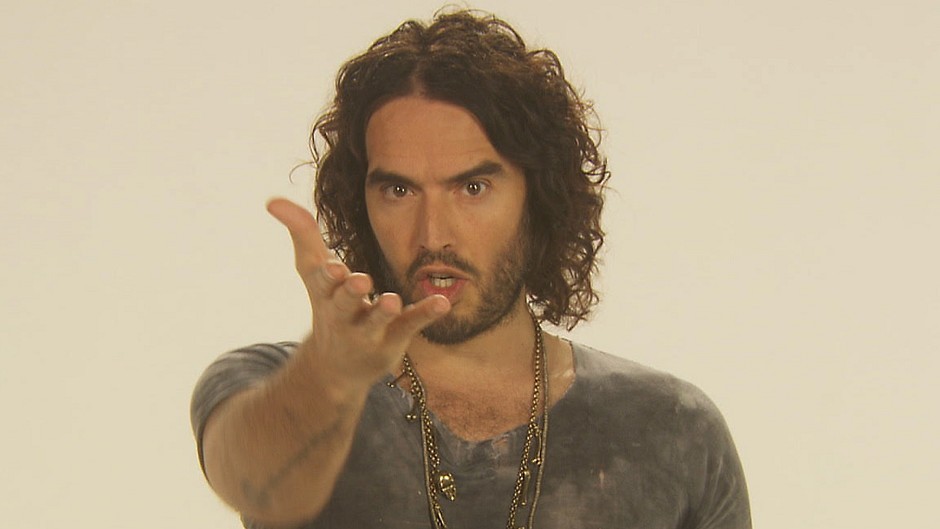

An old school friend was staying with me this weekend, when the allegations against Russell Brand surfaced.

The two of us grew up in Edinburgh and spent the summers of our late teens working in the service industry at Edinburgh Festival Fringe venues. I waited tables in the main cafe bar of one of what is now known as “the Big Four” – the venues with the biggest clout and ability to pull in star performers, especially from the comedy world. She sold hot dogs in the courtyard of another one just up the hill.

“Ah, so that’s who it was,” she said. “When we first heard it was a comedian, before they released his name, I thought it might be…” And she named another well-known comic whose stand-up career took off in the late 1990s, when we worked in those Fringe venues, and who made the move to mainstream television in the 2000s. “I was warned about him when I started the job, because I looked so young – I would be his type.”

I remembered that comedian walking through the bar I worked in, coat swishing across the floor, the crowds parting for him seemingly by the sheer force of his star power. Another memory: another comedian, this one already telly-famous and whose show I loved, grabbing my arm when I was sent over to ask him and his friends to stop throwing polystyrene aeroplanes at the waiting staff while we were carrying trays and plates. “Listen, sweetheart, I will drop my trousers and w*** all over you and all over this table if I so desire.” The message was pretty clear: I have power, you are nobody. Lucky to be here, and don’t you forget it.

We all knew where we stood in the pecking order

The thing was, it was exciting, that job – the glamour and proximity to celebrity. I’m not sure why else we went back; it couldn’t have been the wages or the hours, which were respectively insultingly pitiful and exhaustingly excessive.

Some of the young women I worked with (it was always young women in that job, the men’s applications mysteriously lost, perhaps) were very open about being there to have sex with comedians. And some of them probably had a great time doing it. Others didn’t, though.

There was the English 18-year-old, away from home for the first time, who I (as a local) had to take to the sexual health clinic after she was given herpes by a comedian who still came to our bar every night but blanked her after their encounter. There were always people crying in the staff toilets.

None of the young women I worked with would ever have even considered making a complaint about their treatment. Many women my age have reported reconsidering early sexual encounters we’d been led to believe were normal in the light of the Me Too movement; Gaby Hinsliff has written in The Guardian this week about the experience of being a woman fake-laughing at Brand’s comedy because you didn’t want to seem uncool.

We all knew where we stood in the pecking order compared to the “talent”: we were replaceable. At my venue, if you didn’t turn up for three unpaid days of painting the walls before the Fringe opened, you lost your “slot”. Not your “job” – your “slot”. Like it was an experience, rather than employment. Lucky to be there.

Pay is low, tempers fray and ‘open secrets’ emerge

I’ve been thinking about this a lot as I read through the Brand allegations. What sticks out for me even more than the horrendous testimonies is the way all the industry figures around him acknowledge that his alleged behaviour was enabled by the institutions he worked within.

There are stories of female crew being quietly moved off programmes he worked on. Audience members who he’d seduced being hushed up. One researcher remembers being told: “That’s just what happens with talent. Boys will be boys.”

The very idea that this behaviour had been “an open secret” within the comedy industry. An open secret. Known, not acted upon. I saw someone on Twitter suggesting that the only reason the allegations about Brand are surfacing now could be because he’s alienated all the people who used to make them go away.

The creative industries are held up by underpaid or sometimes even volunteer labour from people who are told they are lucky to be there, who internalise that

I’ve worked in the arts in Scotland for 20 years now – I’ve been lucky enough not to have been party to or victim of any “open secrets”, but I know people who have, and over the years I’ve sometimes noticed similar underlying conditions at play.

Often, organisations are putting events, productions, filming schedules or festivals together on shoestring budgets, with temporary staff and little or no HR management. Pay is usually low, and certainly not commensurate with the hours expected to be put in. Tempers often fray.

It’s all underpinning that same power imbalance; the creative industries are held up by underpaid or sometimes even volunteer labour from people who are told they are lucky to be there, who internalise that and subsume themselves under the understanding that the show must go on.

Kirstin Innes is the author of the novels Scabby Queen and Fishnet, and co-author of non-fiction book Brickwork: A Biography of the Arches