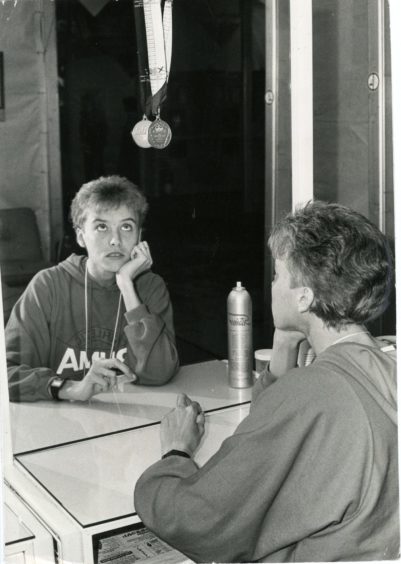

Liz McColgan has never forgotten the tidal wave of emotion which enveloped her when she stood on the gold medal podium in Edinburgh at the 1986 Commonwealth Games.

Two of her friends had struck a wager with the Dundee athlete that she would cry during the ceremony. Lynch, who later became better known as McColgan, insisted that she wouldn’t.

But when the anthem started playing and she listened to the rapturous ovation from the packed crowd at Meadowbank Stadium, even this redoubtable competitor, who surged to victory in the 10,000m at the outset of a brilliant career, was overcome by emotion and the tears flowed.

As she recalled: “I didn’t think I would do that, but the crowd were something else and Scotland the Brave sounded so wonderful.

“It was so overwhelming and totally unbelievable. I could never, ever relive that moment.”

Sadly, she was not the only person who was weeping by the end of an event which provided a stark contrast with the previous Games which had been staged in Edinburgh in 1970.

The latter was a joyous celebration of sport with a litany of feelgood stories, showcasing the beauty of Scotland and graced by beautiful weather.

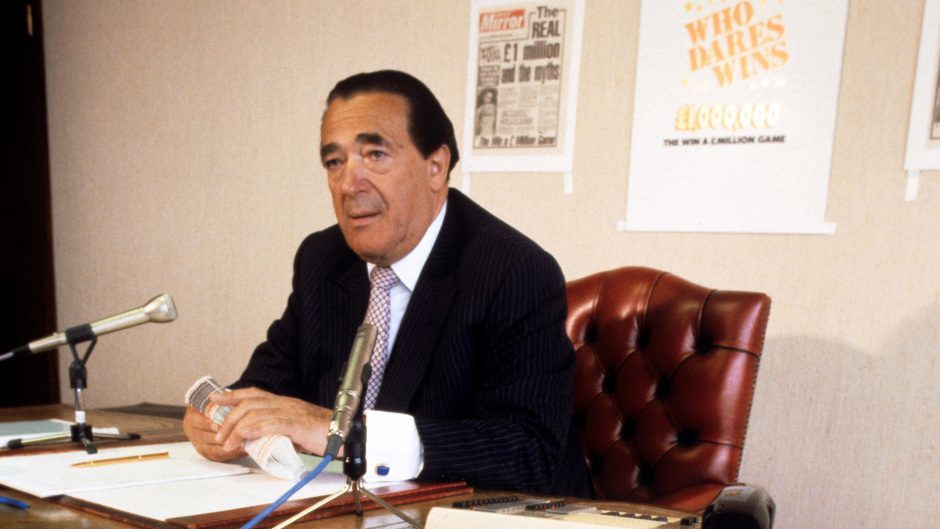

But, 16 years later, amid accusations of amateurish organisation, bungled and/or financial mismanagement, and with the number of participants massively reduced by a boycott from the African nations, these Games were dominated by the spectre of the late newspaper magnate, Robert Maxwell, who took centre stage in the farce.

Looking back, there was nothing wrong with the spectacular cast list who lit up the track and field programme. Steve Ovett left the 800m and 1500m races to Steve Cram, and participated in the 5,000m, which he won convincingly.

