He was one of the bravest men of his generation: a gentle giant who broke records and raised spirits on the ground and served his country in the air.

And, even now, 68 years after his death on Loch Ness while he attempted to establish another new milestone for his serried CV, John Rhodes Cobb’s name evokes poignant emotions among those who have studied the life and times of this pioneering fellow.

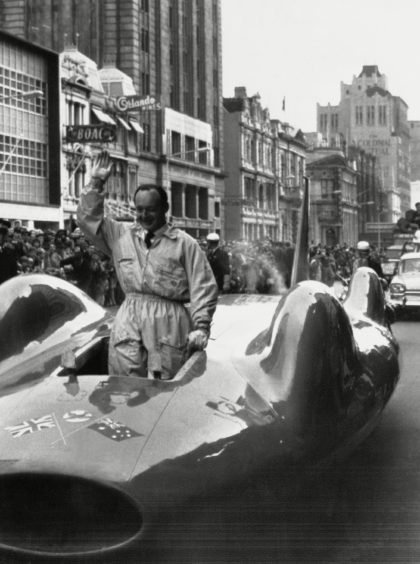

When his hearse was conveyed through the streets of Inverness, following his death at high speed on September 29 1952, thousands of people lined the streets, not simply to pay tribute to a remarkable character, but to honour an Englishman who respected the Highland way of life and refused to test run his vehicles on Sundays because he understood that the Sabbath was a day of rest and prayer in the north of Scotland.

He was already a three-time holder of the World Land Speed Record, in 1938, 1939 and 1947, which had been set at Bonneville Speedway in Utah and was awarded the prestigious Segrave Trophy as his achievements and accolades were toasted throughout the globe.

The quiet, self-effacing hero, who preferred to let his accomplishments speak for themselves, paid the ultimate price whilst piloting a jet-powered speedboat in his bid to break the World Water Speed Record on Loch Ness.

But, if there were contradictory reports and an element of controversy about the precise cause of his demise, which was captured by a film crew, that didn’t diminish the scale of the tragedy or the impact which it had on the crowds who turned up to watch his attempt.

Birth of a legend

Cobb was born in Esher in Surrey, on December 2 1899, near the Brooklands motor racing track which he frequented as a boy.

He received his formal education at Eton College and Trinity Hall in Cambridge, but while he became a successful businessman in his personal life, the youngster was mesmerised by machinery and motors and travelling as fast as he possibly could.

In 1924, he acquired a Royal Aero Club aviator’s certificate, qualifying as a pilot on a Sopwith Grasshopper and he won his first track race in a 1911 10-litre Fiat in 1925, and raced in the Higham Special at Brooklands race track the following year.

The honours and commendations kept stacking up.

In 1933, he privately commissioned the design and construction of the 24-litre Napier Railton, with which he shattered a number of track speed milestones, including setting a lap record at the Brooklands race track which was never surpassed, driving at an average speed of 143.44mph.

At the helm of the piston-engine, wheel-driven Railton Special, this redoubtable fellow broke the World Land Speed Record at Bonneville salt flats on September 15 1938 by pushing the throttle to 350mph, then smashed it for a second time at the same site on August 23 1939, attaining 369mph as he and his colleagues ramped up their efforts.

During the Second World War, he was a pilot in the Royal Air Force, and between 1943 and 1945, served with the Air Transport Auxiliary, ultimately being demobilised with the rank of Group Captain after making an appearance in the wartime propaganda film Target for Tonight.

Bolstered by an unquenchable spirit, he managed to increase his land speed rate to above 394mph two years after the end of the war, but at the stage where others might have thought about winding down a little, Cobb turned his mind to becoming on water what he now was on land, and embarked on his pursuit of the simultaneous World Water Speed Record.

He commissioned from Vospers the jet-engine powered speedboat Crusader, and selected Loch Ness in Scotland for the speed trial. He enjoyed such an exalted reputation that few people imagined he would not thrive in this new challenge, even in his early 50s.

But, as Adrian Shine of the Loch Ness Project told me, the whole venture was rushed and there wasn’t the same amount of preparation as Cobb had shown in his previous endeavours.

He said: “He was due to take over the chairmanship of the Falklands Company and I believe that distracted him from focusing as much on this particular record attempt.

