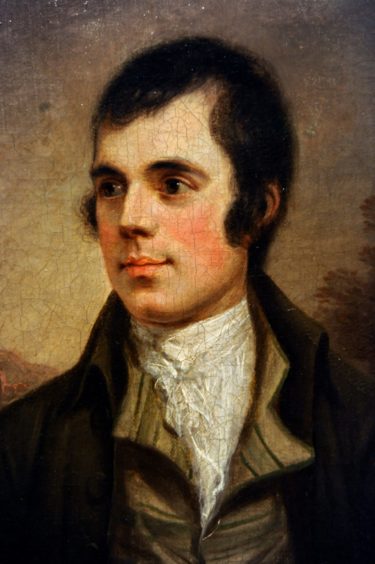

Robert Burns’ words are known and loved the world over… but did Rabbie speak with a Doric accent?

The idea our Bard might have used the north-east tongue of his Mearns-born father certainly caught the imagination of early experts delving into Burns’ roots.

Writing in the Aberdeen Weekly Journal in January 1915, James Crabb Watt KC, author of a History of the Mearns, described Burns’ father, William, as a man of culture and intelligence, although a “horny-handed son of toil”.

He added: “Old Burns carried the couthie Mearns tongue with him to Ayr and doubtless imparted a Mearns colouring to his son’s speech as well as thoroughness to his knowledge of Scotch customs.”

He would have used north-east words

And in 1927, a treatise on the Mearns accent in the Press & Journal by an author, bylined only as RHC, added to the argument for a Doric Burns.

“The father of Robert Burns carried his Mearns accent with him when he went south to Ayrshire and possibly the poet himself spoke with a Mearns accent,” he stated.

It is a tantalising prospect that the world will this Burns Night celebrate a world-figure who might have been “spikkin Doric”.

From Doric to Dundonian: Hear all the different dialects of Scotland

And it is certainly a possibility, said Douglas Samways, the president of the Stonehaven (Fatherland) Burns Club.

“I would definitely think he would have used Mearns and north-east words and phrases,” said Douglas, adding Burns’ farming family had roots running deep in the rich land around Stonehaven and Glenbervie.

William Burnes, was born at Clochnahill in the parish of Dunnottar in 1721, before leaving the family farm for Edinburgh in the 1740s and eventually to become a tenant farmer in Alloway in Ayrshire – where the story of Robert Burns begins after his father met and married Agnes Broun, whose family were Ayrshire farmers.

Whether he imparted his accent to his son will forever be uncertain, but Douglas is sure he passed on the rich cultural traditions of the Mearns, in songs and stories, to young Robert who would later go on to find and record traditional Scottish songs and ballads.

Songs from the past, sung by his dad

Douglas said: “I have no doubt that round the fire in the cottage in Alloway there would have been songs from the past, sung by his dad. That would have given him an insight into the Scottish culture that certainly his father was brought up in, but his mother as well.”

“And perhaps he thought it is time to record these sort of things. And if he hadn’t done, we would not have had Auld Lang Syne, for example.”

It’s an assessment which the historian Crabb Watt shared. Giving an address to the Aberdeen Burns Club at its Burns Supper in 1902, he said William Burnes took the tales of the north-east to Alloway with him, along with his accent.

“The customs and superstitions that (abound) in the works of Burns were the customs, tales, superstitions and legends of the Mearns,” he said.

But more than folklore, William Burnes – he never dropped the “E” although Robert did – gave his son another invaluable gift rooted in the Mearns way of life, said Douglas.

“His father, certainly, was a great believer in education. It’s a myth Burns was the uneducated ploughman poet, he certainly promoted that myth himself, he was a bit of a self-publicist at times and did a pretty good job of it.

Burns knew the classics

“He was well-educated. He did know the classics very well. If you read his works in English, he is clearly a well-read man. That could well have come from the influence of his father, who was influenced by his upbringing here, that strong sense of the importance of education, the sense of community and family, which are still alive in this part of the world.

“He also instilled that keen sense of fairness and equality that speaks loudly all through Burns’ works.”

Douglas said the Stonehaven (Fatherland) Club is fiercely proud of Burns’ strong links to the area, with his family having farmed here for generations, with some accounts putting them back to the time of Robert The Bruce.

