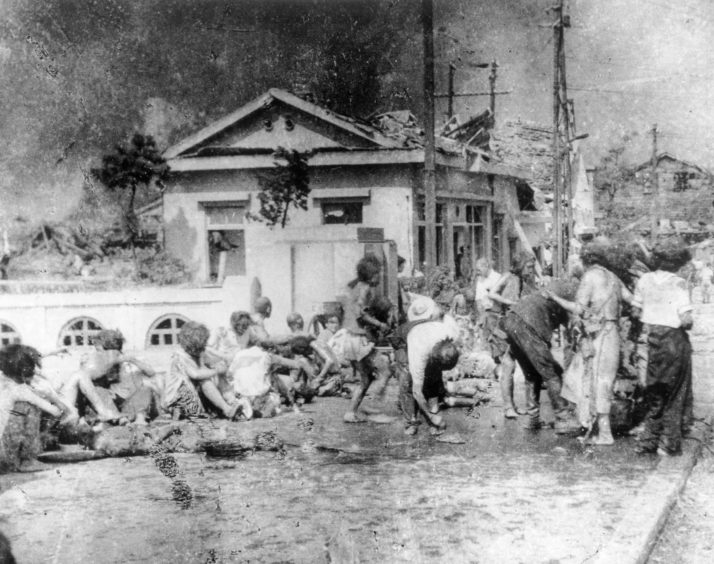

South-east Asia was hell on earth for the Black Watch as they fought to reclaim the land from the Japanese.

Men who later came out of the jungle would find that their stomachs had shrunk so much that all they could eat was soup.

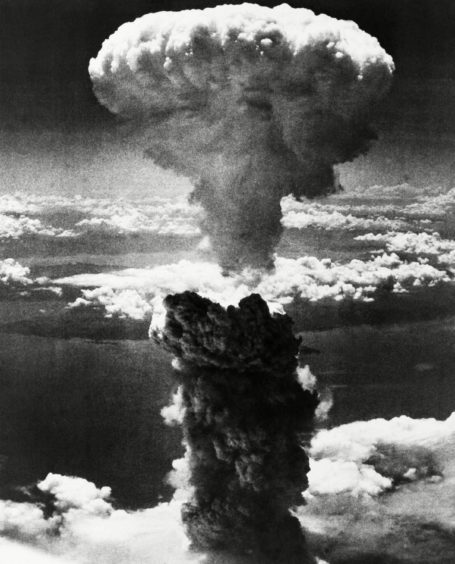

The dropping of atomic bombs on Japan brought the war to a sudden end.

Wednesday and Thursday were then announced as holidays to celebrate victory.

The 2nd Battalion celebrated by having a fun fair with elephant rides and pony racing and all sorts of side shows.

Every man was issued with three bottles of beer.

One half spent the evening at the Battalion concert which proved a great success while the other half held a sing-song.

The Battalion were still celebrating the following day with everyone in high spirits and there was another issue of two bottles of beer per man.

Private Edward Graves – transferred to The Black Watch from the Seaforth Highlanders in December 1944 – recalled in a diary entry how they were cheering, drinking and lighting bonfires after the war ended.

He said: “By now the news of the surrender of Japan had been announced.

“We first heard the news over the company ‘REC’ tent wireless, and the cheering soon spread as other company’s heard the long awaited news.

“That night the band toured the camp until about two in the morning.

“There was free beer and great bonfires were lighted.

“After a few days we settled down to our duties and in the afternoons education classes were started.

“Every day now the chaps who had been abroad a few years were going home and with the war over some were on demobilisation.

“At the time of writing now we are getting into peace time routine every day.

“Plenty of spit, polish, drill parades and ceremonial guards.”

In December 1941, Japan attacked British, Dutch and American territories in Asia and the Pacific.

By June 1942, Japanese conquests encompassed a vast area and prisoners of war and enslaved civilians were forced to work for their captors in harsh and often inhuman conditions.

A series of land battles were fought in China, Burma and New Guinea.

The fighting in Burma was brutal with all British servicemen severely challenged by the atrocious weather conditions in the malaria-ridden jungle.

Stuart Kennedy, curator at the Perth-based Black Watch Museum, said: “In December 1941 Japan attacked the British territories in Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore and Burma.

“The Japanese invasion of Burma in 1941 posed a deadly threat to British India.

“The 2nd Battalion arrived in India from the Middle East just as new tactics were being developed.

“In late 1943, the Battalion became part of the Chindits.

“They were trained to operate far behind enemy lines, attacking the Japanese supply routes.

“Once in position, the Chindits had to rely on aircraft for all their supplies.

“In March 1944 the Battalion, now divided into two columns of roughly 400 men each, was flown deep into Burma.

“Over the next few months they attacked Japanese forces diverting them away from the frontline.

“Losses in battle, extreme conditions and disease took their toll.

“When the two columns were finally withdrawn from the jungle in August 1944, only two officers and 48 men were judged fit for duty.

