Scottish Government ministers have been accused of trying to avoid scrutiny after reports revealing falling exam passes were “snuck out” at 8pm last night.

The four papers, which provided analysis of the 2019 school test results, were made available online after “a series of freedom of information requests and appeals spanning several months” from a university lecturer.

The timing and manner of the data release has led to ministers being accused of a “snide and cynical” attempt to avoid scrutiny of its record on education.

You know what's *really* interesting? These are the documents that the government released to me 32 minutes before publishing them online. I (we) got them after a series of FOI requests and appeals spanning several months #transparency https://t.co/8VjM3HShc3 pic.twitter.com/JbNRuDJkve

— James McEnaney (@MrMcEnaney) February 20, 2020

The SNP are not the first party to face such accusations however, as Holyrood and Westminster governments have a long history of “sneaking out” uncomfortable announcements and statistics.

‘A good day to bury bad news’

Perhaps the most memorable example of a government trying to conceal an announcement was in 2001 when Labour aide Jo Moore suggested the September 11 attacks were a “good day to bury bad news”.

Ms Moore, who worked for the then transport secretary Stephen Byers, was widely condemned for showing spin at its worst when her news management memo was leaked.

She resigned the following year, but the perception that government might occasionally look to “bury” news stories during big events remained.

Take Out the Trash Day

A rather cynical tradition has developed in Westminster in recent years in which, in the final days and hours before MPs leave Parliament for recess, the government releases a deluge of reports, statistics, and statements in an apparently deliberate attempt to bury them.

In 2018, the Department for Work and Pensions faced criticism after a study – quietly published online without any ministerial announcement – found that there was “no evidence” that benefit sanctions encouraged claimants on low incomes to increase the amount they earn, despite that concept being a key component of the Universal Credit system.

In the same year the Home Office was also called out after a report was slipped out which found the government’s border ‘exit checks’ introduced to keep track of people moving to the UK have completely failed. The study, by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration found that there were hundreds of thousands of people whose right to remain in the UK had expired but for whom the government had absolutely no record of having left.

Under Boris Johnson, the practice of publishing reports “on the last day of term” has continued. Just before the Christmas break it was revealed that Mark Field, who was suspended as a Foreign Office minister after he was filmed grabbing a Greenpeace activist by the neck and forcing her out of an event, would face no punishment.

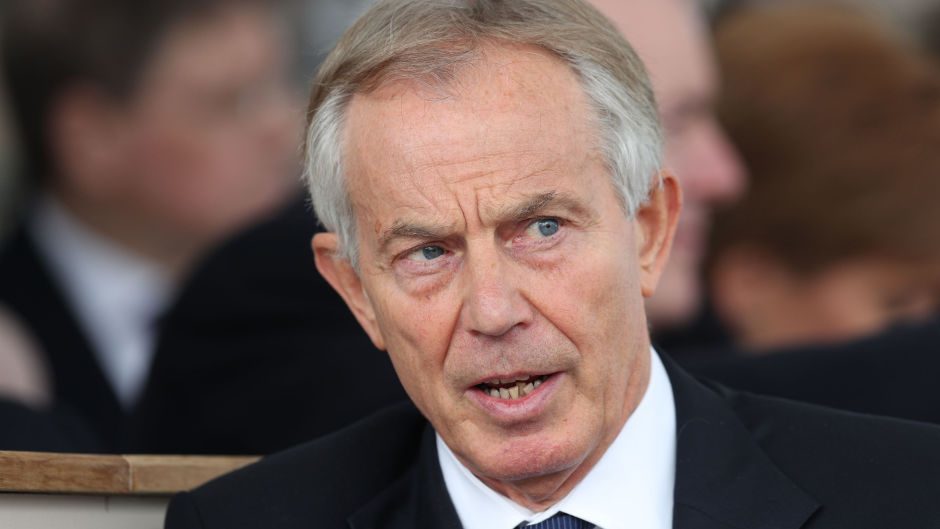

On the same day it was also revealed that the number of Special Advisers, political appointees funded by the taxpayer, had broken through the 100 barrier to hit a record high. There are now 108 ‘Spads’ across government – up from 99 in 2018, 88 in 2017 and 89 in 2016, a total that dwarfs even the ‘spin’ era of Tony Blair.

Is Holyrood just as bad?

The debacle over the school test results is the second time this month the SNP have faced accusations of trying to bury bad news.

There was a row only three weeks ago after quarterly GDP figures, which revealed £5billion had been wiped off the total value of the economy, were not announced by the Scottish government in its economic press release and were not available on its usual statistical website.

Economist John McLaren, who had to contact the Scottish government to access the GDP figures, told the Times that the move was “worrying”.

“A £5bn — almost 3% — downwards revision in Scottish GDP has important implications for judging Scotland’s economic and fiscal standing, especially in terms of independence or full fiscal autonomy”, he said.

Why do governments do this?

A difficult one to answer. With the advent of social media and the blogsphere there’s never been a more difficult time for governments to try and conceal or obfuscate. An army of activists, researches and academics work alongside journalists to peel through reports and statistics in order to shine a light on what those in power are doing.

But, as the examples above show however, the practice of downplaying or minimising announcements prevails and will more than likely continue.