It’s a familiar Hollywood plotline; the single-minded individual who confronts obstacles, struggles with strangers and ends up being tossed on to the scrap heap, but keeps fighting to bring their dream to fruition.

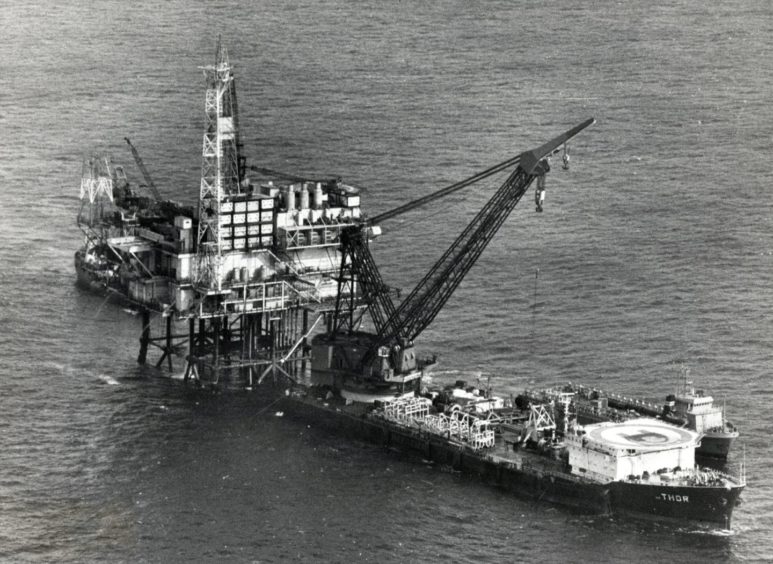

In the movies, there is usually a happy ending for such characters, but Tabitha Lasley wasn’t dealing in fiction when she moved to Aberdeen in 2015 to investigate the lives of the thousands of men who ply their trade on the giant oil installations, which have been at the heart of the north-east economy for nearly half a century.

On the contrary, the former London property journalist had just been through a messy break-up with a former lover, crashed into a brick wall in getting any help for the project from the oil companies – “They are allergic to journalists” – and eventually decided that, if she couldn’t talk to workers with their bosses’ approval, she would travel to Aberdeen and speak to them when they were in bars, clubs and casinos – on the ran-dan, off the leash, and yet all of it on a strictly confidential basis.

Men all at sea and women waiting back home

It has been a long journey from her time in the Granite City to the publication of Sea State, but the early rave reviews speak for themselves in explaining how Tabitha has managed to transform what could have been a tepid series of interviews with the oil fraternity into a compelling, visceral and very personal memoir where laddish bravado and testosterone clash with the author’s ingrained passion for her subject.

The picture which emerges is of a solitary culture, both for the men who journey to the marine hulks, called Brent or Bravo or Ninian or Trent, for weeks on end, while their wives, girlfriends and partners, who remain in the city, are often left looking after children, trying to combine jobs with education and balancing the books.

This schism creates its own tensions and Tabitha found herself in the middle of a messy romantic liaison even as she was investigating the industry by speaking to more than 100 oil workers, some Scottish, some Asian, some from the north of England, where in the old days, they would previously have worked in the pits or steel mines.

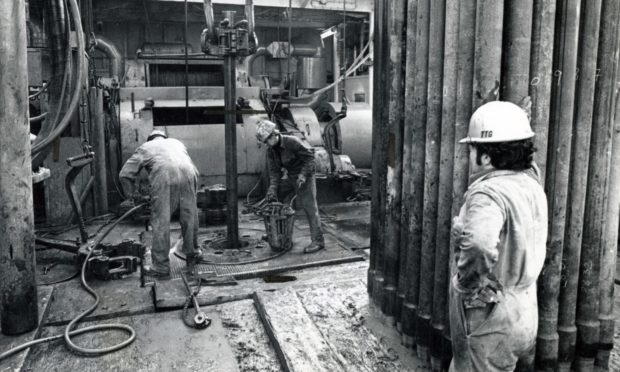

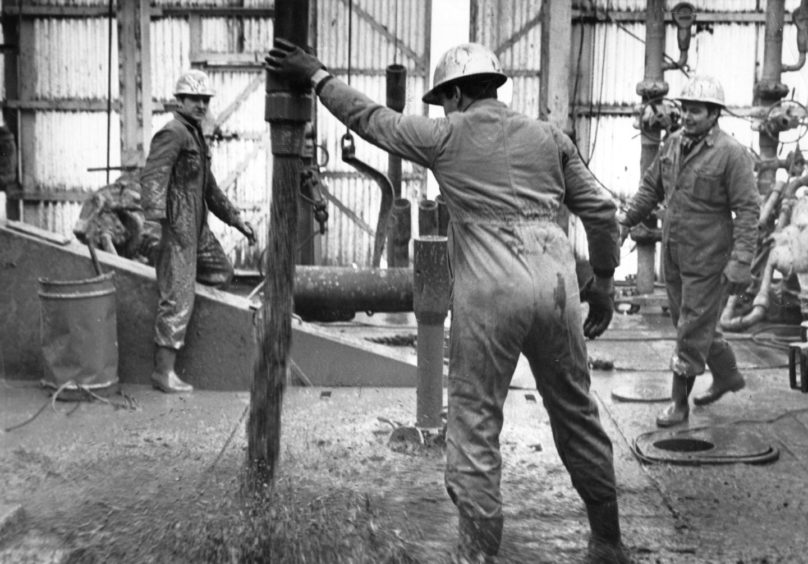

And, as she soon discovered, the world of riggers, roustabouts and roughnecks is a man’s domain with some very old-fashioned attitudes.