“Among the greatest problems was disease such as dysentery.

“Men who later came out of the jungle would find that their stomachs had shrunk so much that all they could eat was soup.

“The American K rations that they were given to survive on had little nutritional value.”

The rations came in waxed paper that could be used for starting a fire which in a wet jungle was very useful.

After the withdrawl of the Chindit expedition from Burma in August 1944, the Battalion was reinforced.

In November it was given a new role as part of the 44th (Indian) Airborne Division.

The Division was scheduled to take part in the planned invasion of Malaya in 1945.

However, the dropping of atomic bombs on Japan brought the war to a sudden end.

Private Andrew Meldrum had been serving his apprenticeship as a bricklayer and was working at Rosyth Naval Base when he was conscripted into The Black Watch.

His diary provided an insight into life on the front line against the Japanese.

“We were dispatched to Chittagong, in the Bay of Bengal from where we were able to move down into the war zone,” he said.

“The Jap strategy seemed to be part of a plan to capture the state of Manipur.

“Ranchi was in the hottest part of India being near the Equator and this was where we were transferred to.

“We were to be trained in jungle warfare and, by God, did we sweat!

“It was march, march, march until you were almost dropping but I’m glad to say that my feet never gave me any trouble as they had done in France.

“After we got ourselves fit by marching with full kit, 100 rounds of ammo, three grenades and one clip of our Bren gun, sticking to the rule of marching for fifty minutes and resting ten, we found that the platoon was really shaping up.

“We had instruction with the mules too, and it was pointed out to us that at each halt it was ‘see to your mules first then sit down’.

“My first view of Burma was just a mass of trees but we had a very good view of the jungle as we were flying in at tree-top height.

“One had the sensation of running along a green carpet, so close were we to the tree-tops.”

Private Meldrum told how he broke out in a cold sweat when there were listening posts and night defensive outposts to be manned.

“It was my turn on listening post,” he said.

“We were posted about twenty yards to the right of the column and were able to touch the man on our right.

“I didn’t relish this duty therefore in no time at all, I was breaking out in a cold sweat.

“There is nothing worse than being on guard, unable to see anything, just lying listening, straining your eyes by looking into the dense undergrowth which was as black as night.

“Suddenly there was a sound of movement behind me and, although it was only a patrol of West Africans going out, did I get a fright!

“When they returned the column was alerted as there was Japs snooping around.

“I have never been so glad to see daylight come in.”

Ex-Black Watch and Cameronians soldier Fred Patterson always believed what happened in the Far East was the ‘forgotten war’.

Signing up at Perth, the 18-year-old apprentice joiner from Blairgowrie was not the first Patterson to join the army.

His great-grandfather signed up to The Black Watch in 1853, before being incapacitated by a musket ball to the thigh during the Indian mutiny of 1856-58, while his father served with the 2nd Battalion The Black Watch during the First World War.

His family had been defending India since the 1850s but that did little to prepare him for the horrors that would await him in the deepest jungles of India and northern Burma.

It was March 1943 when, after initial training, Mr Patterson and around 2,000 other newly conscripted soldiers began their long journey to India aboard the converted Polish cruise liner the Sobieski.

He kept a diary all the way out to Bombay, recording the daily mileage, the ship’s position and the aircraft that were escorting them.

When he came off the ship in Durban, he realised what a small world it could be – discovering that at least one friend from back home had been on the ship in front of his.

Then, after seven weeks training, he was transferred to the 1st Battalion Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), and, so began, a difficult spell as a sniper, mortar and flame-thrower specialist in the jungle.

Mr Patterson suffered 22 bouts of malaria and had his hearing permanently damaged by shell-fire and anti-malarial drug treatment.

“They were looking for volunteers for long-range penetration, or LRP,” he said.

“We were on parade at night, north of Bombay and they were looking for 120 volunteers, but not a soul moved.

“Then it was taken out of our hands.

“The sergeant shouted ‘Three paces forward The Black Watch,’ so that was it.

“We were transferred to the Cameronians – we got our feet examined first of all, because it was going to be a hard life.”

The Lanark-based Cameronians were in the middle of a jungle exercise when he first arrived with them, but within minutes, he realised, despite losing his Black Watch title, he would not be losing ties with home.

“The monsoon had broken, and the first fella I met was this wee lad who comes in with a wireless on his back, hat hanging doon, the rain pouring off him,” he said.

“It was a young fella fae home in Blair.

“We stood and blethered for a while.

“‘Don’t go away,’ he said, ‘there’s another Blair lad coming up behind me’. It was my next door neighbour!’’

Training for LRP was tough and only 30 of them would last the pace and if you raised a blister within 16 miles you were out.

He said: “We would march through the jungle, learn all the jungle craft, blazing a trail, leaving tracks so you could find them, but cover your own tracks, that sort of thing.

“We learned that LRP meant going away far in behind the Japanese lines to disrupt enemy supply and communications.

