We think of them as the ‘tough’ generation, those of the war and post-war years who learned to grit their teeth through the deprivations and ‘just get on with it’.

Perhaps the toughest of all were those who suffered from polio during the outbreaks of 1947-50, and 1954-58.

For reasons still unknown Moray and Nairn were particularly badly hit during the epidemics of the 40s and 50s with 159 cases in total, and a further two notifications between 1959 and 1963.

To this day, survivors don’t like to talk about what they endured as very young mites from a horrible disease, because they ‘just got on with it’, determined to make successes of their lives.

Poliomyelitis affects the nervous system, and can cause paralysis and weakness in the limbs of sufferers.

Devastating for children

It hit children particularly fast and hard.

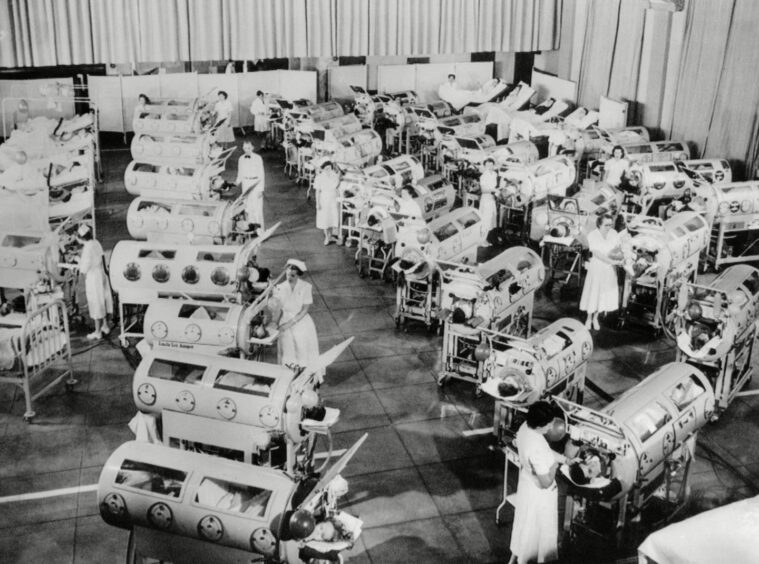

If it went to the chest, patients had to be helped to breathe with the aid of an iron lung.

If it attacked the limbs, the children were condemned to long hospital stays and intensive physiotherapy for years.

Callipers would be fitted to weakened limbs, and sometimes children would grow strong enough to leave them behind.

Sometimes not.

Worst of all was the perceived shame of the disease.

No one wanted to talk about it, least of all the survivors.