All the guys together brought out the worst in them

She recalled: “I didn’t know what I was expecting when I came up to Aberdeen, but it was one those situations where I realised I would have to go out and find people who were willing to talk to me about working on oil and being offshore.

“Many of the people were quite happy to chat and I learned a lot about the industry, the terminology and the shift patterns and how the men came back from the rigs wanting to let their hair down and, often, that meant heading straight to the pub.

“Right from the start, I was interested in examining how so many men coped with being in a restricted environment, and I heard so many stories about arguments and fall-outs and people being depressed and how private grudges were built up over many years.

“There was a tale of somebody who reached the end of their tether, filled their pockets with tools and threw themselves off the side. That became a recurring story. Some viewed it as an urban myth, others had alternative versions. So I had to learn to trust my instincts and inveigle myself into their company. One man told me he had killed another man. Heaven knows why you would boast about such a thing to a stranger.

“But Aberdeen is a relatively small city. Sometimes, you would bump into the same people, so I had to be careful. I only ever walked away from one interview because I felt it was moving in a bad direction. But there were other times where I could see the influence of so many men being together: it was like a prison or an army barracks or a football crowd. A place where women were routinely described as “slags” or “sluts” or worse. I hadn’t heard these words since I was at school, but here they were again.

“I’ve tried not to generalise. I met a lot of kind, generous people while I was living in Aberdeen, despite my friends asking me: ‘What are you actually doing up there?’

“But a lot of things were a shock to the system. When I spoke to union leaders, they were worried that safety would always come after profits. And, in a downturn, the pressure would increase on workers to cut corners. It was complicated.”

The poignancy of the Piper Alpha survivor….

Tabitha’s work features myriad different emotions and illuminates the apprehension which is felt by so many females as they witness the army of helicopters flying off into the distance every few weeks.

But sometimes, the most basic, unvarnished anecdotes pack the biggest punch.

One of her interviewees told her: “I once shared a room with a rigger who was on Piper Alpha [which exploded with the death of 167 men on July 6 1988].

“He was up on the helideck, the heat was burning his hair, but he was feart to jump. There was an older guy, trying to will him on, but he wouldn’t do it. So the old guy ended up grabbing hold of him and jumping.

“When they hit the water, the old guy’s life jacket came up, broke his neck, and he died. The lad told me this after we had been sharing a room for about a week.

“He still seemed very affected by it [more than 25 years later]. He didn’t speak much, he didn’t socialise, he didn’t really leave his room.

“He just stayed in there, reading.”

Women on the rigs were eyed ‘like another species’

Tabitha had refused to be judgmental about the men she met. In some cases, their words and actions spoke through a megaphone without her reinforcing the message: there were braggarts, boors, Boys Toys lovers and ostentatious splurgers, one of whom wasn’t happy unless he changed his designer trainers the way others change their socks.

But there were also mercurial souls, sensitive individuals, people leading hard-working lives with a refusal to let the grim atmosphere on the installations grind them down.

As for women and rigs, they usually belong in entirely different worlds.

Another interviewee told her: “There was one girl who came out to our rig. She was only nineteen. One night, she was playing pool in the rec room.

“She was wearing hot pants. Word got round and the rec room started filling up. And up. And up. Soon, it seemed like every lad on the rig was in that room, sitting there watching her play pool.

“She didn’t get disciplined, she hadn’t done anything wrong, but her supervisor did.

“They said: ‘You should have told her, you should have let her know she can’t do that here. That was your job, to tell her that, and you didn’t do it.

“As for the girl, she never came back [to the rig].

“That was her first trip off shore. And her last.”

Winners and losers in the oil industry

Tabitha hasn’t reached any grandiose psychological or political conclusions in Sea State. The details stack up, gradually, inexorably emphasising the often complex symbiosis between those who man the rigs in the blue yonder and their interaction with others.

Aberdeen emerges as a community of contradictions, a city “created from Louisiana avarice and Protestant thrift”, with both tremendous wealth and abject poverty.

And while it’s recognised nobody makes the riggers work offshore, or forces others to fall in love with them, these pages reveal that many couples find it difficult to navigate a path through uncharted territory in searching for an offshore/onshore balance.

Tabitha said: “The book’s real subject is money, and the way a person with money can exert control over his or her surroundings. The women in the book – and I’m including myself in this – suffer from a lack of money, and a concomitant lack of control.

“It’s a dynamic I saw over and over again while working on the book: the more money a man earned, the more he thought he should be inoculated from criticism, and the less agency his partner had. High earning men often think they can do as they please, and to a certain extent, they are right.”

It’s a fairly bleak assessment, but those promoting STEM subjects in science, technology, engineering and mathematics, have their work cut out and particularly given the thousands of jobs which have been lost in the North Sea in recent years.

Tabitha is now working on a new book – about contagion

When Tabitha left Aberdeen with all the interviews carried out and copious material in her laptop, she needed to find a job to pay the bills and eventually ended up working in a chicken takeaway restaurant in Ellesmere Port, near Liverpool.

There was nothing glamorous about that role, nor the many months she spent in the library bringing Sea State to fruition as she immersed herself in the project.

She recalled: “I wanted to make it as authentic as possible and let the men speak for themselves, but I was also determined to put it into the bigger picture of what was happening to so many women and families in Aberdeen.

“I changed my identity and my name when I met some of the people in the book. I was able to do to that because there are so many people coming in and out of the city and it is a minimal space. It has been years since I talked to these men.

“But I doubt very much that things will have changed since then.”

Tabitha is currently working on another book – a novel this time – about a hysterical contagion at a girl’s school, set in the 1990s. She doesn’t know when it will be finished and admitted: “I don’t get these things done quickly.”

But, on the evidence of her debut work, it will be well worth the wait.

“Sea State” was published this month by 4th Estate.