The club has a walking tour, with details online, to take in many of the spots linked with Burns. It includes farms, such as Clochnahill, marked with a cairn at the side of the A90, as well as cemeteries where Burns forebears and relatives are buried, such as Glenbervie and Kirkton of Fetterreso.

There is also a Burns Memorial Garden in the heart of Stonehaven.

There are plans afoot to use that green spot, at the foot of Belmont Brae, as a means of telling people more about the Bard and his association with Stonehaven, such as introducing QR codes to open rich online content. That could possibly include stirring recitals of works such as Tam O’ Shanter.

Douglas said highlighting the connection between Burns and the Mearns is a vital part of the Stonehaven club – as is promoting Burns himself, even in the face of some negative attitudes by those who view him as parochial.

World-figures influenced by words

“A lot of people see him as just a Scottish poet speaking in these strange words. When you point out his reputation is worldwide they are really surprised. I think that’s a failure of the education system in Scotland.”

Douglas said Burns has influenced some of the most famous figures in history and literature.

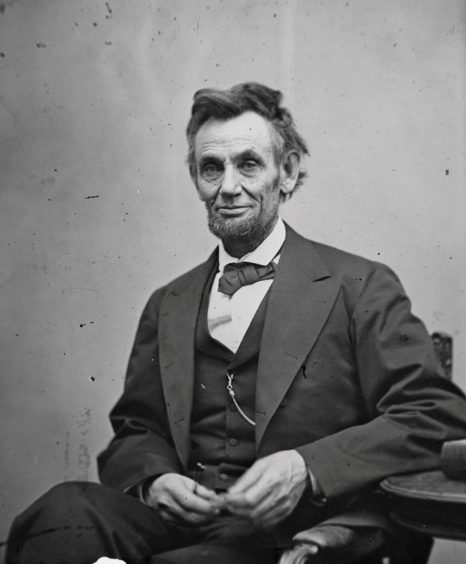

“The story is that Abraham Lincoln had two books either on his desk or beside his bed. One of them was his bible, the other one was the works of Robert Burns,” he said.

“Maya Angelou knew about him and his works. The more you look into it, the more you see there are people of that kind of standing who are influenced by the works of Robert Burns.”

It is fitting then, that Amanda Gorman, the young poet who created a worldwide sensation with her work The Hill We Climb at President Joe Biden’s inauguration was wearing a ring which once belonged to Angelou.

Others to have cited Burns as an influence range from Bob Dylan to John Steinbeck.

While William Burnes never returned to the Mearns, his son did, as part of a tour taking in swathes of the north-east of Scotland in 1787. He was at the height of his fame and was being lauded by the great and good as he made his way around the country in what some academics have called his “rock star” tour.

He spent a short time in Stonehaven – just a night, visiting a cousin who lived in the High Street, said Douglas.

Burns noted the meeting in his journal. He said. “Near Stonehive, the coast a good deal romantic. Meet my relations. Robert Burnes, writer in Stonehive, one of those who love fun, a gill, a punning joke, and have not a bad heart – his wife, a sweet, hospitable body, without any affectation of what is called town breeding.”

These are universal themes

The poet never returned to the Mearns. He passed away at the age of just 37 on July 21 1796, but had been suffering from ill health for at least five years before that.

But he lives on in his poetry and songs, the ideals he embraced and his powerful message about humanity and the human condition are as pertinent today as ever.

Douglas said: “That’s why he has lasted so long, these are universal themes he’s on about. If he hadn’t done that, he would have been an 18th century poet of some interest to some people but not very important worldwide.

“Look at A Man’s A Man for A’ That, for one of them. Then his Holy Willie’s Prayer about hypocrisy. Love is a universal theme and he has plenty of poems on that subject.”

No doubt that will be reflected in the Burns Suppers taking place online across the globe over this weekend and on January 25 itself, when glasses are raised to the Immortal Memory of a man… one moulded by the Mearns.

Burns and his visit to the ‘lazy town’ of Aberdeen

The Means wasn’t the only stop on Robert Burns’ “rock star” tour of the north-east of Scotland.

He also spent a night in Aberdeen – describing it as a “lazy town” but not expanding further.