Daley Thompson triumphed in the decathlon, while Linford Christie was beaten in the 100m by Ben Johnson, who was subsequently disgraced at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul after testing positive for drugs.

Steve Redgrave was already a major performer in the water and secured three rowing golds and Lennox Lewis was victorious in the super-heavyweight division – against an opponent who didn’t have to throw a single punch to book himself a silver medal.

Aneurin Evans, a young Welshman who wasn’t even a household name in his own living room, was the fellow who clambered into the ring against Lewis, at that stage representing Canada. It was a dire mismatch which was neatly summed up when BBC commentator, Harry Carpenter, remarked: “If I were him, I’d be running for my life.”

The mass boycott of the Games damaged boxing more than any other sport.

Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda and Zambia all had powerful contenders who might have punched their way to glory in the different weight categories, but were stymied by the politicians.

And, as the opening ceremony loomed with countries withdrawing right up to the eleventh hour – in protest at the British Government’s links with apartheid South Africa – the fears over the economic viability of the Games threatened to take precedence over any achievements by the athletes themselves.

All of which explains why Maxwell – or “Cap’n Bob” as he was known in Private Eye magazine – became such a pivotal figure in the spiralling circus.

He boasted about having made a fortune from publishing, but couldn’t shrug off the accusation that he was “not a person to be relied upon to exercise proper stewardship of a publicly quoted company”, according to the Department of Trade. And even now, nearly 30 years after his death in November 1991, controversy plagues him and his family.

Maxwell plundered the pension schemes of thousands of his employees and consigned their futures to a black hole.

With hindsight, it wasn’t a surprise that such a quixotic character played a prominent role in what were the most bizarre, benighted Games ever staged.

A few weeks before the opening ceremony there had been talk of crisis, even of cancellation. More than half of all Commonwealth nations eventually stayed away, as did the blue-chip corporate sponsors who might have kept Edinburgh in good health.

But Maxwell himself was typically bombastic, oozing bravado and boldness.

He said he was “the saviour” of the Games and was introduced to the Queen in Edinburgh by his personal photographer and aide Mike Maloney, who had been on many royal assignments.

He handed the monarch a set of coins in a magnificent display box, and boomed: “Permit me to present you with a token of this great event I have orchestrated.”

Thankfully, in the midst of all the acrimony and rancour, another Liz – Miss Lynch as she was at the time – transcended the grandiose theatrics with a lung-bursting display at Meadowbank.

A burden of expectations had been heaped on her shoulders when several fancied Scots struggled to pursue an elusive gold medal in their homeland. One by one, they ran, and one by one, they faltered….but not the Dundonian.

She told me: “It was probably one of my greatest-ever moments to be in front of a full stadium and everyone shouting your name.

“There was a lot of pressure on me as it was the last opportunity of a gold medal for Scotland in track and field.

“I remember being in the residences and Tom McKean took part in the 800m and didn’t win, then Yvonne Murray didn’t win her event and both had been favourites to gain the gold.

“As I left to go to the track, the team manager turned and said to me: ‘Liz, you are our last hope’, which was absolutely the last thing that I needed to hear.

“But it was amazing being Scottish and running in these Edinburgh Games. The support was electrifying and they were all willing you on.

“I was very confident of winning and felt really strong throughout my 25 laps, but every lap that passed, you could sense the spectators realising this might be the gold and it got louder and louder as the race went on.

“I knew from 1000m out I had won, so I had two and a half laps of soaking up the atmosphere. It never felt the same in any other championship in which I competed – that feeling of everyone in the stadium wanting you to win.

“My preparation had started four years earlier and my coach had told me that the 10k would be introduced for the first time.

“So I started doing lots of work toward getting stronger over the distance, because until then, we could only race up to 3,000m.

”It was a huge thing for me to win and it really set up my career path. For the Games, I purposely worked on doing more miles and longer preps and that was specifically aimed at being at my best in the 10,ooom.”

