The voice on the end of the telephone was quiet, but lyrical.

There were no frills, but a lilting hint of the otherworldly qualities of a man who had faced many privations in his life, including tuberculosis, cancer and a variety of bronchial conditions, and wasn’t about to start complaining now he was in his 70s.

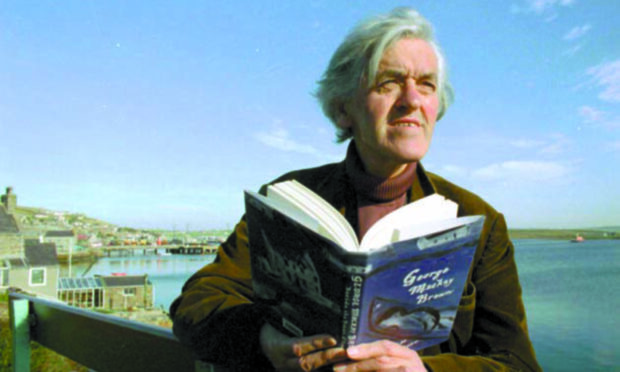

George Mackay Brown had responded to a letter I had written to him, telling him about the death of my father, David, in 1992.

The poet, who was famously reclusive and disinclined to leave his beloved Orkney, was nonetheless kind in offering his condolences and began chatting about my dad’s brother, Bill, in terms which came as close to excitement as he could muster.

The pair of them had been mature students at Newbattle College, near Dalkeith, in the early 1950s.

And, although four decades had passed, George had never forgotten meeting and savouring the company of his peers.

You can see a raincloud trailing its fringes across the horizon, between blazes of blue and gold, on many days of the year.”

George Mackay Brown on life in Orkney

“It was the happiest time of my life, and Bill was one of my friends,” he told me.

“We all wanted to be writers, and we formed a close bond.

“He went away and became a teacher, which means he helped others… I just kept writing.”

Then, just as quickly as he had been waxing lyrical, the call was finished and he was free to resume his life in the private world of his beloved Stromness.

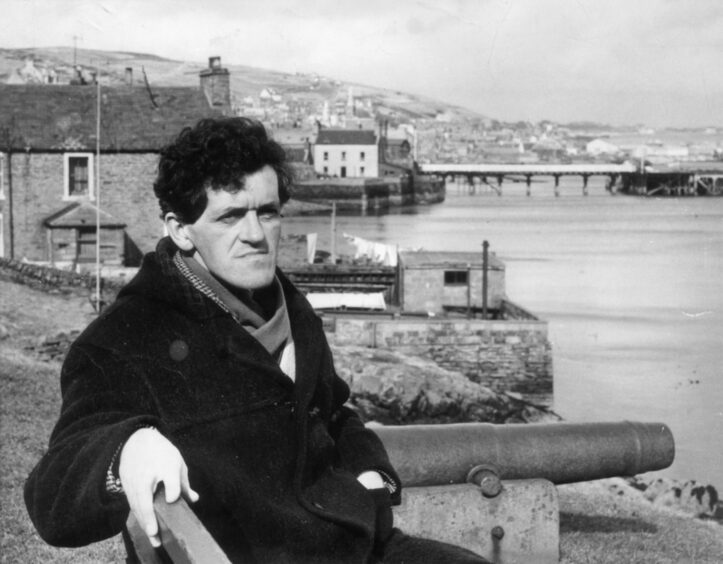

George, who was born 100 years ago, on October 17 1921, is now widely acknowledged as one of the greatest poets and authors of the 20th Century.

Ever since the publication of The Year Of The Whale in 1965, he was a prolific writer, despite being burdened with recurring health issues.

His novels Greenvoe and Magnus, which emerged in 1972 and 1973, stamped him as a unique voice, whose work was every bit as ingrained in his roots and where he grew up as Sunset Song was to Lewis Grassic Gibbon.

His short story Andrina was adapted and directed for BBC Scotland by Bill Forsyth; another individual who has never fitted easily into any mould.

He left an indelible mark on Scotland

Between 1987 and 1989, George travelled to Nairn, including a visit to Pluscarden Abbey, journeyed around Shetland – another world of wonder – and eventually took the train down to Oxford, making it the longest time he had left Orkney since his earlier studies in Edinburgh.

Shortly afterwards, he was diagnosed with bowel cancer, which required two major operations in 1990 and a lengthy stay in hospital in Aberdeen.

Yet it was typical of him that he should find inspiration in the midst of his travails and produce Foresterhill in 1992, about his recollections of the Granite City and the gratitude he felt for the medical staff who had treated him.

Brown’s poetry and prose were as sparse and lean as the man himself.

Having grown up in poverty, he was never drawn to grand ideas, but his simplicity of description, colour, shape and action merely enhanced his stature.

