The coronavirus outbreak is not the first time the north-east has endured a health crisis.

In 1964, Aberdeen was locked down when a tin of corned beef led to hundreds developing the deadly typhoid fever.

As more people in the north retire into self-isolation amid the coronavirus pandemic, the comparisons between the drama unfolding today and scenes witnessed in Aberdeen in the summer of 1964 grow stronger by the day.

In mid-May of that year, a single 13-year-old tin of infected corned beef led to more than 500 people becoming hospital-bound with typhoid fever and sadly to the deaths of three people.

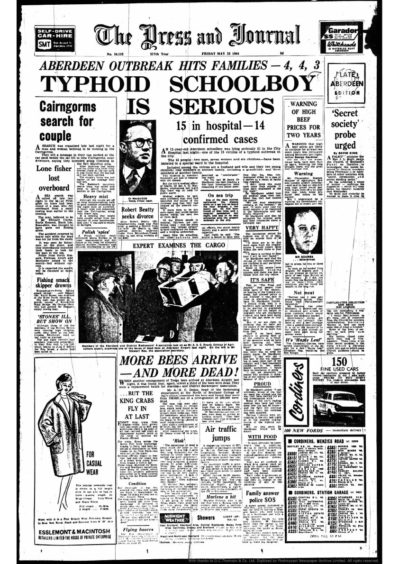

The first patient was admitted to the City Hospital, in Urquhart Road, on Saturday, May 16, and their plight first reported in The Press And Journal the following Friday.

“Aberdeen outbreak hits families – typhoid schoolboy is serious,” our headline read.

Having been exposed to contaminated food, 15 people – two men, seven women and six children – were in hospital by that time.

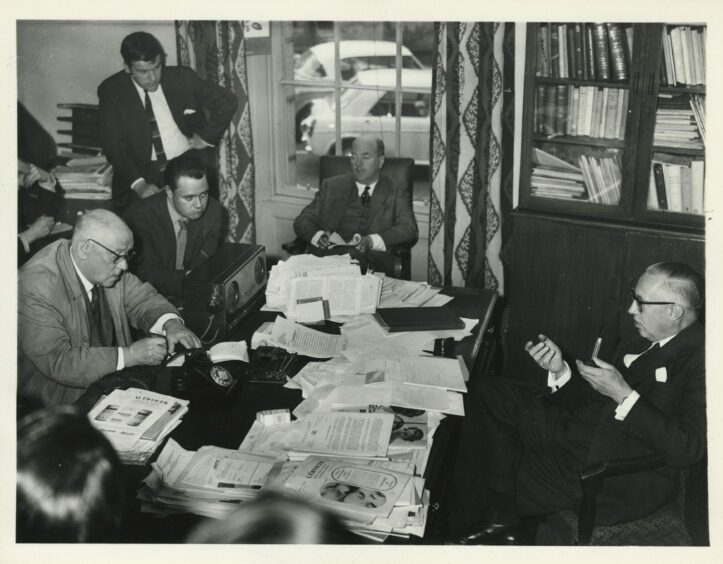

The city’s medical officer of health, Ian MacQueen, headed up a five-man investigation team to look into the outbreak.

As we now see Boris Johnson and Nicola Sturgeon leading daily press conferences, Dr MacQueen did the same.

During the first of these, he immediately addressed concerns raised by The P&J about the safety of residents – and the outlook for one of Aberdeen’s main trades.

It was reported people from across the country had inundated police with calls asking if it was still safe to travel to the Granite City, which was and remains a popular tourist destination.

Dr MacQueen confidently played down the concerns, telling reporters: “I can only put it this way. If this was happening in some other part of the country and I had reasonable confidence in the public health authorities, I would have no hesitation in going.”

By the end of May, however, 238 people were in hospital and by the beginning of August, a further 302 had been admitted.

Nearly 400 gave a history of eating food purchased from a William Low supermarket in Union Street.

The Argentinian strain of typhoid-causing bacteria was traced to a single tin of Fray Bentos corned beef, having been spread when the same knife was used to cut other meat.

But Dr MacQueen refused – despite “wild rumours sweeping Aberdeen” – to reveal where the offending food had been bought until after the worst of the outbreak had passed.

He told The P&J, on May 26, that it was “not going to do anybody any good to divulge the source”, as health authorities launched a campaign calling on former nurses to take up work again and City Hospital stopped admitting patients with other ailments.

By then, city restaurants were already feeling the pinch, hotels complained of cancelled holiday bookings and the outbreak had caused the first of many businesses to shut up shop.

Soon, responsibility was placed – much as it has been today – on the public to play their part.

Our front page on May 28 read: “Typhoid wave warning: Personal hygiene must get better,” as Dr MacQueen warned of the danger of a resurgence in the spread of the disease from secondary sources if people did not wash their hands.

The viral and bacterial nature of coronavirus and typhoid may not be the same; but as we see posters everywhere with the latest precautionary advice, the message is similar.

