In the end it took just four brief sentences to inform those on the front line that there really was to be an end to four and a half years of war.

At breakfast time on a fine, cold and misty day, the latest instruction to the troops was one they received with an unprecedented sense, if not of joy then at least of intense relief.

“Hostilities will cease at 11.00 today, November 11th,” the communique that pinged along the wires simply stated.

“Troops will stand fast on the line reached at that hour, which will be reported by wire to Advanced GHQ.

“Defensive precautions will be maintained. There will be no intercourse of any description with the enemy until the receipt of instructions from GHQ.”

The news would not have come as a surprise in itself, because personal accounts collated by the Imperial War Museum show soldiers were aware the war was drawing to a close.

But if evidence of a sweepstake within one unit that included guesses stretching out as far as the following Easter is to be believed, it may have arrived more swiftly than some dared hope.

Sooner than hoped maybe, but those short hours between the signing itself and the time set by the Allied leaders for the end of the fighting must still have felt interminably long.

For it was by no means just a question of waiting.

The carnage continued as the clock ticked down at the expense of 10,944 casualties and some 2,738 deaths.

George Ellison, a 40-year-old veteran from Leeds, was the last British soldier to pay the ultimate price on those battlefields, just four miles from where the first, John Parr, had fallen in 1914.

Their graves face each other at a military cemetery near Mons, in Belgium.

The silencing of the guns had been several months in the making, the wheels starting to move at speed in the August, when Germany’s military leaders accepted they could not win.

Hope remained for some kind of honourable “peace without victory”, which would see them retreating back behind their national borders, with an ability to rebuild, regroup and perhaps return stronger.

But as their Central Powers allies – Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire, Austria-Hungary – one by one signed armistice agreements, it became clear no such option would be allowed.

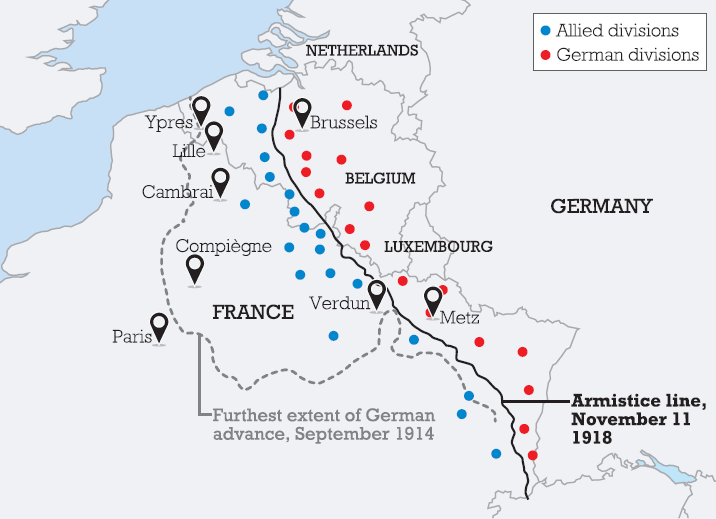

Beset by mutinies and revolts at home, on November 6 a meeting was requested and, 48 hours later, a German delegation arrived at a small forest clearing near Compiegne, France.

In the private railway carriage of the Supreme Allied Commander Marshal Foch, they were confronted with terms specifically designed to ensure the country could not restart fighting.

Clauses demanded they leave Belgium, France and Alsace-Lorraine, abandon military equipment and trains, allow the occupation of certain German cities by the Allies and return all prisoners of war.

Added to the mix was the need to make reparations – an element which would contribute to the rise of Hitler and a second world war.

On the evening before the deadline set on the eleventh hour, of the eleventh day of the eleventh month – with the Kaiser having abdicated and fled into exile in Holland – these terms were agreed.

Just after 5am, the papers were signed, leaving open that window for a final wave of death and destruction.

Once a silence did fall, it took until June of the next year, and three renewals of the armistice, finally to put a formal end to the war through the Treaty of Versailles.

Even then the situation remained so clearly fragile that Foch himself conceded it was not a peace treaty but a 20-year armistice – a period that would end in 1939.