Even after the dust had settled on the 1986 festival, people were continuing to argue and dissect Maxwell’s machinations a decade later and the general conclusion was that he had promised a lot more than he had actually delivered.

By then, he was long dead and his demise happened in mysterious circumstances. In November 1991, Maxwell fell overboard from his private yacht in the Mediterranean.

It was a tragic end to a scandal-plagued life and the stories abounded of how he schmoozed his way around Edinburgh during the Games, handing out medals to bemused winners from far-flung nations after pledging he would do no such thing.

Then there was the time he invited a number of VIPs and their partners to dinner at his private suite and promised them a meal they would never forget.

His guests might have been expecting champagne and caviare or a few tasty treats from the nearby oyster bar. But he served up Kentucky Fried Chicken straight from the bucket and tucked in with a Bunteresque relish.

On another occasion, his flash limousine broke down while he was en route to a medal presentation. Undaunyed by this setback, he simply commandeered one of the athletes’ private vehicles, demanded a lift to the Sheraton Hotel, and wrote a “note of absolution” to the driver.

Peter Heatly, who was later knighted for his services to sport, had originally suggested that Edinburgh should bid for the event for a second time.

As a former gold-medal-winning diver at the Olympic Games, who eventually secured the role as the leading figure in the Commonwealth Games Federation, the Scot possessed the expertise and experience to make things happen in his domain.

But that didn’t extend to persuading political leaders not to withdraw from the Games schedule as political pressure mounted and the snowball gathered momentum.

He later recalled: “Talk of a boycott had always been around, but when it hit, the full extent and range of it surprised almost everybody.

“It broke 10 days before the Games and, every morning, you would wake up and another country had decided not to come. It was terrible.

“You died a little bit every morning over the course of those 10 days”.

The final loss was devastating: 32 teams and nearly 1,500 athletes stayed away and, in the process, inevitably diluted the standard of performance in some events and – as in boxing – reduced the competition to absurdity.

No wonder, therefore, that Edinburgh’s pride at becoming the first city to stage the Games twice quickly evaporated when the grand panjandrum Maxwell arrived on the scene and cast his shadow all over the proceedings.

One of his first pronouncements was that the early preparations for the international event had been “appallingly amateurish” and, to be fair, there were indications his assessment was accurate.

But there again, nobody else had tabled a bid to stage them, apart from the Scottish capital. And if the initial organising bodies made mistakes, at least they didn’t indulge in the ostentatious opulence which surrounded Maxwell.

As one of his colleagues later recalled: “He ordered a banquet for 14 people from Edinburgh’s top Chinese restaurant.

“There was plenty of Dom Perignon. When he said ‘Tuck in’, I asked if we wouldn’t be better waiting for the other guests to arrive. But it turned out there wasn’t anbody else – there was enough food for another 12 people and he just got stuck in, sometimes with his fingers.

“There was curry sauce dripping down his shirt when he went off to bed.”

Maxwell’s preferred setting was not the stadium – it was in front of the cameras with an explosion of flashlights and reporters lapping up his big promises and he was the sort of self-absorbed individual who took a bow when he opened his fridge door.

Yet even though the Games’ administrative company faced a labyrinthine task in balancing the books and many bills remained unpaid in perpetuity, it’s still possible that the whole event would have collapsed without his intervention.

And that, of course, would have denied us all the chance to cheer on our Liz!

As she said: “Edinburgh was the starting point and it made me believe that I could win major championships titles, so it was the perfect stepping stones to my future success at World and Olympic level.

“I actually semi-retired before the 1990 Commonwealth Games (in New Zealand) because I was bit disillusioned with athletics when I got the silver in the 1988 Olympics. So I had some time out from the sport and I only decided 12 weeks before the 1990 Games began to start training and have a go at retaining my title.

“When I look back now, I realise that I was lucky to win when I raced in Auckland because I was not in my best shape.”

She has always been her own toughest critic. But, if everybody else had shown the same professionalism and pride in performance, Edinburgh might have gained the same positive reception as she did from the Meadowbank throng.