It was a story that remained untold and classified for more than 50 years after the end of the Second World War.

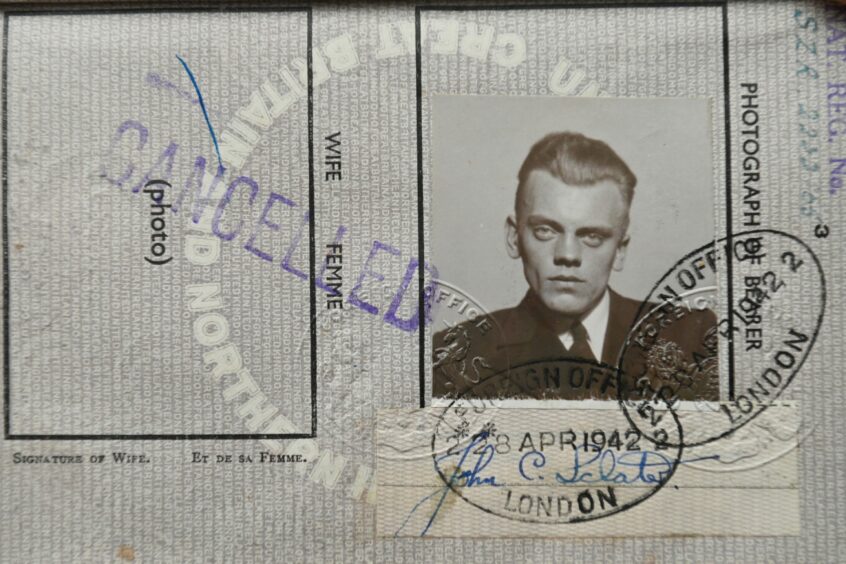

And although Elizabeth Copp knew her father, John Sclater, had served in the Merchant Navy as a radio engineer and been involved in the conflict, he never spoke about his experiences other than in the vaguest terms.

So it was with a sense of horror and astonishment that she and her sister, Eileen, discovered letters from her late dad while they were clearing their parents’ house in Orkney after the death of their mother in 1998.

These revealed that John had been among the survivors from the sinking of the HMT Rohna in the Bay of Bougie in the Mediterranean in 1943: a catastrophe that caused one of the greatest losses of life in US naval history.

The 22-year-old Orcadian had endured unimaginable privations after the destruction of the vessel, which led to between 1,130 and 1,150 young men being killed and more than 800 others struggling to survive, even as they were strafed by German planes while they were in oil-soaked water.

In anybody’s terms, it was a disaster and those who lived were threatened with court martial if they revealed any details about it.

The censorship went so far that the Rohna’s fate was covered up, even after the end of the conflict, and journalists in the 1960s were refused access to the files.

Now, though, a documentary is being made about the incident by US film director Jack Ballo.

He believes “it’s time to tell the truth” about the sickening events which destroyed so many lives in November 78 years ago.

And Elizabeth is glad that finally, belatedly, the appalling circumstances in which so many men perished are being highlighted in Remembrance Week.

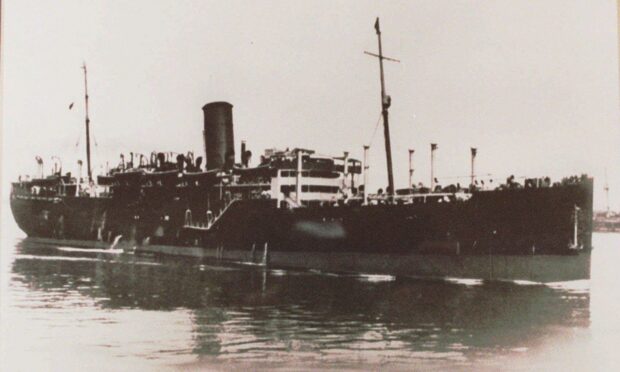

HMT Rohna was not fit for purpose

It was on November 25 – America’s Thanksgiving Day – that the British troopship sailed from Algeria, en route to Bombay, via the Suez Canal.

But should she still have been in service at all? As an elderly passenger ship, Rohna was only designed to carry 100 to 200 people, but on that fateful voyage, it had a crew of 195 Australian and British officers and Indian seamen and no fewer than 2,193 military men, most of them GIs who were squashed together like sardines in cramped and unsanitary conditions.

None of them were prepared for an aerial assault, but despite being part of a larger convoy, they were suddenly targeted by 35 German Heinkel planes from southern France, which were carrying two Henschel 293 guided bombs, the latest offensive technology pioneered by the Luftwaffe.

But when it came to the war and especially his time on the Rohna, he just wouldn’t talk about it.”

Elizabeth Copp

There was a sickening inevitability about the consequences when one of these formidable H293 missiles struck the Rohna on the port side, exploded in the engine room, and blew a massive hole in the starboard.

