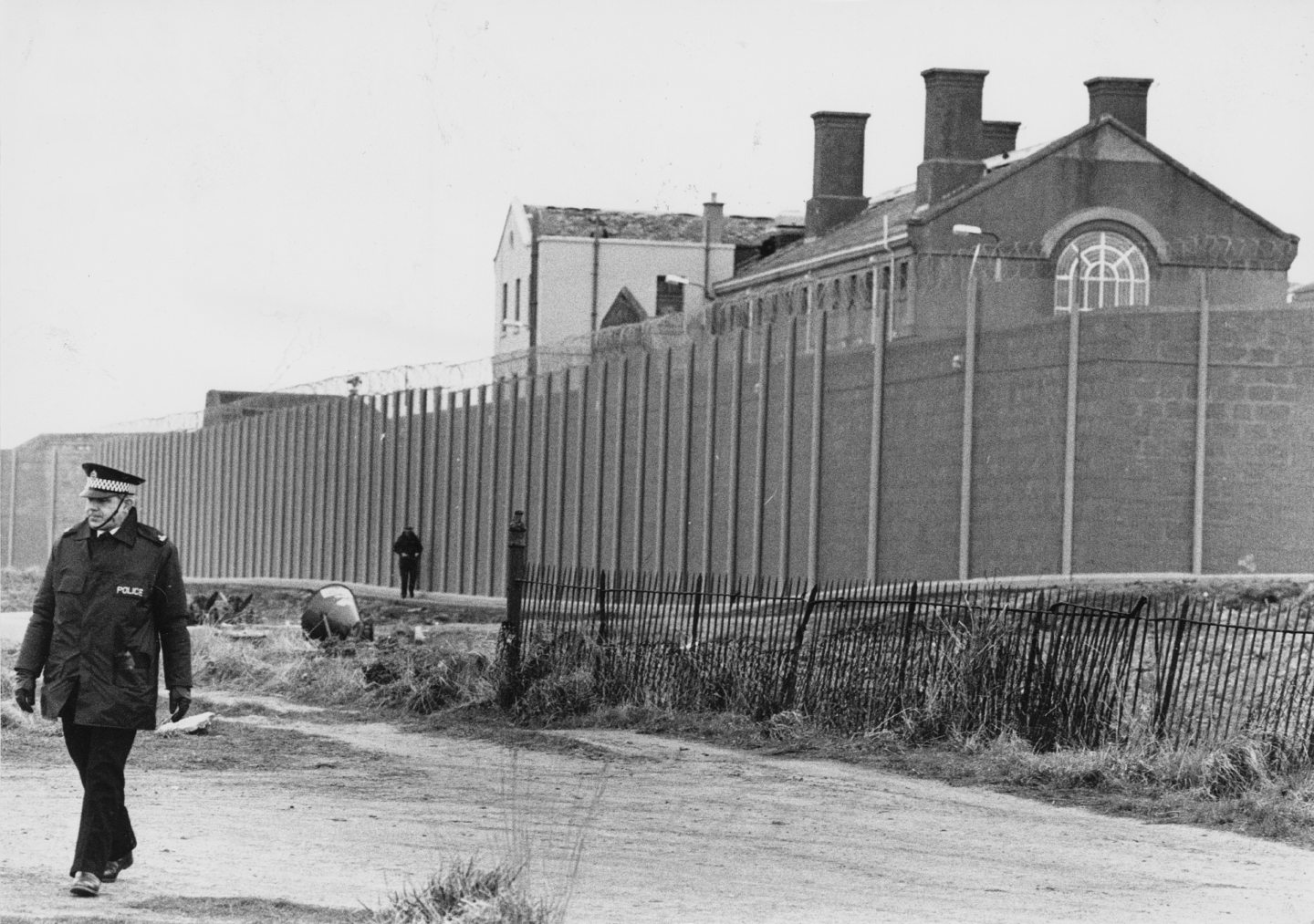

The Hate Factory was one of the nicknames attached to Peterhead Prison and that sums up the often desperate and brutal nature of the people who were incarcerated behind its imposing walls.