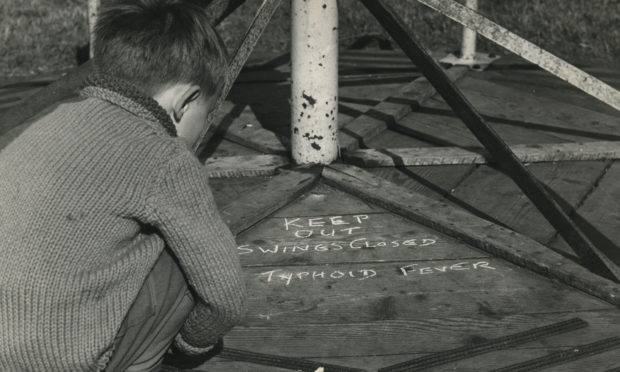

As schools remain closed – and will remain so, perhaps until after the summer – Aberdeen’s youngsters, then, too, were told to stay at home.

A fortnight after the nature and scale of the outbreak became clear, the order was given for all city schools to close.

The first death of the outbreak prompted the move, and also the turning over of Tor-Na-Dee Hospital in Milltimber, Woodside Hospital and the city’s children’s hospital to make room for more typhoid patients.

Aberdonians were ordered to cancel holidays outside of the city, while attention at Westminster cast the crisis into the national and international limelight.

The Times and The New York Times picked up on Dr MacQueen’s appeal for people “not to enter or leave Aberdeen without good reason”.

It was not until June 6 our headline read: “At last – hopeful news” as the number of new cases began to dwindle.

Despite having put the city in lockdown, Dr MacQueen took to The P&J’s front page again on June 8 to declare Aberdeen “must not be regarded as a leper colony”.

As the outbreak slowed, Aberdeen was treated to a visit by the Queen, on June 27, in an effort to show the city was once again safe to visit.

Many thousands of pounds would thereafter be spent rebuilding the reputation of Aberdeen as a tourist attraction once more.

Aberdeen Lord Provost Barney Crocket on the city’s last health crisis

In February, Aberdeen’s Lord Provost Barney Crockett – a boy at the time of ’64 typhoid outbreak – wrote to his counterpart Zhou Xianwang in Wuhan, the Chinese epicentre of the pandemic, to reassure the mayor that a city can recover from such a health scare.

The keen local historian has shared his recollections with The P&J as we look at the last time the city faced such a grave challenge.

I was 11 or 12 in 1964 and a pupil at Victoria Road School in Torry.

As a schoolboy it was an exciting time because the schools were closed.

For the first time I can remember we had daytime TV and there was educational programming put on especially to keep the kids in the house.

Unfortunately, I have to say we didn’t stay in, and instead played football, all day, every day.

I remember Dr MacQueen. His edict was pretty much law and he ruled the city with near dictatorial control.

I remember his daily press conferences.

Just right now, it feels as though there has been a lack of clarity over coronavirus and advice from the authorities is more contested now than it was then.

I think people were much more trusting then than they are now. If something was in the newspaper we all obeyed.

In the current climate we must make sure we refute rumour and the false information that can be spread so much more easily than ever before.

Back then there was no panic buying – particularly not of corned beef.

We avoided certain shops, which eventually went out of business and the economic impact – much like we are finding with coronavirus – was big.

Aberdeen was seen as a besieged city, when before that we had been a holiday destination.

We were all very proud of the response to the epidemic and that there were so few deaths.

People took a lot of civic pride in it all, though typhoid left a lasting impression on us.

We are already seeing impressive responses to coronavirus, with people helping others in their communities.

Aberdeen typhoid outbreak timeline

- May 6, 1964: The first contaminated portion of corned beef is sliced up and sold by supermarket William Low.

- May 8: Bacteria left on the slicing machine used to cut the corned beef spreads to other meats.

- May 12: The first patient falls ill.

- May 16: The patient is admitted to City Hospital and blood tests are taken.

- May 20: Lab tests show the patient has typhoid.

- May 22: Suspicions arise surrounding corned beef, with three-quarters of the 41 patients telling investigators they had eaten it.

- May 23: The William Low store is deep-cleaned.

- May 25: As the number of cases rises to 75, businesses begin to close and hoteliers report cancelled bookings.

- May 25: Doctors appeal for “fever-trained” nurses to volunteer at City Hospital.

- May 26: The Ministry of Health identifies a 7lb tin of Argentinian corned beef as the source of infection.

- May 29: City schools are closed as the first patient dies from the illness.

- June 1: More events are cancelled, with more than 200 patients now in hospital.

- June 5: City dance halls re-open.

- June 6: The rate of new cases begins to slow.

- June 12: Business leaders band together to demand compensation for losses from the government.

- June 16: Pupils head back to class as the schools re-open.

- June 17: The “all clear” is given.

- June 19: Serenaded by pipers, the first patient leaves hospital.

- June 28: 40,000 people line the streets to welcome the Queen, who signals to the outside world that Aberdeen is “back to normal”.