It’s 50 years this week since the first steps were taken towards transforming St Kilda into a dual World Heritage site.

That’s half a century since the decision by UNESCO to adopt a convention designed to preserve and protect a wide variety of global sites of unique interest.

And, following the establishment of that international treaty, St Kilda has gained global renown, both for its history and its remarkable natural environment and wildlife.

This was the remote archipelago where generations of redoubtable men and women defied the elements, the spartan conditions and being detached from their neighbours in the Western Isles and the rest of Scotland with a fierce commitment to self-sufficiency and creating an environment which sustained life for 5,000 years.

The population was never more than 2,000 at any time in its history despite the constant threat of disease. In 1684, an outbreak of leprosy afflicted the residents, then in 1724, a “contagious distemper”, thought to have been smallpox, ravaged their numbers and only four adults survived out of 24 families.

Because there were no spades at his disposal, one of the survivors is reported to have dug 11 graves with the back board of a wool card, which was only 18 inches by nine inches in size. It must have taken him days of endless toil. Yet, although the epidemic killed 17 heads of 21 families and left 26 orphans, the St Kildans endured.

A constant battle against nature

Eventually, though, as the population dwindled and the modern world impinged on their existence – whether in the influx of boatloads of tourists or the military personnel who began to regard St Kilda as an important strategic location – even the proudest residents began to accept they couldn’t continue their battle in the 20th Century.

And so it was that the countdown began to them being evacuated from their homes and offered opportunities elsewhere in the summer of 1930.

Norman John Gillies was among those who was born in St Kilda and grew up at the furthest point of the Outer Hebrides.

It lies a matter of 110 miles off the west coast of Scotland and is a place which, even today with access to modern sailing vessels, is not for the faint-hearted or those who suffer from the merest semblance of mal de mer.

In 1930, Mr Gillies’ family were among the last 36 people evacuated from the island, bringing two millennia of habitation to an end.

But although St Kilda has now acquired a mystical reputation – and it is one of the few UNESCO World Heritage sites for both its natural heritage and its marine environment – there was nothing romantic about the decision which was taken by the residents themselves to leave their roots 90 years ago.