In life, he rarely used two words where none would suffice, but he became a familiar figure in Edinburgh’s Milne’s Bar, and shared myriad hours with such renowned figures as Hugh MacDiarmid, Edwin Muir and Norman MacCaig.

However, he was never interested in fame for fame’s sake and when his novel Beside The Ocean Of Time, which covers more than 800 years of Orkney history through the dreams of a schoolboy, won the Saltire Scottish Book of the Year Award for 1994 and was subsequently listed for the Booker prize for fiction, the news caused Brown acute anxiety.

Even now, 25 years after his death in 1996, there’s something beautiful about the manner in which George depicts life on Hoy and Rackwick, Kirkwall and Stromness and the other places where he was happiest.

As he said: “In the novel Greenvoe, I tried to give each day a distinct tone by changes in the weather.

“This is no fake contrivance, either, because visitors to the islands are astonished by the swift alternations of storm, stillness, rain, sun, sea haar; sometimes, a single day has three or four kinds of weather.

“You can see a raincloud trailing its fringes across the horizon, between blazes of blue and gold, on many days of the year.

“I don’t know how it is with other people, but with me, every day from Monday to Sunday has a distinct aura and flavour: I think memories from childhood have a lot to do with it.

“So there is the washing-day smell of Monday, the agricultural air of Wednesday (which brought the farmers and their wives to Stromness for the weekly mart), the wild sweet freedom of Friday when we burst through the school gate for the weekend, and Sunday with its stillness and unction like a white marble tombstone.”

And, of course, he was fascinated by the many ancient standing stones and settlements which proliferate on Orkney, older than the pyramids and as compelling to visitors now as they were to missionaries centuries ago.

His early days at Newbattle were one of the few periods when he was separated from Orkney, but he was caught up in the enthusiasm of a group of young, working-class students who talked, wrote and supped prodigiously.

He recalled: “It was a devoted group: Bill Drysdale from Bathgate would sit up half the night in the library writing a long play in the Shavian mode, Bob Fletcher from Airdrie wrote one or two poems, and when we sat round the table in the Justinlees bar, a mile up the road from Newbattle, it was a kind of literary revivalist meeting, tinged with politics and philosophy.

‘We decided to enter a competition’

“When, in November, The Observer announced that it was running a Christmas story competition, we all set to work and cajoled (secretary) Flora Jack into typing up our entries.

“It was a magical time.”

However, the £250 prize was eventually given not to any of the aspiring talents in Midlothian, but an almost unknown young writer, Muriel Spark, who was living in a bedsit in London and struggling to support her small son.

Less than a decade later, she created The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie and her place in the pantheon was secured forever.

