The Elephant Man could never forget the kindness shown to him by a young widow from the Isle of Islay which changed his life.

Leila Maturin was said to have been the first woman to smile at Joseph Merrick and shake his hand and thanks to her he started to see himself as a human being rather than a monster.

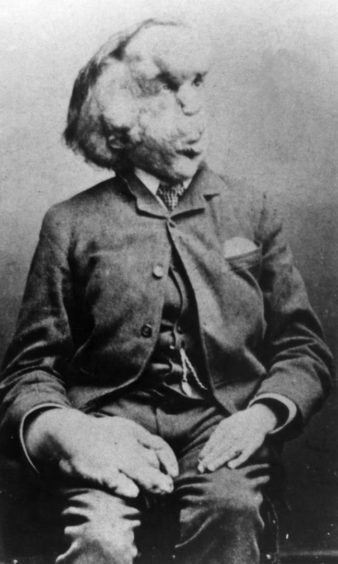

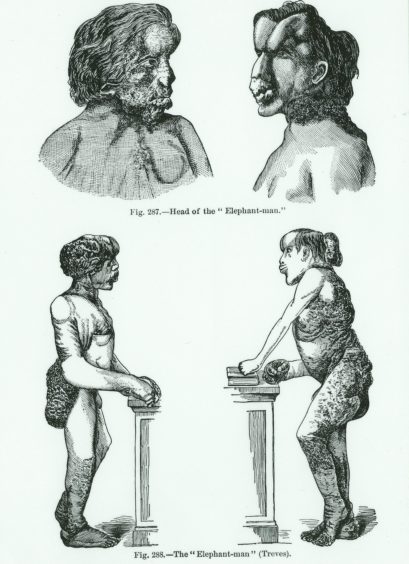

The cause of Merrick’s disability is still open to debate but the most popular diagnosis is Proteus syndrome, a rare condition characterised by overgrowth of the bones and skin.

Human curiosities

Merrick frightened and thrilled those who paid to gawp at him in Victorian times when it was common for showmen to make money showing human curiosities for public entertainment.

But he was genuinely worthy of academic study.

A surgeon, Frederick Treves, sought out Merrick and asked him to come to the London Hospital, against all rules and regulations.

For the first few weeks in hospital he just lay in his bed with his head in his hands, speaking to no one.

Dr Treves knew hardly anyone had ever spoken kindly to him.

Leila was a “a young and pretty widow” and Dr Treves asked if she would be willing to meet this man, be able to show no disgust, shake his hand and smile at him.

Without hesitation, she agreed.

She “entered with easy grace, smiling as she approached” and sat down by the bed, and took his hand.

“Hello,” she said.

“How are you?”

Merrick gripped her hand, then began sobbing, crying for a long while, making the visit cut short.

They were probably the first gentle words he’d ever heard.

From that moment his progress was rapid.

He later told Treves that Leila had been the first woman ever to smile at him, the first to shake his hand.

He never forgot Leila and wrote regularly to her to her home in Islay.

The mystery remains as to how Leila was known to Dr Treves who practiced in London.

It is possible that her father may have been fascinated by Merrick as he was the most likely of the family to have had connections to such a person as Dr Treves.

Though Dr Treves did not name her in his book, only describing her as an attractive young widow, a subsequent account in The History of the Elephant Man by Michael Howell and Peter Ford, identified her.

Envelope and letter

That book also reproduces an envelope and letter from Merrick to “Miss L Maturin, Sunderland House, Islay, West Coast of Scotland” which was written on October 7 1889.

“Dear Miss Maturin,

“Many thanks indeed for the grouse and the book you so kindly sent me, the grouse were splendid.

“I saw Mr Treves on Sunday, he said I was to give his best respects to you.

“With much gratitude I am Yours Truly.

“Joseph Merrick, London Hospital, Whitechapel.”

Leila was born in Haddington, East Lothian, on December 29 1854 where her father, Robert Scot Skirving and his wife Leila, who was from Irish stock, had a large farm at Camptown by Athelstaneford.

Leila junior was the only daughter of seven siblings including David, Owen, Robert, William, Edward and Archibald Adam.

Leila attended school in Edinburgh until she was 17 and then went to Paris before her mother died in 1874 and she put her own life on hold to bring up her young brothers and look after her father.

Leila eventually married Lesley Maturin in 1883 although the marriage was short lived and he died within a few months.

Michael Osborne runs the Maturin family website and said it was “heartening to hear that Leila has not been forgotten”.

He said: “My connection to Leila is a step removed in that my wife Anne was the great-great-granddaughter of Reverend Edmund Maturin, who was the youngest brother of John Maturin, who was Leslie Maturin’s father.