“There were suggestions that further tests should be carried out on the Crusader before the bid was launched, but John Cobb signed a disclaimer, the plans went ahead as originally scheduled and, of course, we know what happened.

“He and his team had chosen Loch Ness because it was long and straight, which was considered ideal conditions, but I think it was also a trap, because the loch was directly in the line of south winds which created difficulties for those on the water.

“That was what caused initial problems on the day.

“A breeze got up and John Cobb went back to the Drumnadrochit Hotel, but he then received the news that the wind had subsided.

“So he returned to the Loch and they all decided to press ahead. Crusader was got ready, two flares were fired, the weather calmed, and the attempt went ahead.

“John was experienced, he had been involved in so many of these ventures before, but there was a sense that this was carried out before everything had been properly checked.”

During the ill-fated run, the boat hit an unexplained wake in the water and quickly disintegrated about Cobb, who had reached a speed of around 200mph.

His body, which had been thrown 50 yards beyond the wreckage, was subsequently recovered from the loch, but the incident understandably sparked shock and consternation among the large numbers of the local community who had congregated at the famous site.

A memorial was erected on the Loch Ness shore to his memory by the townsfolk of Glenurquhart.

It is still methodically tended more than 70 years after Cobb lost his life.

Highland hero

And Mr Shine has no doubts about why he is held in such affection in the Highland capital.

He said: “He was enormously respected by all those who met him, he was quiet, courteous, in no way flamboyant or egotistical and he made a favourable impression on so many people.

“He was called The Gentle Giant and that summed him up. Sometimes, with people who are obsessed with breaking records, it is all about them and nothing else matters.

“But John Cobb wasn’t like that. I remember talking to an old farmer who had run out of petrol on his tractor on some remote country road.

“He told me that Cobb drove past in his big car, stopped the vehicle, and arranged for the farmer to be given a can of petrol, which made all the difference. It’s maybe a small thing, but the local community had other examples of how he fitted in.

“After his death, there was a real air of sadness and the affection for him was obvious when so many people turned out on a wet day in Inverness and said a heartfelt goodbye to him.

“I think he fully deserved that send-off when you look at his remarkable exploits.”

Long quest to find the Crusader paid dividends in 2019

The search for the boat which was used in a tragic speed record attempt on Loch Ness was finally brought to an end after a 17-year quest by experts in 2019.

John Cobb’s body was discovered on the surface at the time, but only small fragments of the vessel were recovered, with the main body sinking to the depths of Loch Ness.

However, the discovery of the impressively intact hull was made by the production crew of a new instalment to the National Geographic Drain the Oceans TV series.

The team, in collaboration with Kongsberg Maritime and the Loch Ness Project, used the latest robotic technology to scan the depths of the famed stretch of water, to produce the highest resolution and accurate sonar readings ever undertaken on Loch Ness.

During the scan, the wreckage of the Crusader was established with a remote-operated vehicle sent to explore further the anomaly.

And the footage revealed the first underwater images of the craft.

Adrian Shine of the Loch Ness Project said: “Back in 2002, we found bits of aluminium but we did not find an engine, so really we had unfinished business.

“The discovery is certainly of national significance. This really did bring an end a 17-year-old quest for us.

“John Cobb was a national hero as the holder of the land speed record and he went down very well in Drumnadrochit.

“It is one of those bittersweet moments. We have succeeded in what we set out to do but it is then you realise you are looking at a tragedy, and that was not lost on us.

“I was highly surprised to see how intact the vessel was.”

Historic Environment Scotland has been notified of the discovery, but there are no plans to raise the wreck, which was designated as a nationally important scheduled monument in 2005.

Bill Smith of the Bluebird Project, who have extensively restored one of the crafts used by the former world record holder and fellow daredevil Donald Campbell, said that the project team was not actively pursuing the opportunity to restore the Crusader.

He added: “Certainly, if somebody came to us and asked us to salvage and restore the Crusader then yes, we would be interested in getting it done.

“It would be a privilege. But it is not anything to do with us. If we were to get involved it would have to be in a similar method to the Bluebird Project whereby we were invited and are merely the instruments at the disposal of the Campbell family.”

Instead, the Crusader will be allowed to rest where it was the scene of a Highland tragedy.