Welcome, my friends, to an alternative history of Scottish football; a world where anything was possible and where serious proposals were devised for schemes which would have shaken up the game to a remarkable extent.

Alright, perhaps it needs Rod Serling, creator of The Twilight Zone, to deliver these sort of introductions in his inimitable style to send apprehensive shivers up the spine.

But, in his absence, let’s proceed with the revelation that Hibs were so fed up with their nomadic existence in the early 1900s that they actively considered relocating to Aberdeen – and made approaches to officials in the Granite City to implement the proposal.

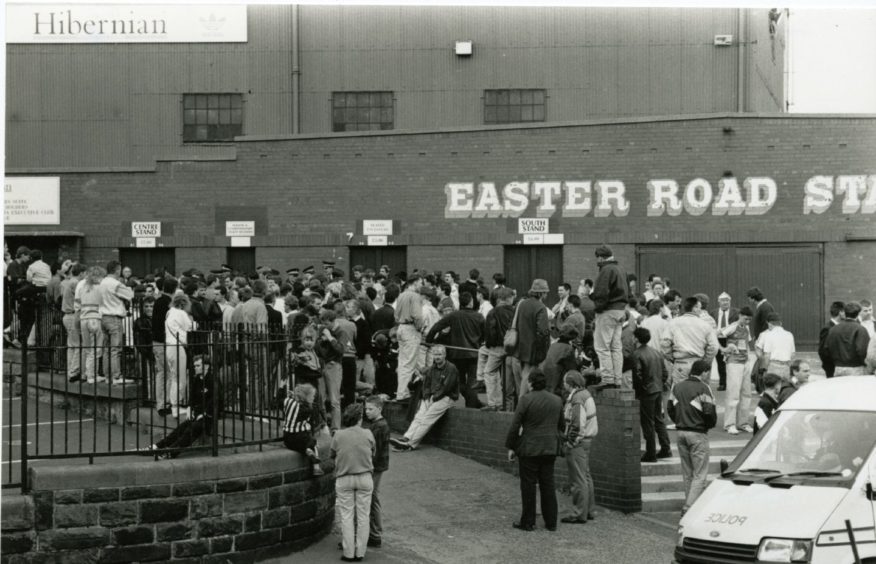

Yes, we are talking about Hibs, an organisation which has become synonymous with Easter Road, The Proclaimers’ Craig and Charlie Reid, the anthem/chart hit/film Sunshine on Leith, the fabled Famous Five from the 1950s, the late Sir Sean Connery and tennis Grand Slam champion Andy Murray.

And yet, even as they considered creating a new stadium and prepared for the future 120 years ago, they were in regular contact with authorities in the north-east, at a stage before Aberdeen FC had even been established.

Edinburgh club

Maybe, it shouldn’t be considered so surprising. After all, while many people erroneously describe Hibs as an “Edinburgh club”, they have always been proud of their connections with the port of Leith; a place with such a distinctive identity that it was once entirely separate from the capital, boasting its own town hall and coat of arms.

Fraser Clyne, who wrote a book about these Victorian days called, ironically, The Aberdeen Men Can’t Play Football, has investigated his subject thoroughly – and his work has been bolstered by research from the Aberdeen FC Heritage Trust.

Mr Clyne said: “In autumn 1902, rumours were spreading within the Aberdeen footballing community that Hibernian were considering relocating the club to the Granite City.

“Speculation was rife that Hibs representatives had travelled north to try to agree terms for leasing Pittodrie – which had opened in 1899. At the time, Hibs were one of the pre-eminent teams in the Scottish League and, if they had moved to the north-east, it would have brought first division football to the city.

“It is hard to substantiate whether there was any truth in the rumours. It may well have been a story that individuals who supported the idea of merging the city’s three senior clubs – Aberdeen, Orion and Victoria United – set them in motion to scare those who were against the proposed amalgamation and force them into action.

“Or was it really the intention of those behind the Edinburgh club to capitalise on the opportunity provided by the potential of locating the already established Hibees – who were founded in 1875 – in an area where there was no senior competitor?”

Northfield

There was no doubt that the idea was considered and, from a commercial perspective, it made a lot of sense. Hibs were determined to find a genuinely fit-for-purpose stadium and they considered all manner of alternatives, including a “ghost” ground at Northfield – the area in Edinburgh, not that of the same name in Aberdeen.

Journalist Patrick McPartlin has examined the history meticulously in recent months and told the Press and Journal of how Scottish football could have been so dramatically different.

He said: “It’s certainly strange to think of Hibs playing anywhere else but at Easter Road, but it gives us an insight into how difficult it could be in the late 19th century for clubs seeking long-term homes.

“Space in Edinburgh for playing first-class football seems to have been at a premium at the time, so it is perhaps understandable that club officials may have looked further afield for a bit more security, even despite the strong links with the city’s Irish immigrant community and strong local support.

“I suspect a number of Hibs fans will not be fully aware of just how close the club came to relocating in the early 1900s and, were it not for the combined resistance of the three clubs in Aberdeen, that move could well have come about.

“Had the relocation efforts been successful, it is likely it would have had a huge impact on the Scottish football landscape. What of the Edinburgh derby (with Hearts), or the Famous Five or even The Proclaimers and Sunshine on Leith?

“It probably doesn’t best part thinking about for some supporters, but the fact that the proposed moves to Aberdeen or even just along the road to Northfield didn’t come to fruition and likely forced officials into a rethink may well have helped lay the groundwork for the long-term existence of the club and the success of the 1940s and 1950s.”