“I thoroughly enjoyed researching her life as she gives the impression of being a gentle, kindly woman who deserves some sort of memorial.

“In fact recording such stories has been the main reason for the website as there are a few others who have a direct interest.

“Only two branches of the Maturin families now live in the UK with one more in New Zealand.

“All the other lines have died out.

“Of Leslie’s six siblings only his brother Frederick had children and I have not been able to find any descendants from them.

“Leila had six brothers but I have not traced them as they were a step removed from the main thrust of my aims.”

Isle of Islay

Michael said Leila’s father was passionate about wildlife and had campaigned hard for the bill to preserve Bass Rock in the Firth of Forth as a bird sanctuary.

He said: “Following his wife’s death he immersed himself in nature and stayed for about six months each year at Sunderland House on the Isle of Islay in the Inner Hebrides.

“It is likely that the widowed Leila dutifully and regularly accompanied him as it was to that address that Joseph Merrick, the Elephant Man, wrote his only preserved letter.”

He died in Edinburgh in 1900 after suffering from heart disease for five years.

Leila never remarried.

She died on February 27 1917 in Edinburgh aged 62.

Her brother Archibald informed the authorities after the coroner had certified death from “Influenza and sudden heart syncope”.

She was taken back to be buried with Leslie in Mount Jerome, Dublin – close to her Owen relations.

Life and times of Joseph Merrick

Merrick’s disability did not begin to show until he was five.

His mother died from unknown causes when he was just 11, and his father — also Joseph — soon remarried.

Merrick checked himself into the Leicester workhouse aged 17, where the destitute were given food, shelter and work.

After four years there Merrick contacted music hall manager Sam Torr with a business proposition: that the showman should exhibit Merrick.

He was soon touring around clubs in the East Midlands before he moved to London, where he met his next agent, Tom Norman, who set up the Elephant Man show on Whitechapel Road which was opposite the London Hospital.

For a fee, Norman would tell crowds a myth of how, at his birth, Merrick’s mother was stamped on by an elephant, resulting in a half-man, half-elephant creature.

He would pull back a curtain to reveal Merrick, leaving audiences gawping in amazement.

Dr Treves visited the show and invited Merrick to the hospital to be examined and photographed.

Police shut down Merrick and Norman’s show as a public nuisance before he spent three months with a travelling circus in Northamptonshire.

His real ambition was to entertain audiences in Europe, so he advertised in the papers for a new manager who could take him to the continent.

Merrick seems to have been robbed and abandoned by his new management, leaving him in Brussels without a penny to his name.

With great difficulty he made his way back to London and made contact with Treves who invited him to stay at the hospital.

Merrick died at the age of 27 and he was found lying across his bed as if he had slipped and was trying to get up.

On his death Merrick’s skeleton was preserved at the London Hospital but his soft tissue was buried in the City of London Cemetery.

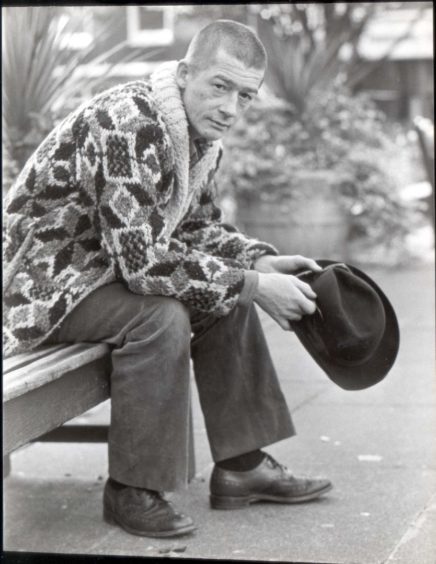

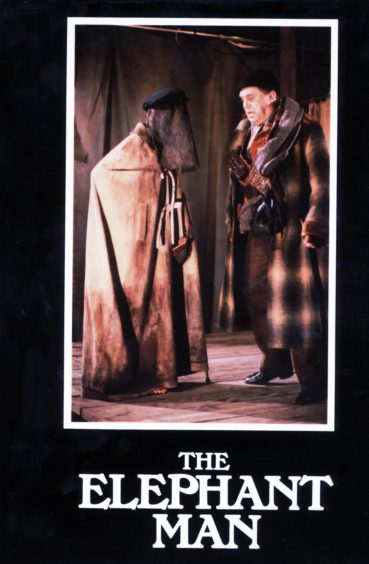

Frederick Treves wrote the book The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences in 1923 and Merrick’s life story was made into a film in 1980 and shot in black-and-white.

The Elephant Man was a critical and commercial success with eight Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Actor.