Nevertheless you take it upon you to exercise your tyrannical power over me and would dispose of me arbitrarily at your despotic will and pleasure and for that end you threaten to send me abroad out of this country to the West Indies and there dispose of me for money.”

David was arrested and thrown into Dysart jail, from where he summoned several lawyers who worked for him for free.

He began issuing writs against his master and the sheriff’s officers for wrongful arrest.

David was released on bail but his master died in 1770 before the Court of Session decided the case and he became a free man anyway.

While little is known about what happened to him afterwards it seems that miners, salters and churches in the area collected money for his support.

Joseph Knight

One of the most important legal decisions in the struggle to end slavery began in Perthshire and again ended up at the Court of Session in Edinburgh.

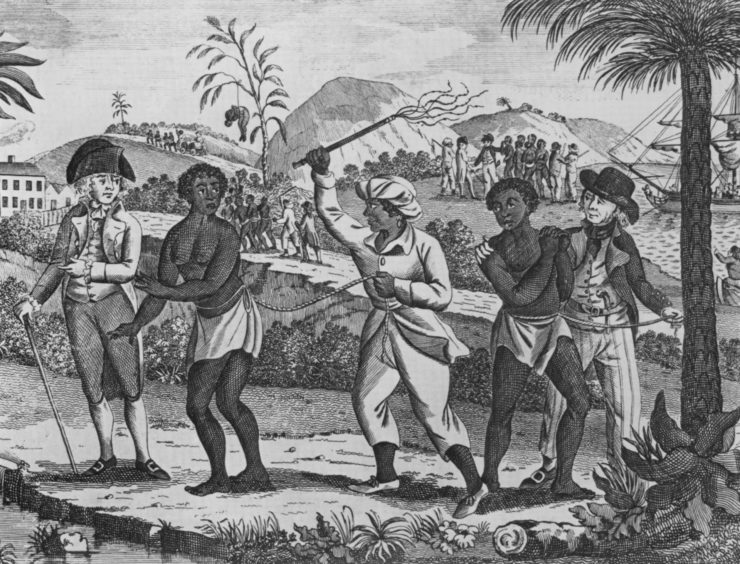

Joseph Knight was captured during the height of the slave trade before being sold to wealthy Scottish plantation owner Sir John Wedderburn in Jamaica, where he would be forced to work as a domestic servant.

Wedderburn was a Scot who had amassed a fortune in Jamaica before coming home to Ballindean in the Carse of Gowrie.

He brought Knight back from Jamaica in 1769 and wanted to retain his unpaid services.

Knight married one of Wedderburn’s maids, a Dundee girl called Annie Thomson, who ended up getting the sack and returning to her home town.

Knight wanted to go with his wife and seek paid employment elsewhere, but his master forbade it and to back him up he brought in magistrates, who were all his pals.

Knight mounted a legal challenge against Wedderburn in the Justices of the Peace court in Perth in a bid to seek freedom in 1774.

He claimed that the act of slavery was not recognised in Scotland like it was in Jamaica.

The court ruled in favour of Wedderburn, which prompted Knight to launch an appeal to the Sheriff of Perth, John Swinton.

He found that: “The state of slavery is not recognised by the laws of this kingdom, and is inconsistent with the principles thereof: that the regulations in Jamaica, concerning slaves, do not extend to this kingdom; and repelled the defender’s claim to a perpetual service.”

The ramifications of this dispute reached far and the case became an opportunity for Scotland’s supreme civil court to examine the whole question of slavery.

It ended up going through the Court of Session for years until January 1778 when it was ruled that, as there was no such thing as slavery in Scotland, Knight couldn’t be held.

Lord Kames said “we sit here to enforce right not to enforce wrong” and the court emphatically rejected Wedderburn’s appeal, ruling that “the dominion assumed over this Negro, under the law of Jamaica, being unjust, could not be supported in this country to any extent”.

William Dickson

In 1788, of the 170 appeals to parliament against slavery, only 16 came from Scotland.

The total number went up to 560 within four years and by then 185 – roughly a third – were from Scots.

The increase was largely the work of a Moffat man, William Dickson, who, as secretary to the governor of Barbados, had witnessed the inhumanity first-hand.

Returning to Britain he joined the Abolition of Slave Trade Committee in London and in 1792 they sent him on a nine-week tour of Scotland to drum up support and signatures.