“We would put in a static position with machine guns on a prominent feature near the road or railway so that we could control the Japanese, using ambush tactics.

“The other battalions would circle round to protect us from the Japanese.

“The problem was, there were only two brigades of the true Chindits (special force trained in commando methods to infiltrate behind the Japanese).

“The others hadn’t the training we had and this was a recipe for problems.

“We did training in the central province – the thickest jungle in India – and we got our rations cut down and cut down to a piece of bacon and two or three beans.

“It was so bad they put an armed guard on the four corners of the kitchen.

“It was getting to the stage where there was just about mutiny.

“That was all part of training.

“We weren’t allowed to smoke cigarettes because the enemy might smell them.

“Yet you could light fires because it went up through the trees.

“There was no talking for a month.

“Just hand signals, so there was no voice carrying.

“They would take us about 10 miles into the bush and you had to find your own way back to camp.

“That was a difficult thing, but I had a homing instinct like a pigeon.

“I always got back first, but some boys would take maybe two days.

“Other times we would go looking for the Japanese.

“If there was nobody there we’d put on a road block and shoot up the first trucks that came, and that could be pretty drastic.

“Almost every week ambushes like that would happen.

“One night I was walking down this unmade road in the pitch black when my mate put his hand across my chest, stopping me dead, and said ‘Do you feel anything?’

“I says ‘No, what is it?’

“He says ‘There’s a wire right across my neck’.

“There was wire that had been drawn right across the road and it was tight against his throat with a bomb at the end of it.

“If I’d hit it that was us.

“But that was the sort of thing you were up against.”

The fighting was bad enough but there was also malaria, dysentery, jaundice, foot rot, venereal disease, giant tree ants, leeches and ticks.

He recalled: “I had one right under my arm pit one day and it was irritating.

“I thought it was my webbing at first.

“We stopped in the middle of the afternoon and I took my webbing off, and here was this tick right in there.

“It had a big bellyful of blood in it.

“But this wee fella pulls out a newspaper, sets alight to it and within seconds it was out.

“Just as soon as he did that, he walked off, but this officer cleaning his hand grenade accidentally let the lever spring so he had no option but to throw the grenade.

“He threw it, it hit a tree, bounced back and killed the wee fella that had just taken the tick out my arm.

“It was sad and so pointless.

“But these are the sort of things that happened.”

The Japanese also thought they could fool the enemy by pretending to be Allied soldiers and they came through the jungle singing Loch Lomond.

“And I think, that’s not ours anyway, we don’t sing.

“So we knew this was the Japanese coming down.

“They came up the road in the same jungle green as we were wearing.

“They could have been mistaken for us anytime.

“But one thing we didn’t do was sing. They thought they could fool us.

“By this time my cover was blown and I had this shoot out, killing this Japanese soldier at close range.

“I had my 21st birthday getting my backside shot off. It was a hell of a nerve-wracking life!”

He was also present at one of the worst battles to take place in the whole operation – the siege of Blackpool.

Pinned down by the Japanese with no water and almost no ammunition, very few men made it out alive.

The men had to keep on the move, therefore the wounded could not be evacuated.

When the end of the war finally came, there was no official celebration to say it was over.

In fact, it would be around another 18 months, in April 1947, before many of the soldiers would get home.

Mr Patterson finally returned to Blairgowrie after three and a half years away, and resumed work as an apprentice joiner.

With the war in Europe having finished almost two years earlier, and not much public knowledge about the horrors of the Far East, he said it was frustrating trying to explain to people what he, and thousands of others, had been through.

He said: “Most of the focus was on what happened in Europe, but many of the things that happened out there were worse.

“I was young when I came back but I felt like an old man.”

Bernard Fergusson joined The Black Watch as Second Lieutenant in 1931.

In October 1943 he was promoted to acting brigadier and given command of the 16th Infantry Brigade, which was converted into a Chindit formation for operations in the deep jungles of Burma miles behind Japanese lines.

One observer described Fergusson as a “monocled Old Etonian from the Black Watch with a patrician drawl”.

Sir Bernard Fergusson, GG of New Zealand. pic.twitter.com/FWg85Rp6eM

— Chris Balster (@ChrisBalster) November 20, 2016

He commanded this brigade throughout the Chindit operations of 1944 before becoming Director of Combined Operations from 1945 to 1946.

After the war, Fergusson held various positions, including command of the 1st Battalion, Black Watch.

He wrote books including The Black Watch and The Kings Enemies and Return to Burma.

During the Suez Crisis in the mid-1950s, Fergusson was put in charge of the psychological warfare component of Britain’s plan to retake the Suez Canal after Egypt’s President Gamal Nasser nationalised it.

In 1962, Fergusson was appointed Governor-General of New Zealand.

In 1972, Fergusson was granted a life peerage as Baron Ballantrae.

He died in 1980 after serving as chancellor of St Andrews University for seven years.