One of my favourite ever newspaper cartoons is from back in 2012, and is by the Guardian’s Stephen Collins.

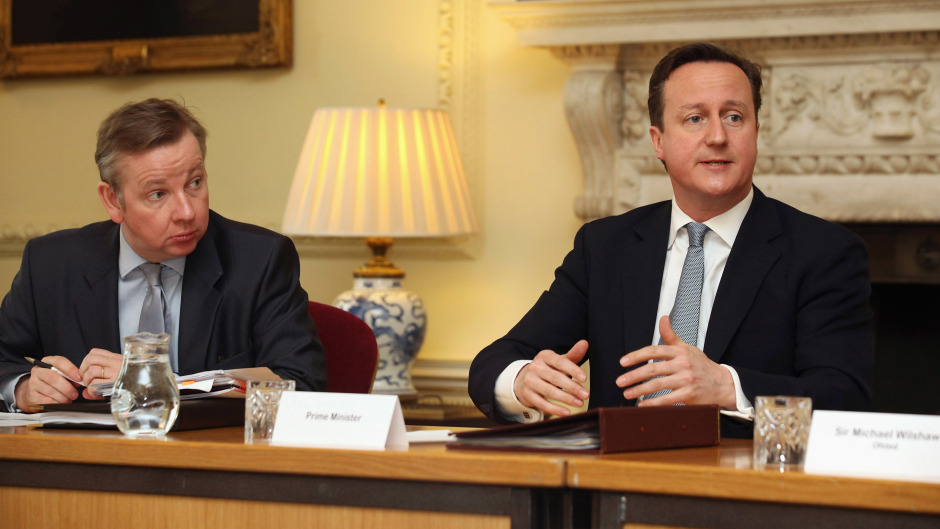

It shows a large, threatening alien spaceship looming over London. Prime Minister David Cameron looks nervously up at it from his Downing Street study.

Enter Michael Gove: “I know I could do it, David. I could fly a fighter plane into the big spaceship and shoot all the aliens. I used to be a journalist… I wrote two articles about planes… I’ve got strong opinions about aliens. I know I can do this job.”

The cartoon ends with Gove’s plane missing the alien craft entirely and wobbling off into the distance, leaving Cameron with his head in his hands.

It is a work of art: a perfect piercing of the cocky columnist who spits out opinions like bullets and seems always to believe they could do a better job than anyone else at pretty much anything. In particular, it is a warning about the dangers of unleashing blowhards like me on the complex reality of government and people’s everyday lives.

It is a work of art: a perfect piercing of the cocky columnist who spits out opinions like bullets and seems always to believe they could do a better job than anyone else at pretty much anything. In particular, it is a warning about the dangers of unleashing blowhards like me on the complex reality of government and people’s everyday lives.

That warning rings all too true after three years of Boris Johnson – another wizard of the op-ed pages – who, having made it to No 10, found himself wholly ill-equipped for the role. It turns out that typing things is not the same as getting things done. Who’d’ve thunk it?

Ok, Stephen Collins' Michael Gove cartoon is basically the best thing ever. pic.twitter.com/PL86ryrF

— The Poisonous Euros Atmosphere Fan (@DawnHFoster) January 26, 2013

Ironically, though, it is Gove who has gone on to show that this needn’t always be the case. For my money, he has been the most impressive minister of the past decade or so: a consistent intellectual light amid the guttering flame of Conservative credibility. Now that he has announced his departure from the front line, it seems like a good time to give him his due.

Gove’s principled stance cost him

It rather goes against social media’s passion for denunciation, but I don’t always have to agree with politicians to appreciate or respect them.

There have been plenty of issues over the years over which Gove and I have parted company – Brexit being the most seismic and obvious. But, even then, I never felt – as so many of us did with Johnson – that his support for leaving the EU was based on personal political calculation. In fact, Gove’s principled stance cost him: it ruined his relationship with his friend David Cameron.

There were also times where Gove and I were in concord. His determined pushing through of free schools and the expansion of the city academies project, in the face of ferocious opposition from the education establishment, has improved the exam results and the life chances of thousands of English children. If only a Scottish education minister had been so bold.

Sir David Bell, who was Gove’s permanent secretary in the Department for Education, praised his “legendary politeness”.

“He was very good with officials, he was open, he listened,” Sir David continued.

“He had a voracious appetite for reading and he was completely engaged with the agenda. That was something that impressed officials.

“Here was somebody who was absolutely on top of the brief and who was prepared to put the hours in. Michael was clearly up to it intellectually, and he worked enormously hard to drive his agenda.”

An intellectual and influential voice

“Up to it intellectually” is not an epithet much thrown at lightweight Tory ministers these days. But Gove showed again and again that he was the most effective player on the team, whether by introducing greater compassion into the criminal justice system while justice secretary, or working to reduce the amount of plastic used in society while at the Department of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

Gove’s was the most influential voice in getting rid of the boorish ‘muscular unionism’ that sought to impose Westminster policy and attitudes on devolved Scotland

When Covid hit, he urged Johnson to bring in lockdown sooner rather than risk hundreds of thousands of lives – a decision for which he is now battered by the libertarian right, for whom economics seems to trump humanity. Even on Brexit, he has sought to pull the government back from pursuing the kind of Singapore-on-Thames marketisation favoured by the blink-eyed extremists.

Gove’s was the most influential voice in getting rid of the boorish “muscular unionism” that sought to impose Westminster policy and attitudes on devolved Scotland, instead seeking to work constructively alongside Holyrood. The worrying comments emerging from Liz Truss and her outrider Lord Frost on Scotland suggest that this approach sadly may not outlast him.

We haven’t heard the last of him

Gove has shown he has the intelligence and the empathy to learn as he goes along and, when necessary, to change his mind. If you contrast this with, say, the unthinking belligerence of a Priti Patel, he is undoubtedly the superior and preferable politician.

He had initially backed Kemi Badenoch in the Tory leadership contest, attracted to her quick, sharp mind. At the weekend, he wrote that Rishi Sunak was his preferred option from the two remaining contenders, suggesting the platform put forward by Truss amounted to “a holiday from reality”.

“I do not expect to be in government again,” he added, perhaps unnecessarily.

He is still only 54, and so I doubt we’ve heard the last from him. And, if the aliens arrive, he’ll be ready to serve.

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank, Reform Scotland

Conversation