How would you feel about being branded on the cheek for flouting pandemic rules?

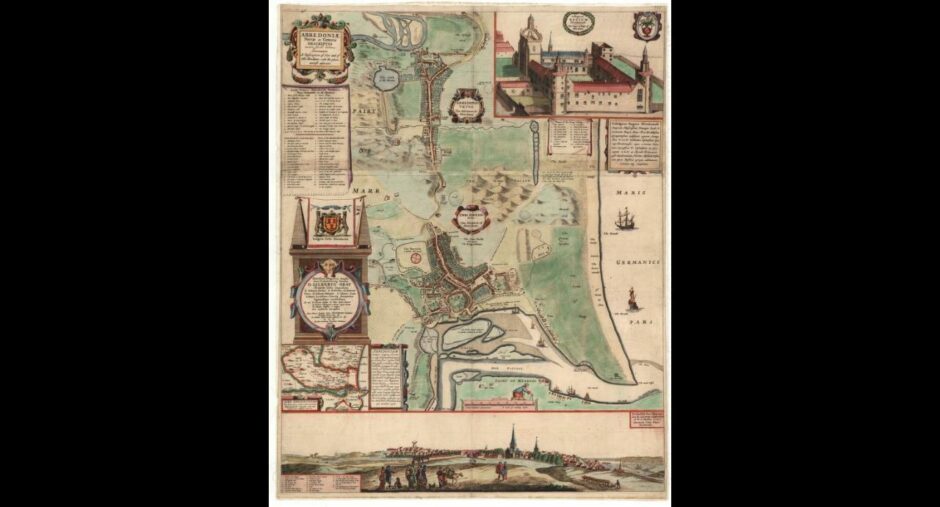

Or being sent to a camp on the outskirts of Aberdeen for 40 days to keep you away from healthy residents.

It may sound harsh but these were just some of the measures brought in to help stop the plague tearing through the streets of the north-east port in the 16th Century.

Recent lockdown rules brought in to prevent the spread of coronavirus may have been described by many as draconian.

But looking back through history it’s clear that punishments for breaking plague legislation were more extreme – with residents even threatened with execution.

Aberdeen’s law-abiding residents helped prevent the spread

Historian Dr Karen Jillings, who has written a book on the impact of the plague on Aberdeen, highlights how the measures used to contain historic pandemics were strikingly similar to those used today.

“Plague epidemics fell into a pattern by the 16th Century where most major burghs in Scotland were hit at least once every couple of decades,” she said.

“Epidemics became a regular, if unpredictable, and very disruptive feature of life.”

But Dr Jillings says Aberdeen presents a “fascinating” case study of historical epidemics because of its remarkable avoidance of the plague.

And she puts this down to the efficient response of the authorities combined with the actions of law-abiding citizens playing a “significant” factor in keeping the disease at bay.

How did Aberdeen tackle the plague?

Four measures were brought in to help prevent the spread of the plague similar to those used now in the fight against Covid-19 – prevention, detection, isolation and disinfection.

It was important for authorities to try to prevent the disease coming into the town by monitoring the arrival of people and goods and demanding proof they were plague free.

Officials believed the disease was spread in two ways, airborne vapours and contact with sources of infection.

Dr Jillings says the council ordered water supplies to be cleaned up. Butchering and tanning were banned along with the movement of cats, dogs and pigs.

Families were confined to their homes

Detection was also important and people deemed an infection threat could be expelled from the burgh.

As soon as cases were suspected in a house the whole family were confined to the home for several weeks under isolation and with armed guard. Their food and drinks were delivered through a window.

If they stayed alive they were usually released from their confinement and deemed plague-free.

But others were not so fortunate. They were sent to be quarantined in temporary plague camps set up a safe distance away on the boundaries of the town.

Houses could be destroyed when fumigated

And the conditions were not ideal.

“Conditions in these camps were rudimentary: wooden huts with straw for bedding, bread and ale to eat, and with no medical care to speak of,” Dr Jillings said.

“The word quarantine refers to the forty-day period that people typically spent there though, in practice, this varied from a few weeks to several months.

“Those who were considered to have recovered could return to the burgh with the further precaution of carrying a white stick or having a square of white cloth pinned to their chest so that healthy people were able to avoid them.”

