Prince Harry’s encouraging message of “developing the best version of yourself” may have the opposite effect on some children, writes Helen Murray Taylor.

Horrifying statistics released recently from NHS England show unprecedented levels of mental ill health in children and young people.

For 17 to 19-year-olds, over a quarter are living with a probable mental disorder. The 2022 statistics for Scotland are not available, but trends from previous years suggest that the picture here is likely to be similar.

In the few months that I’ve been publicising my mental health memoir, I have been inundated with messages from people telling me about their own issues with mental illness but also, devastatingly, about those of their children. What is happening to our youngsters that so many of them are struggling?

It is certainly not that we have produced a generation of snowflakes. The causes of mental illness are complex. Socioeconomic and environmental factors play a much more significant role than has traditionally been recognised, with the most disadvantaged and marginalised kids in society at the highest risk.

It is hardly surprising that, with the cost of living crisis, the psychological legacy of the Covid pandemic, increases in online bullying and a reduction in available mental health services, 2022 was an exceptionally hard year for many.

Resilience is dependent on external factors

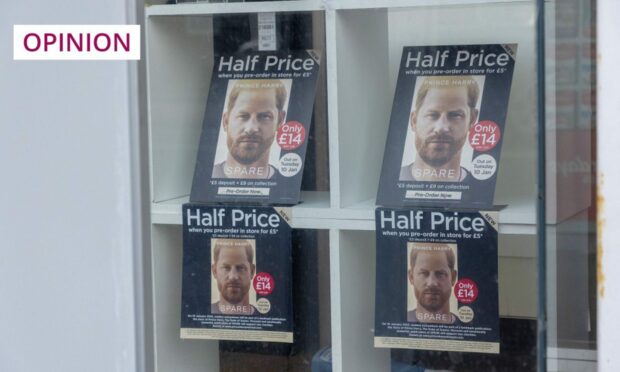

January 10 sees the official release of Prince Harry’s memoir. Whatever else is in the book, I expect there will be plenty of discussion about mental health.

Harry has been a fantastic champion in this area and should be applauded for the work he has done towards destigmatising mental illness. However, there are areas where I feel his message is misguided.

He seems to have bought into the idea that resilience is the key to “developing the best version of yourself”. He talks of keeping “mentally fit and not languishing”, but there is a danger that, rather than being inspiring, these words could have the opposite effect.

Spreading the message of resilience suggests that, with enough effort, we all have it in us to change our mental state. For a child who is struggling with mental illness, how can this idea – essentially to toughen up – do anything other than reinforce their feelings of worthlessness and failure?

It fails to acknowledge how dependent resilience is on external factors in our lives – strong social networks, healthy family relationships, good physical health, a safe environment to grow up in – things that not all our kids can rely on.

Viewing mental resilience as a trait that requires individual effort takes the onus off government and other agencies to tackle the societal issues like childhood poverty that underlie the shocking statistics. Increasing mental health awareness and encouraging healthy behaviours is all well and good, but will not, in itself, relieve this crisis. For that, we need fundamental social change.

Helen Murray Taylor is an author and former doctor

Conversation