Chaos reigned amid the hellish pandemonium with some survivors later revealing the horrible extent of the injuries and criticising the inadequate equipment which led to some lifeboats and rafts being unusable.

The stricken crew, in their desperation, tried to cling on to wreckage or anything they could find which might provide support as they waited for assistance.

When the escort vessels arrived the following day, they discovered just a few men floating alive as far as 20 miles from the sinking.

Amid the carnage, more than 800 GIs simply disappeared forever.

John Sclater’s story gradually emerged

John Sclater was among those who was pulled from the water and he was convinced the Rohna had been torpedoed, such was the speed with which the vessel was torn apart in the conflagration and the confusion it caused.

He had done his training at Aberdeen Wireless College in 1941 when he was just 20, gaining his certificate in radiotelegraphy in October of that year, and then joined the Merchant Navy as a radio engineer.

He was posted to his first ship, the Dorington Court, just a month later.

He sent letters back to his parents in Orkney on a regular basis, but Elizabeth wasn’t aware of this correspondence until more than half a century later.

The story has gripped her ever since.

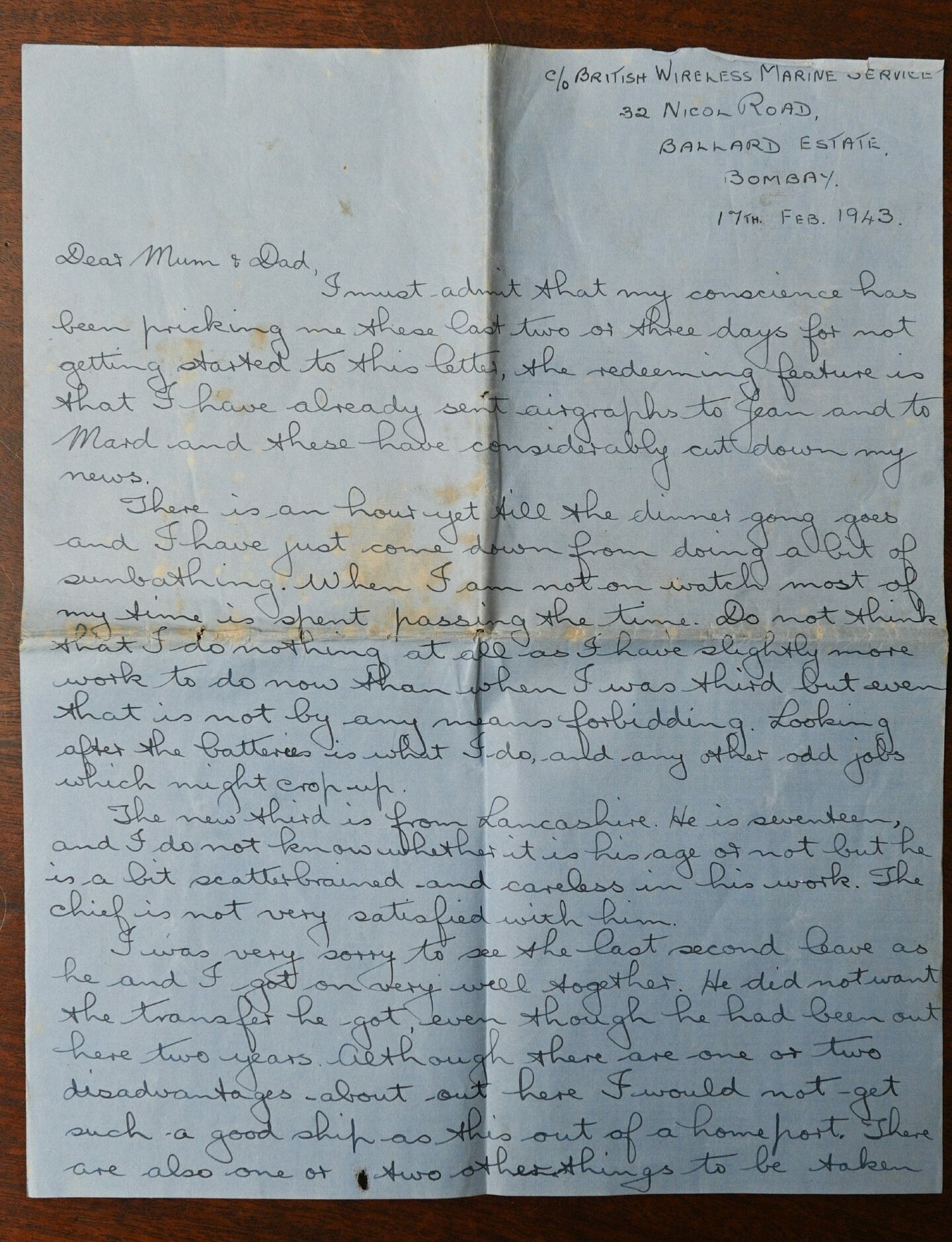

She said: “While he was in the Merchant Navy, he wrote to his parents and to his sisters, Jean and Mardi.