Even at this distance, it’s clear that George Alexander, the hard-working and dedicated secretary of Orion, was one of the most important figures, not only in steering the different Aberdeen organisations towards a common goal, but in ensuring that their complacency did not allow Hibs to advance with their early discussions.

Amalgamation

Chris Gavin, the secretary of the AFC Heritage Trust, said: “Mr Alexander made the observation that the rumour (of Hibs relocating) was something of ‘a hardy annual’, but warned that it might turn to hard fact if local football legislators did not waken up to the threat and push forward with amalgamation.

“He reasoned that, as had already happened in Dundee, smaller senior clubs would soon be killed off by the presence of a top-flight club in the city.”

This redoubtable fellow, Alexander, was no shrinking violet. He could see the way the wind was blowing and made it his mission to deal head-on with what was described, rather melodramatically, as “the Hibernian question”.

He submitted a passionate case for the merger of the different Aberdeen organisations in a letter to the Evening Express in 1902, where he urged local legislators “with a genuine interest in bringing top-level football to the city to amalgamate and retain local control of the game rather than let outsiders capitalise on the opportunity”.

As we are all now aware, his campaign flourished and he helped transform attitudes at the grassroots in his home city. In a matter of months, the drive for different teams to pool their resources was successful and, in 1903, the present-day Aberdeen FC was formed.

Eddie Turnbull

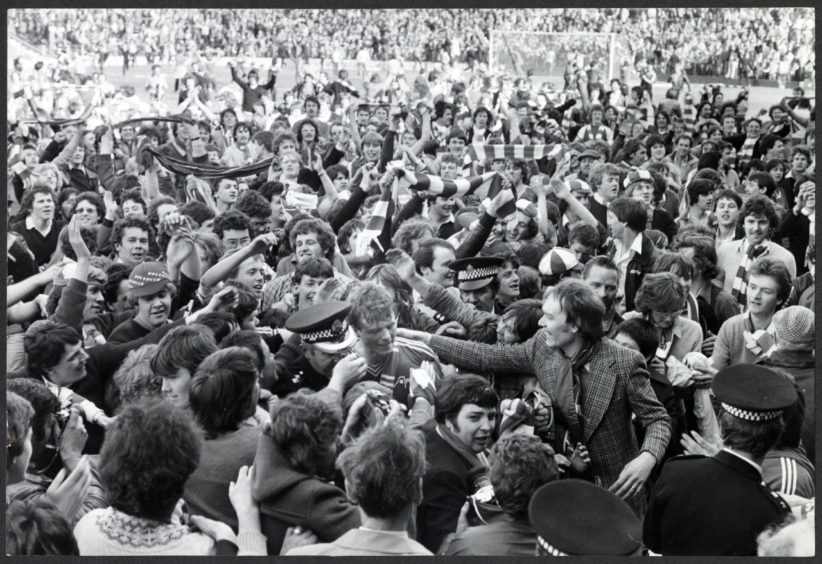

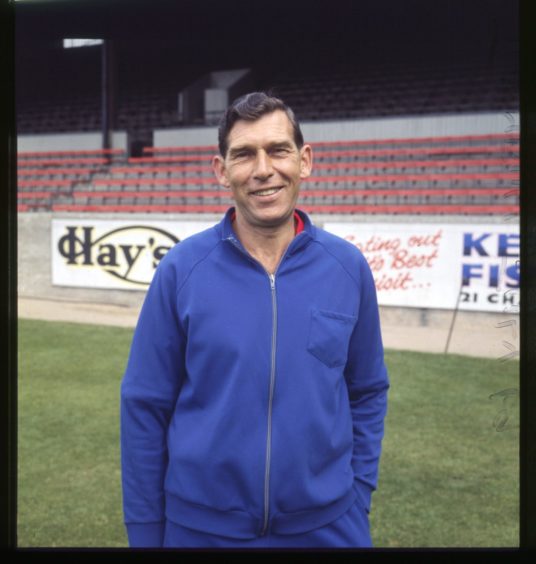

There has been plenty of movement between the two clubs in the intervening period. One only has to think about the exploits of such rugged characters as Eddie Turnbull, a stalwart member of the aforementioned Famous Five, who was the Aberdeen manager between 1965 and 1971 and steered the Dons to glory in the Scottish Cup in 1970.

Or Pat Stanton, the prodigiously talented Scotland internationalist who dazzled for Hibs on the pitch and was assistant to Alex Ferguson at Pittodrie off it.

Indeed, there have been a long list of other distinguished players with a link to both organisations, including Steve Archibald, and Gordon Strachan who was a fervent Hibs fan in his youth before becoming one of the Gothenburg Greats under Ferguson in the 1980s.

Ultimately, football developed at a rapid rate in these early years of the 20th century. But Hibs were clearly ahead of the curve in expanding their operations.

As Jock Gardiner, a trustee of the AFCHT, revealed: “Fortunately, George Alexander’s pleas paid dividends. But there is one interesting postscript to the story.

“That is in the fact that Hibernian, the recently-crowned Scottish champions, made a visit to Central Park in Kittybrewster (in Aberdeen) on May 13 1903 and drew 2-2 with Victoria United in what was the Vics’ last-ever match.”

It was the dawn – or should that be Don? – of a bigger, grander club in the city.