There was never any prospect of this place producing positive headlines.

But even so, few were prepared for what happened when a group of inmates rioted in September 1987, took control of part of the building, and held a man’s life in their hands.

In the days that followed, as September turned into October, their actions sparked a serious incident at “Scotland’s Gulag”, led to the abduction of a hostage, were the catalyst for an urgent debate at Westminster and required the intervention of the SAS.

Peterhead prison officer Jackie Stuart was already 57 by the time of the siege at the notorious jail which commanded global headlines 35 years ago.

Jackie returned to work weeks later

And yet, although he was stabbed several times during his harrowing ordeal, which dragged on for five days, he never allowed it to affect his life.

Indeed, six weeks after it happened, he had returned to work, blithely unaware of such conditions as post-traumatic stress syndrome.

And even now, at 92, the north-east father-of-six still acts as a guide for visitors at Peterhead Prison Museum.

It has changed beyond all recognition from the saturnine citadel which formerly housed thousands of Scotland’s most notorious criminals during its 125-year history.

But while there had been outbreaks of lawlessness at other Scottish jails in the months leading up to the explosion of violence at Peterhead, nothing could have prepared Mr Stuart and his fellow staff members for the riot which erupted on September 28 in D-Wing.

As he told the Press and Journal: “A colleague had placed one of the inmates on a minor report in the morning, but in the evening, when they [the prisoners] were out for leisure, the inmate tried to stab the officer who was involved.

“I went to his aid, but after wrestling him to the floor, I noticed the whole hall had become involved in the incident and events just spiralled from there.

“My attitude to life is that if something happens, it happens, and you have to make the best of the situation in which you find yourself.

“I always look on the positive side of things, and that kept me going throughout the next few days.

“But, because one of the group of inmates could best be described as erratic, there were times when I was unsure how events would unfold.

“My focus throughout it was to try and keep everybody calm and not inflame the situation.”

Story made international headlines

Mr Stuart’s sangfroid was hardly shared by his work associates after he had been taken hostage and a sense of anxiety and apprehension enveloped the prison.

After all, the ringleaders in the riot included such uncompromising characters as Sammy “The Bear” Ralston, Douglas Mathewson and Malcolm Leggat, who had previously shown they had scant regard for human life and weren’t afraid to get their hands dirty.

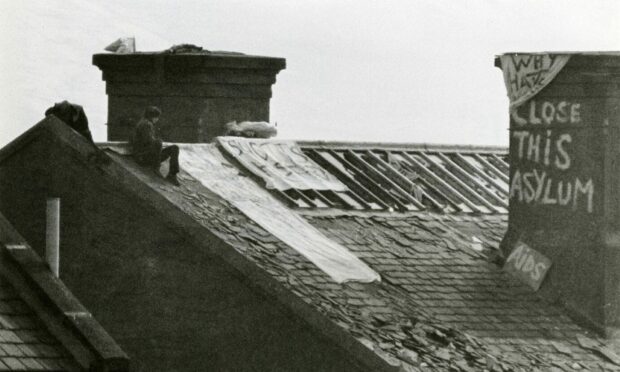

After seizing Mr Stuart, they moved to an area in the roof space of the prison and created a variety of barricades and booby traps, deploying such items as burning bedding and soiled sheets to ensure that nobody could get near them.

As news spread of the crisis, the BBC screened footage of Mr Stuart being hauled onto the rooftop, where a hooded prisoner swung a weapon at his head.

Not surprisingly, the story commanded the international spotlight and prime minister Margaret Thatcher decided the impasse could not be allowed to continue in case inmates at other jails throughout Britain leapt on the bandwagon.

It was at that point in the stand-off when the prison authorities liaised with senior politicians and the SAS’s involvement was sanctioned.

However, one officer, who requested anonymity, told the Press and Journal in 1988: “It was very controversial, and not everybody agreed with the decision.