Amputation sometimes the only option

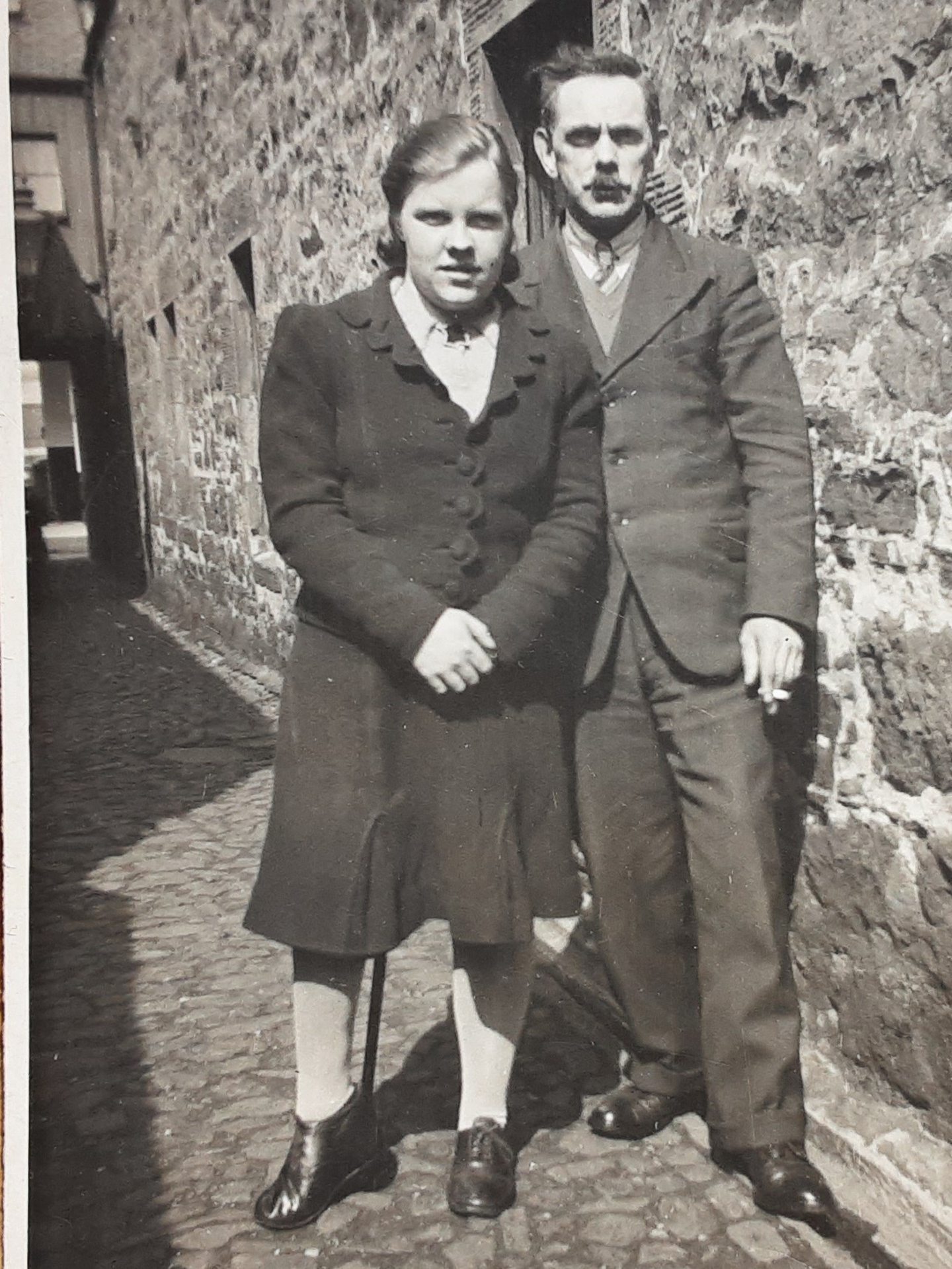

Neil Phimister’s late mother Mabel came down with polio aged eight in Elgin in 1929, and he has only discovered more about what she went through after her death.

Mabel was left with a withered leg which was so weak “she couldn’t wait to get rid of it,” Neil says.

“Once she reached the aged of 21 she chose to have the leg amputated.

“There weren’t many things she couldn’t do.

“If she decided to do something, she was very determined, and nothing stood in her way.

“She was well-known in Elgin, working as a cashier in Strachan’s butcher’s shop for years.”

Mabel was also very active in the community, learning to drive and to swim when she was 60.

She lived until almost 90, accompanied by her ‘just get on with it’ attitude, and volunteering for polio charities.

Driven by positive attitude

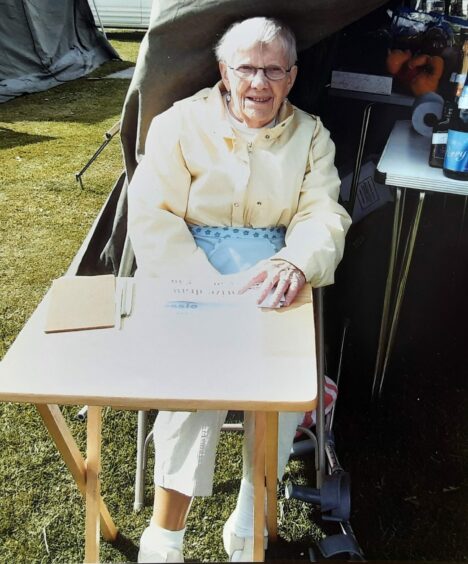

Elgin polio survivor Marlene Hay also has a ‘just get on with it’ attitude, and tends not to dwell on those days.

She contracted the disease during the 1949 epidemic when she was three.

She doesn’t remember the early years of it, but what still traumatises her is the terrible heartache of being separated from her mother and only able to see her through glass.

She was transferred to a hospital 100 miles from home for rehabilitation, and it was almost a year before she saw her family again.

Kindness of hospital staff

During this time, she formed close bonds with the staff there.

As it was post-war, there was still food rationing, and her family regularly sent apples, oranges, eggs and sweets to the hospital.

The local Girls’ Brigade made it a project to send letters and pictures.

Marlene had about a year in hospital before she could get home, aged 4.

Her relatives told her only very recently they couldn’t get over the change in her when she got out of the car, from a toddler with blonde curls to a little girl with straight hair and speaking properly.

Casting off her calliper

She had a calliper on her leg, but thanks to intensive physiotherapy and cycling about on a tricycle from five years old, she eventually didn’t need it.

“Gym and sports were hard,” Marlene said.

The disease affected her left leg and both feet, but nothing would stop her from making the most of her life.

Secondary school was hard, as Marlene ‘just wanted to be normal’, but she overcame, went on to marry, have three children and work many years as a secretary in the NHS.

She says: “It was a feared disease. People didn’t talk about it. We got on with it. I have friends who to this day don’t know I had it.”

Post-polio syndrome a harsh reality

Cruelly, the disease has decided to hit back at Marlene in her later years.

She has the little-known post-polio syndrome, with constant fatigue, aching joints, bones and breathlessness.