She said infected people faced having their homes and belongings disinfected. Houses were fumigated with the burning of rosemary.

Although, most of the homes were wooden – and in 1608 one house in Belhelvie caught fire when it was being cleansed.

How were law-breakers dealt with?

Dr Jillings says compliance with plague legislation was a legal requirement.

Fines were imposed on people breaking rules, such as letting visitors climb over their back walls rather than coming into Aberdeen through official entrances.

The money was often used to pay for the upkeep of the poor, or for residents kept in quarantine.

“More severe punishments were threatened for breaking plague legislation, including branding on the cheek which, aside from being extremely painful, left permanent evidence of the misdemeanour,” Dr Jillings explained.

“Execution was the most extreme punishment that was threatened, and gibbets (gallows-style structures) were erected beside the quarantine camp as a deterrent.

“However, there is no evidence that either these or a nearby scaffold and jougs (an iron collar on a chain) were ever put to use.”

‘It was harder to get away with flouting the rules’

There’s a famous case of a man in Edinburgh sentenced to be hanged at his front door for concealing his wife’s infection.

But he was lucky that his rope broke and the council, believing this to be a sign his life should be spared, changed his punishment to a fine.

“There were certainly occasions in Aberdeen when individuals were punished for breaking plague measures,” she added.

“Having said that, while such instances were recorded, it is likely that the vast majority of people were fundamentally law-abiding and did comply with legislation in the interests both of public health and of self-preservation.

“There was more of a sense of being accountable to neighbours and fellow inhabitants. Simply put, it was harder to get away with flouting the rules!”

How similar were the measures to the ones used during the Covid pandemic?

Dr Jillings stresses that history teaches us many lessons about how we should respond as a society to pandemic outbreaks.

And many of the measures used in the fight against the plague were very similar to the tactics used today.

Today, proof of vaccination or a negative test is required to travel and in premodern times a certificate of good health was needed.

Social distancing was used in towns to help prevent the spread.

Plague doctors also wore a beak-like mask and long tunics to cover as much of the body as possible to protect themselves.

“Physicians advised people to cover their noses and mouths with handkerchiefs soaked in vinegar or rosewater,” she added.

“The wearing of masks is therefore certainly not new.”

The residents accused of deliberately spreading the plague

City records reveal that there were accusations of residents deliberately spreading the disease.

In 1547 a baker from Aberdeen was accused of travelling to Inverbervie to infect residents.

Then in 1647 a woman was said to have brought the plague from Brechin to the south-west of the burgh, which was then spread into Aberdeen by a schoolchild.

In many towns throughout Europe some residents, such as cleansers and gravediggers, were in high demand during epidemics. They could be paid high wages and were also accused of plague-spreading to profit from the disease.

How many people died of the plague in Aberdeen?

Dr Jillings says it’s difficult to say how many people died due to a lack of mortality records.

But we do have some records of deaths for Aberdeen’s third and final epidemic in the 1640s.

Around 8,300 people lived in Aberdeen at that time with an estimated 1,600 people dying of the plague in the city along with a further 140 in Futty (now Footdee) and Torry.

Most victims were buried in a mass grave uncovered during construction work in the late 19th Century to the east of York Street near the harbour.

Seventy-one victims were buried in St Nicholas kirkyard on Union Street.

And two gravestones still exist in Stonehaven on the corner of Victoria Street.

One of these belongs to a seaman who died in 1608 and two brothers aged nine and 12 were also buried after being killed by the plague on June 12, 1648.

There’s lessons to be learned from history

Dr Jillings, who studied history at Aberdeen University, researched the plague for her PhD and now teaches medieval and modern history at Massey University in New Zealand.

She said: “History teaches us so many lessons about how we should respond as a society to outbreaks: that decisive, transparent government action is vital, that scapegoating is harmful and wrong, and that complacency must be avoided.

“Whether we learn these lessons is down to us.”

If you’re interested in finding out more about the plague, Dr Jillings has written a book called An Urban History of the Plague, available at most book stores.

More like this:

Aberdeen’s 1964 typhoid outbreak: The festival that was designed to change the city’s fortunes