“Sending in UK special forces to handle a domestic criminal incident was very different from the normal way that these affairs were handled.

“But, of course, it was all about saving Jackie’s life and that had to take precedence over anything else.”

Back on the roof, Mr Stuart was at the mercy of his captors for days on end.

He explained, in a down-to-earth fashion: “I was stabbed three times throughout the ordeal, twice in the arms and once in the side, but, to be honest, I didn’t really feel that much.

“They even hit me with a chair leg and put it round my throat at one point.

“Some people may think it would have been horrific. It was an experience I will certainly never forget.”

But, as his fate hung in the balance, developments were moving swiftly elsewhere.

The SAS moved in without any fuss

At the start of October, about 20 men from the SAS’s on-call anti-terrorism team were flown from RAF Lyneham in Wiltshire in a Hercules aircraft to Aberdeen, before being driven under police escort to Peterhead Prison, where they prepared for their response.

As Bryan Glennie, another prison officer on duty during the siege, recalled: “We had just taken up duty early in the morning [at 5am] and were sitting in the cell when it all kicked off.

“There were several explosions and flashes and there was smoke everywhere and, within a few minutes, the prisoners were being marched down the stairs, one by one, to the ground floor by the SAS soldiers.

“We had been sitting on the front line, but the rescue plan was unknown to us. The good news was that Jackie was safe.

“The SAS had obviously looked at plans of the prison well in advance and worked out the best way to get Jackie out.

“The whole operation was done precisely and without any fuss. I was there and I had a job working out how it all happened, as did the other members of my team.”

Mr Stuart was also in the dark, although he was grateful for the intervention which was done and dusted almost in the blink of an eye.

As he said: “This was possibly the worst part, because I had no idea they would be coming in, and when the stun grenades and tear gas were thrown in, it took me by total surprise, as it did the inmates.

“But I was then removed from the scene by an SAS officer and ran back along the roof to a rope, which then led me to a ladder, which took me to another SAS officer and to safety. It was all over very quickly.”

Even now, in his ninth decade, Mr Stuart still seems bewildered at the speed with which the siege was brought to a conclusion.

Others might be equally surprised at how swiftly he himself recovered from his brutal treatment, but he’s made of stern stuff.

Jackie got back to work afterwards

This was in the days before there was any real recognition of PTSD and its after-effects and he received little more than a physical check for cuts and bruises, prior to returning to normal prison duties in November, 1987.

His response perhaps summed up why he seemed so unperturbed. As he commented: “Well, it was part of my job, I just got on with things.”

The perpetrators of the riot were struck with lengthy extensions to their existing punishments.

But there was no admission by the government that they had called in the SAS until more than five years later in 1993.

And secrecy still surrounds aspects of the operation even though it brought matters to a peaceful conclusion.

Indeed, even the SAS’s official account concluded: “In a short time, the prison authorities came in, reclaimed the building, and took charge of the inmates, while the SAS melted into the shadows.”

Peterhead Prison closed in 2013 and was replaced by HMP Grampian.

But Mr Stuart returned to his old haunts when the museum opened in 2016 and many tourists have been impressed after chatting to him in the admissions area about his experiences.

As he remarked: “Being involved since day one of the museum project has been enjoyable and it is great to see what a huge success the whole development has been.

“Meeting such lovely people is a huge difference to my former life inside these walls. It is terrific somebody has done this at the prison, because it was lying empty for a while.”

That feeling was reciprocated by Alex Geddes, the operations manager at the popular visitor attraction.

He said: “Working with Jackie has been a great honour and his presence in the halls since we opened our doors has received plenty of terrific feedback.

“His pragmatic approach to the incident, plus his general service over the years, speaks volumes in relation to his character and, in a very positive way, he is ‘old school’ in his work ethic and his dedication to the service.”

Many others might have wanted to get away from the building and never go near the place again after suffering such an ordeal, but not this exceptional nonagenarian with a stiff upper lip and a spring in his stride.

Jackie Stuart escaped once from Peterhead.

He clearly has no wish to break out again.

Conversation