She’s only speaking out now to try to raise awareness of the syndrome, which affects many survivors and can kick in decades after the initial attack.

Researching the Moray outbreaks

Elgin man Donald Lunan has researched the Moray outbreaks extensively for a talk he gave to Elgin Rotary Club.

He spoke to many survivors and has built up a picture of how the dreadful disease affected its youngest victims.

Exercises, exercises

“They don’t remember the particular trauma of hospital admission; they don’t remember being in pain with their paralysis; one poor child entered hospital paralysed from the neck down; they remember exercises, exercises.

“I was struck by how warmly all spoke of their carers and nurses in their sometimes months-long stays, with one being told in later years that she apparently didn’t want to leave her ‘new family’, while others felt they came home changed, looking and speaking differently.

“Local neighbourhoods and churches and schools often kept in touch with their ‘lost child’ and would send parcels and messages, but children weren’t allowed to take their toys or dolls back home.”

Well-known Dundee man’s experience

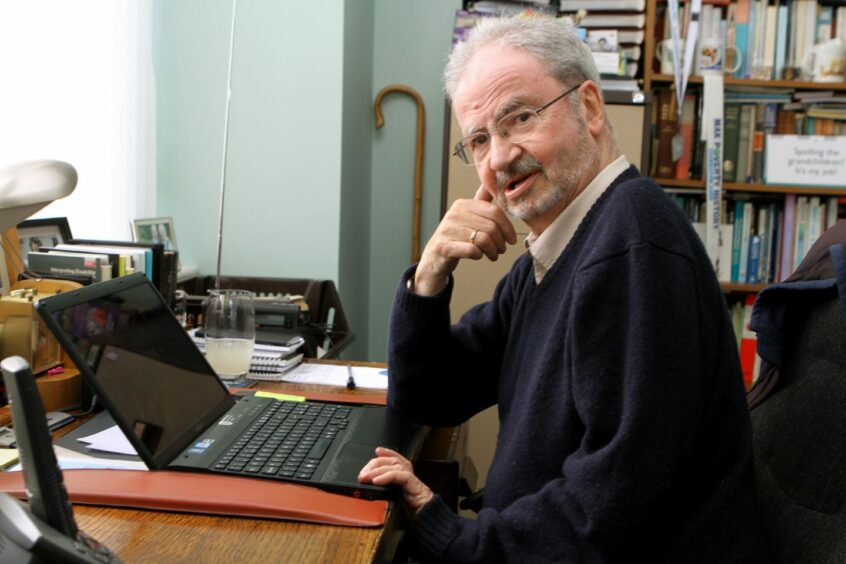

Post-polio syndrome has affected Rev Erik Cramb of Dundee, too.

Retired now, Erik was well-known as a Church of Scotland minister and industrial chaplain in Dundee.

He contracted polio as a baby in Glasgow’s Maryhill, and it attacked his arms and legs.

“I don’t remember much until I was about seven or eight years old,” he says. “After a series of operations I got the hip length calliper replaced by a below the knee calliper that hugely improved my mobility, and I was able to go home from hospital in the evenings.

“It was a huge step forward.”

More operations followed when Erik was aged 10-11, but eventually he got rid of his calliper and was able to walk unaided.

Table tennis champ

He even took up table tennis and became a first division player until he was warned that if he continued at that pace he would be back in a calliper by the time he was 40.

Initially Erik’s desire to go to university was discouraged, and he was told to get a job ‘while you can’.

But seven years later he was able to get to university where he discovered theology and went on to become a minister of the Church of Scotland.

His work took him to Edinburgh, Glasgow and Jamaica before Erik and his family moved to the manse in Clepington Road, Dundee.

From here, he was minister and chaplain to a raft of public bodies, from Tayside Region to the Forces and industries like Michelin, NCR and Ferranti.

Supportive

Erik says his childhood was blessed by supportive parents who didn’t hide him away and battled to get him into mainstream education; his teachers, and particularly his generous younger brother Michael who had to accept the role of second fiddle around Erik’s years of treatment.

“It wasn’t until the hormones kicked in and I became conscious of my body that I knew I was different,” Erik said. “But I had good pals, was a good story teller, and was lucky enough to meet my wife as a student on a summer camp in Canada.

“We recently celebrated our golden anniversary.”

Post-polio syndrome has surfaced for Erik, and he too wants to raise awareness of its devastating effects.

Lest we forget — vaccination stops polio

For Donald Lunan, the importance of polio vaccination is highlighted by his daughter Jennifer, who spent a year working as a physiotherapist in Cambodia in 2004.

“She told me there were young adult polio sufferers around.

“Thirty years before, under the horrific Khmer Rouge regime, immunisation programmes stopped, and polio quickly got a hold again, for years.”

You might like:

Thousands of children unprotected against polio, data shows

What is polio and what happened the last time there was an epidemic in the UK?