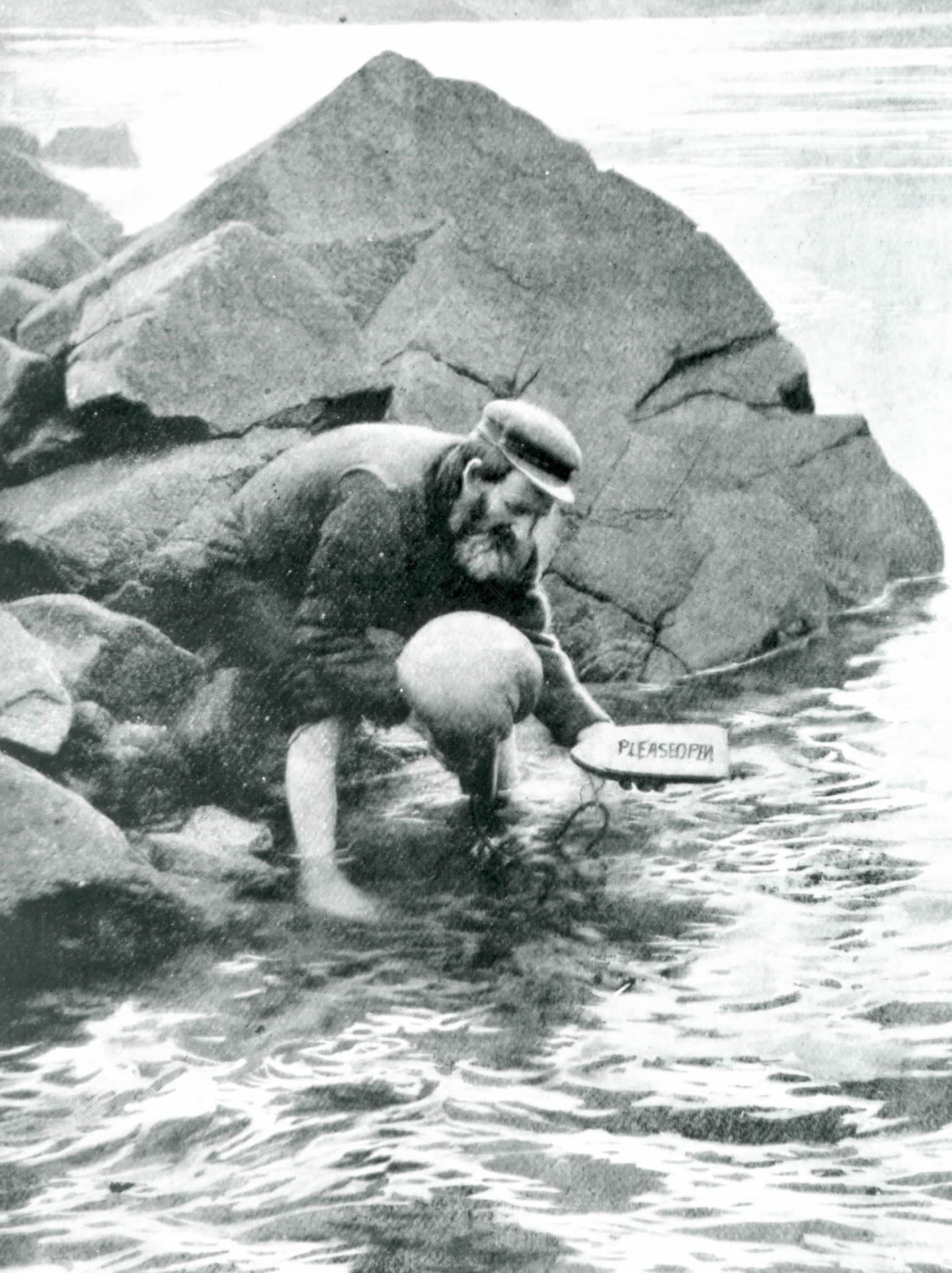

The loss of self-sufficiency began in the mid-19th Century when there was increasing contact with the outside world. From 1877, the SS Dunara Castle made regular summer cruises to St Kilda, and was subsequently joined by others such as the SS Hebrides.

The famous Aberdeen photographer George Washington Wilson was among those who highlighted the old-fashioned way of life which still existed among the islanders.

And, as the 20th Century arrived, the residents were introduced to new technological advances including cameras, automobiles, electric light and telecommunications.

John Ross, the schoolmaster, noted in 1889 that islanders spent time producing goods to sell to visitors, including sheepskins, tweeds, knitted gloves, stockings and scarves, eggs and ornithological items. But St Kilda was too remote to allow mass tourism, nor was there any reason to suppose it would have helped the indigenous population.

And while sons and daughters learned the old ways about how to catch birds and keep hunger at bay, there was a diminishing number to provide vital sustenance.

In 1912, for instance, the St Kildans suffered a number of acute food shortages and that was one of the catalysts for a serious outbreak of influenza the following year.

The Press and Journal reported: “The First World War brought a naval detachment to Hirta and regular deliveries of mail and food from naval supply vessels.

”When these services were withdrawn at the end of the war, feelings of isolation increased. There was more emigration of able-bodied young islanders and a breakdown of the island economy, which could not be stemmed by those who remained.”

St Kilda could ill afford to lose any able-bodied males. Already depleted by disease and emigration, by the 1920s the community was struggling to feed itself.

Nurse Williamina Barclay, who had been posted to Hirta, was horrified by what she found and as somebody who realised the limited medical service she could provide, she began her work to persuade the islanders, eight of whom were still of school age, that the time had come to leave their spiritual home.

It had already become clear that the majority of the islanders felt they could not continue life on St Kilda following the harsh winter of 1929-30.

The health of the islanders had long been a concern with the remoteness of the island brought into sharp view by the death of two women and a baby.

Mary Gillies, of 10 Main Street, who had been rushed to hospital in Glasgow, died of complications after giving birth to her daughter Annie, who also succumbed.

She was just 35. Then, shortly afterwards, another Mary Gillies perished at 14 Main Street from a form of tuberculosis, aged 22.

In these tragic circumstances, it was hardly surprising that on May 10 1930, 20 of the islanders petitioned the government for resettlement on the mainland, according to accounts held by the National Records of Scotland.

The departure of several men, whose tasks included tending sheep, weaving cloth and caring for the widows, meant ‘it would be impossible to stay another winter’.

The islanders added: “We do not ask to be settled together as a separate community, but in the meantime we would collectively be very grateful of assistance, and transference where there would be a better opportunity of securing our livelihood.”

The petition was also signed by Dugald Munro, the missionary and schoolteacher, and Nurse Barclay, who had been instrumental in organising it.

Yet while their efforts to secure the St Kildans’ future was based on humane reasons and in the residents’ best interests, the actual evacuation only took place after months of governmental discussions and anxieties expressed by some politicians and civil servants about the cost it would incur on the public purse.

There were few signs of sentiment on the morning of August 29, as people of different generations prepared for a seismic change in their lives.

Soon enough, all the houses were locked up and the properties left behind as HMS Harebell collected 13 men, 10 women and 13 children from Hirta, the largest island in the archipelago. By 8am, everybody was safely on board the ship as it sailed away from the residents’ long-time home which rapidly became a blur on the horizon.

Lieutenant-Commander Pomfret recalled the mood of the islanders in an account, which was later published by the St Kilda Club, and said: “Contrary to expectations, they had been very cheerful throughout, though they were obviously very tired.”

However, another account related how the residents looked back from their ship towards Hirta and described their abandoned home as being like “an open grave”.

The crossing from Village Bay took 12 hours with 28 residents coming ashore at Lochaline, in the Morvern peninsula, while others headed for Oban and on to Inverness, Portree and Stromeferry.

It was the end of a long goodbye

For these St Kilda residents, the months ahead offered many revelations – such as seeing a tree for the first time, catching sight of an automobile and listening to the radio. Many of the men went on to work in forestry with islanders impressing their new employers with their semaphore abilities and climbing skills.

On St Kilda, landowner Sir Reginald MacLeod received requests from people who wanted to move to the islands, but he declined.

He argued its time had come and gone and there was no possibility of continuing with a 19th Century existence as the rest of the world grew accustomed to mod cons.

Perhaps he was right, but the appeal of the archipelago lives on. And St Kilda remains one of the world’s most mesmerising places, boosted by its World Heritage status.

Conversation