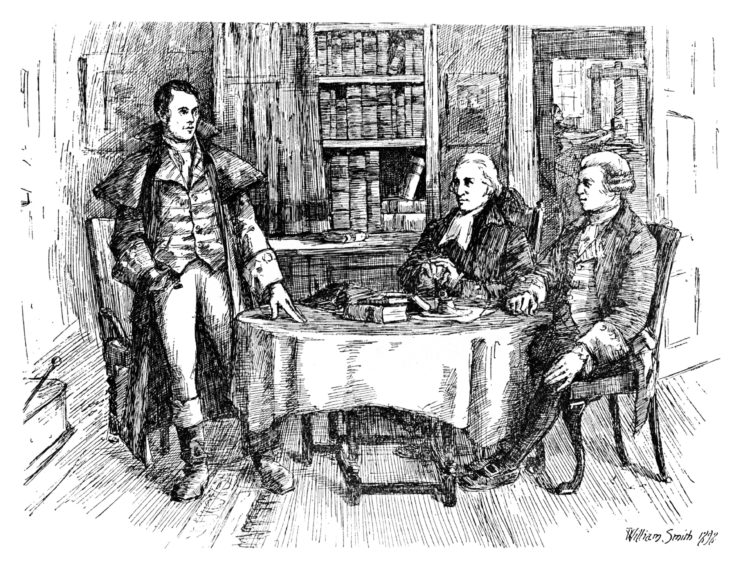

While in the Granite City, he met James Chalmers, printer and later editor of the Aberdeen Journal, the forerunner of the P&J, visiting the paper’s offices then in the Castle Street. There’s no record of what was discussed, other than Burns’ own description of Chalmers as a “facetious fellow”. Bishop John Skinner was also at the meeting, and Burns marked his “mild and venerable manner”.

As for the Burns visit to Aberdeen, it was merely noted in the Journal as “11th September 1787 – Yesterday passed through this place, on his return from a tour in the north, Mr Burns, the celebrated Ayrshire bard.”

City took Burns to its heart

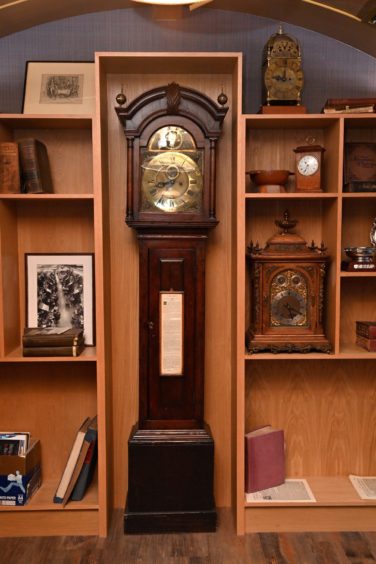

Today’s Aberdeen Journal offices at Marischal Square still contain a grandfather clock said to have been in the original offices at the time of the poet’s visit. A plaque on it reads: “We may speculate that the National Bard observed it ticking away the valuable moments at the memorable interview he had with the then Editor.”

While he might not have taken to the “lazy town” and his visit was virtually unremarked, the Granite City later took Burns to its heart. His iconic statue on Union Terrace was paid for by public subscription and a massive crowd flocked to its unveiling in September 1892.

Burns’ visit was part of a trip around the region he undertook with his friend, William Nicol.

On their travels they met the great and the good, including the Duchess of Gordon and the Duke and Duchess of Atholl.

Interest in Stuart monarchs

Other stop-offs included Inverness, Urquhart Castle, Cawdor Castle and Culloden, as well as visiting Forres, Elgin, Cullen, Banff, including Duff House where they were shown round, with Burns taking a particular interest in portraits of Stuart monarchs.

At Ellon they were knocked back after hoping to meet George Gordon, the third earl of Aberdeen.

South though Stonehaven and the Mearns, they carried on to Auchmithie then sailed along the coast to Arbroath before travelling on to Dundee, then on to Perth.

By the time they returned to Edinburgh, they had covered about 600 miles.

Along the way Burns collected fragments of songs and tunes, making new friends and also building contacts with the great, the good and potentially wealthy patrons.