“Obviously, they were censored, but we did a lot of research into it and discovered that he had been on board the Rohna.

“I was horrified and, as the years have passed, I have tried to find out more information.

“I eventually tracked down a short film about it on YouTube and, at the end, there were a couple of email addresses.

“I wanted to find out if there were any other UK survivors and gradually learned more about it.

“It has been very emotional, because I recall dad talking about travelling to India and South Africa and other places and he enjoyed it.

“But, when it came to the war and especially his time on the Rohna, he just wouldn’t talk about it. Even after all this time, I’m not surprised.”

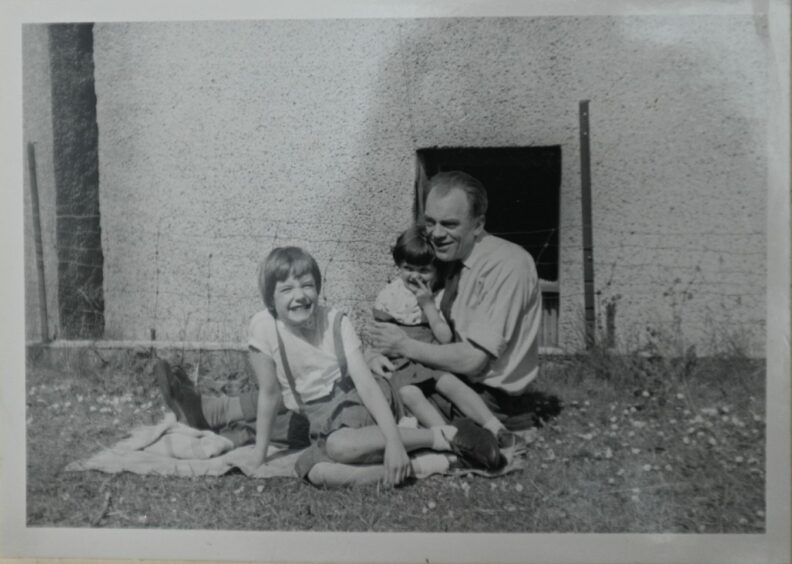

John Sclater contracted Type 1 diabetes during the war and although he wanted to remain in the navy, wasn’t healthy enough to continue.

But he did play his trade in the family business, Norsaga Tweed, which sold the handwoven fabric all over the world including sending supplies to the famous Brooks Brothers company in New York.

And while Elizabeth has moved from Orkney to Keith in Moray, she, too, has been involved in correspondence with colleagues in America on a regular basis since she started delving into the history of the doomed Rohna.

How could they have done that?

Even now, she can’t comprehend some aspects of the manner in which the vessel was reduced to a burned-out shell in such a short period and how the German forces could have maintained their attack amid the maelstrom.

She said: “I read a book by Carlton Jackson (Allied Secret: The Sinking of HMT Rohna) and it brought home to me just what these men went through.

“It was ghastly, because they were all young men, and so many died in horrific circumstances.

“I understand that in war, both sides are striving to destroy the other, but I can’t get past the fact that when the ship had been sunk, and all these poor souls were in the water, the planes kept attacking them.

“I mean, how could you do that to other human beings? You can’t gloss over what we are capable of, but I try not to become angry about it.

“It’s more a case that I am shocked, not only that so many people died on the Rohna, but also at how long we simply didn’t know it had even happened.”

It’s undeniable that there were concerted efforts by both British and American authorities to airbrush the Rohna out of the history books.

After all, they wouldn’t have wanted the wider world to know that the hapless, outdated vessel was sent into dangerous waters with insufficient lifeboats and safety equipment.

Yet, even with hindsight, Elizabeth believes it’s long overdue for the 1,000-plus men who died and their family and friends to have their sacrifice recognised and commemorated.

And, as she concluded: “Surely the blame must lie with those in the Ministry of Defence and War Ministry who decided that 2,000 men heading for Bombay – a long journey – could board a ship that was built for 200.”

Perhaps one can understand the subsequent cover-up by the authorities. But the whole story will be told in the forthcoming documentary.

She said: “My dad died in 1976 from lung cancer – he was only 55 – and I had no idea what he had experienced during the war.

“But he wasn’t the only Scot on board. I know there was a lad from Peterhead called James Alexander Welsh (a 35-year-old engineer) and he was killed.

“And there were others (including William McGowan from Glasgow, who was with the Royal Army Medical Corps).

“We are still discovering things about Rohna, even though this is something that took place nearly 80 years ago.

“I think we have to ensure that people don’t forget these men sacrificed themselves for the Allies and the scale of the losses was truly tragic.

“It’s the least we can do and especially at this time of Remembrance.”

Visit rohnaclassified.com for more details.