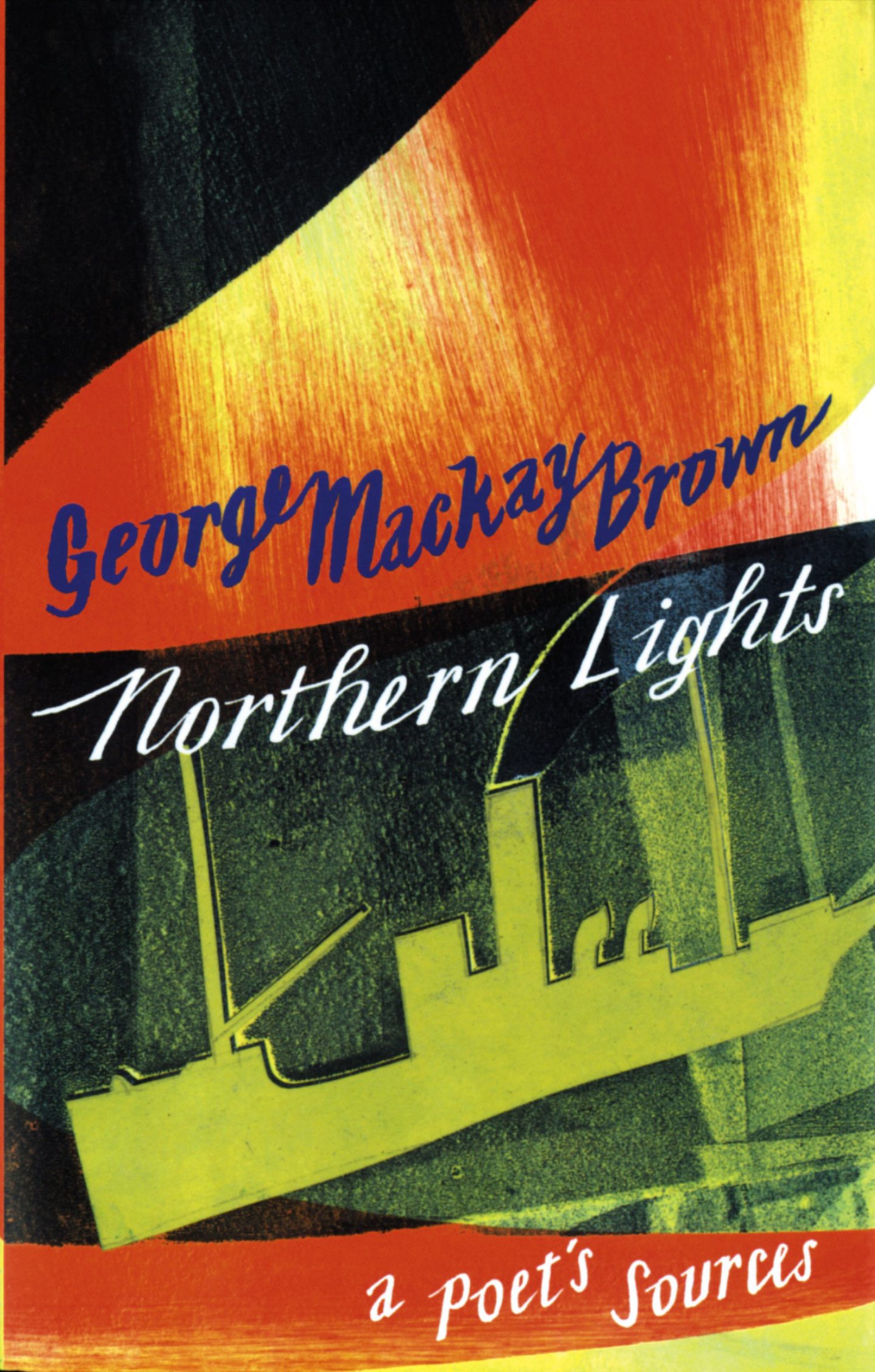

George’s work has a timeless quality that means it endures and captivates new generations.

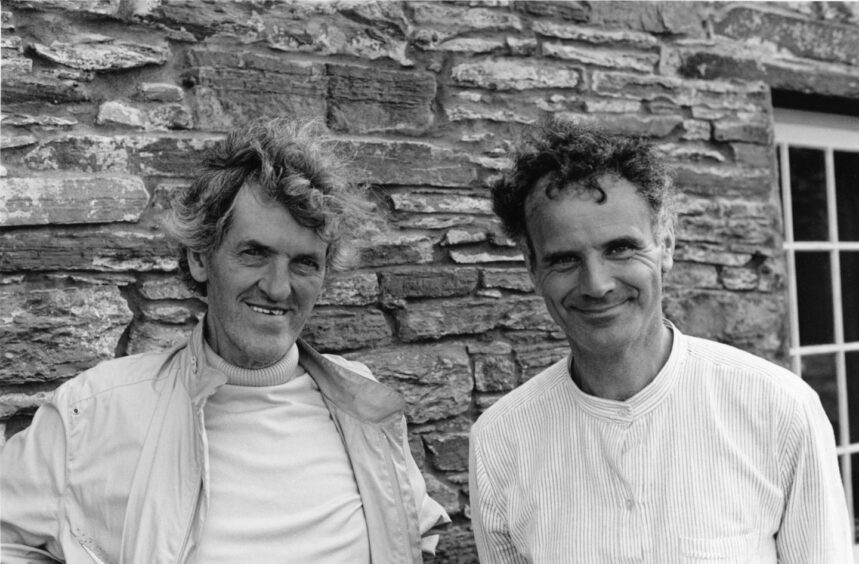

When he became friends with the composer, Peter Maxwell Davies, late in life, he also joined forces in creating musical compositions.

None of this happened by accident. But a lot of his story revolves around being an outsider.

He grew up as the youngest of six children and was often left to his own devices, which both fuelled his imagination and meant he was prone to bouts of melancholia.

It might have been genetic – his family had a history of depression and George’s uncle, Jimmy Brown, may have committed suicide: his body was found in Stromness harbour in 1935.

But it also meant he was a lone voice, a genuine one-off in his domain.

As he wrote in his autobiography: “There are mysterious marks on the stone circle of Brodgar on Orkney and on the stones of Skara Brae village from 5,000 years ago.

“We will never know what they mean. I am making marks on a piece of paper that will have no meaning 5,000 years from now. A mystery abides.

“We move from silence into silence and there is a brief stir in between, every person’s attempt to make a meaning of life and time.”

In the early spring of 1996, while I was working for Scotland on Sunday, there was an idea that we should prepare a 75th birthday appreciation of George.

Initial plans were formed, and I thought it would be best to visit him in the one place where he would be at his ease.

But then, just a few days later, came the news that he had died at Balfour Hospital in Kirkwall.

The tributes were effusive

The obituaries which appeared paid full justice to his gifts, and demonstrated how his work had resonated with readers and critics all across the world.

Reviewing his 1987 collection A Time to Keep and Other Stories in The New York Times, Sheila Gordon wrote that in his “marvellous stories,” the author “holds us in the same way that the earliest storyteller held the group around the fire in an ancient cave”.

George would have liked that.