Dickson arrived in Aberdeen and stayed there for several days before heading off on a lengthy tour that took him up to Meldrum, Turriff, Banff, Portsoy and Cullen, across to Inverness, and then back down to Aberdeen, via Fochabers, Keith and Inverurie.

Some 10,000 people put their names on a petition in Edinburgh.

It was the third largest number after London and Manchester.

An Address to the People of Great Britain on the propriety of abstaining from West India Sugar and Rum, which was printed in Dundee in 1792, claimed a circulation of 70,000 in four months and that “upwards of 25,000 people had given up sugar and rum.”

Later that year, Prime Minister Robert Peel’s Chief Minister, Henry Dundas, announced the slave trade would be abolished ‘gradually’.

It wasn’t until March 25 1807 that the Slave Trade Act was passed.

But only the buying and selling of slaves was banned.

James Stephen

The owning of slaves continued until 1834, when the Slavery Abolition Act (1833) took effect and it was finally prohibited throughout the British Empire.

The architect of the Abolition Bill was James Stephen, who was born of Scots parents and was educated at Marischal College in Aberdeen.

Stephen resigned his parliamentary seat in April 1815 to concentrate on writing and published in two volumes, The Slavery of the British West India Colonies Delineated (1824 and 1830).

The book provides a comprehensive and detailed picture of the British West Indian slave system in the early 19th century.

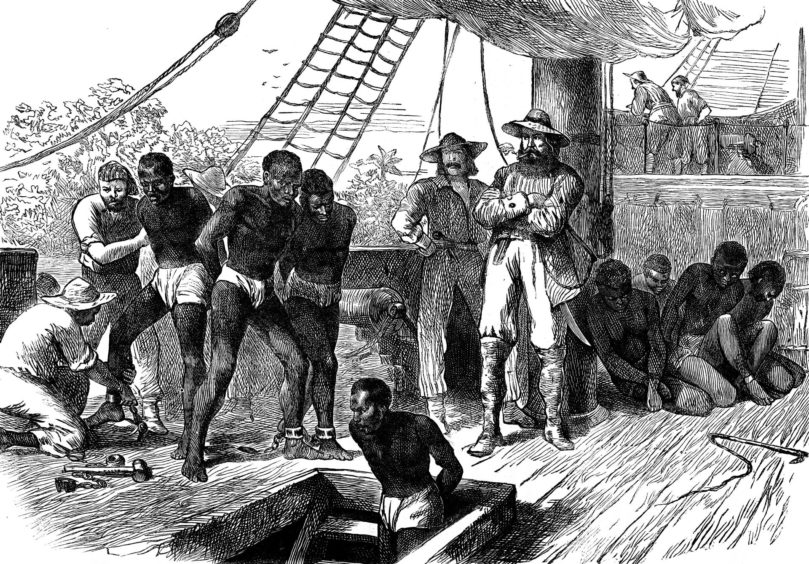

Young people were kidnapped off the city streets and sold as slaves

Indian Peter is a story embedded in Aberdeen folklore, of an 18th century man who dressed as a Cherokee and sold pamphlets on the streets of the Granite City about his extraordinary life.

Behind that colourful tale lies a glimpse of a grim chapter in Aberdeen’s history when children and young people were kidnapped off the city streets by roaming press-gangs, shipped to America and sold as slaves to work in cotton plantations.

Indian Peter

Peter Williamson was one of them.

Born in 1730 near Aboyne he was sent to stay with his aunt in Aberdeen when, just nine years old, he and a playmate were lured onto a ship in the harbour, then held prisoner before being packed off to the plantations.

The pair were victims of a flourishing trade in selling children to be transported into slavery in the colonies, with city magistrates, merchants and officials colluding in the illegal commerce.

Syndicates were formed, with press-gangs even raiding remote villages of the north-east, snatching victims.

The books of these syndicates reveal some parents sold their own children and relatives into slavery.

It is thought between 1740 and 1746 alone, 600 youngsters from the north-east were shipped to North America.

Most were never heard of again – unlike Peter.

He survived the 11-week crossing only for his ship to be wrecked off New Jersey.

Sold for £16

He was then sold as a slave in Philadelphia for £16 and indentured to a rich planter, Hugh Wilson.

Wilson was a Scot who had, himself, been sold into slavery but escaped.

He treated Peter like a son and paid for his education.

When Wilson died, he left the 17-year-old £120, a horse, saddle and wardrobe of clothes.

Peter then fell in love with and married a planter’s daughter, settling by the Delaware River with a dowry of 200 acres.

But an attack by a Cherokee war band saw him captured and his home razed to the ground.

During this time he was treated as a human packhorse by the Cherokees, flogged and witnessed other homesteads torched and settlers murdered.

It was a period of his life that was the basis for the Richard Harris film, A Man Called Horse.

Peter managed to escape and find his way back to his father-in-law’s plantation, only to discover his wife had died two months before.

Pledging revenge, he joined the British forces to fight the French and their native allies.

Captured by the French he was part of a prisoner exchange and shipped to Plymouth.

Whooping and screeching

Penniless, he was determined to return to Aberdeen, walking most of the way. He supported himself by selling a pamphlet about his life story on street corners while dressed as a Cherokee, whooping and screeching until he attracted a crowd.

He continued to do so once he arrived in the Granite City, completing his transformation from Peter Williamson to Indian Peter.

The authorities of the day, outraged by his accusations, accused him of libel.

The offending pages of his books were ripped out and burnt at the market cross by the city hangman and Peter was jailed until he signed a declaration saying his story of the kidnapping was false.

Fined 10 shillings and banished from Aberdeen, he went to Edinburgh. He set up a coffee house next to the Scottish Parliament, which became a haunt for lawyers.

When his customers learned of his story, they encouraged Peter to sue the magistrates of Aberdeen for imprisoning him. The Court of Session found for him and he was awarded £100 from the Provost of Aberdeen, four Bailies and the Dean of Guild.

Peter went on to run a tavern, then start a printing house, compiling Edinburgh’s first street directory.

He also started the city’s first penny post service.

He died in 1799, having fathered nine children, and is buried in Edinburgh’s Calton Cemetery.

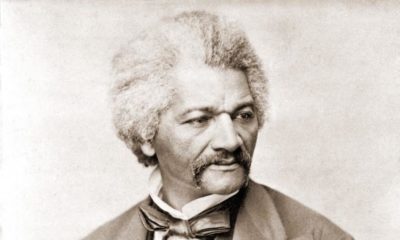

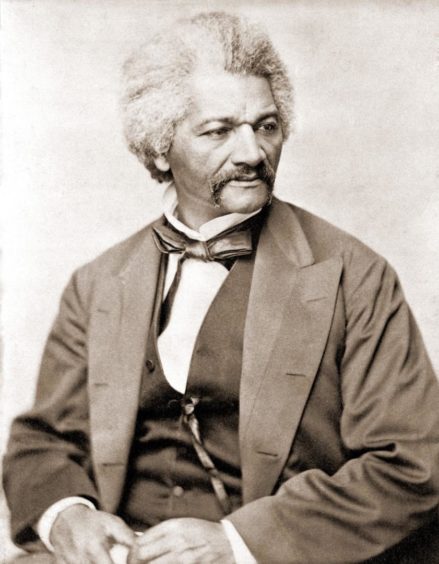

Frederick Douglass and the speeches which tried to rally British support

Formerly enslaved African-Americans made radical and politicised journeys to the British Isles during the 19th century to educate audiences about slavery, racism, and lynching.

They spoke in large cities and small fishing villages and published thousands of copies of their slave narratives.

Frederick Douglass became the most famous African-American in the transatlantic world and worked as an abolitionist, civil rights activist, feminist, writer, orator, and advocate of social justice throughout his life.

He travelled to Britain and Ireland in 1845 for 19 months, lecturing against American slavery around 300 times.

His lectures were brilliant works of oratory and the controversies Douglass created illustrate his electrifying capacity as a performer.

Douglass returned to the States in 1847 a free man: British abolitionists had purchased his legal freedom.

Dr Hannah-Rose Murray, a research fellow at Edinburgh University, has created a website (www.frederickdouglassinbritain.com) dedicated to the experiences of formerly enslaved African-Americans like Douglass and has mapped their speaking locations across Britain, showing how they travelled far and wide to raise awareness of American slavery.

Her “abolitionist maps” chart the places – many are in Fife, Dundee, Perthshire, Angus, Moray, Aberdeenshire and Inverness – where they tried to rally British support for US abolition.

Dr Murray said: “The maps of their speaking locations are designed to be visual monuments of their courageous and inspiring activism.”

Other black abolitionists on her maps include Josiah Henson, William Wells Brown, William and Ellen Craft, Moses Roper and Henry ‘Box’ Brown.