There’s still a long way to go to find a cure for diabetes but there have been many advances in science over the years.

And the most important milestone so far has certainly been the discovery of insulin – one of the greatest medical achievements of the 20th century.

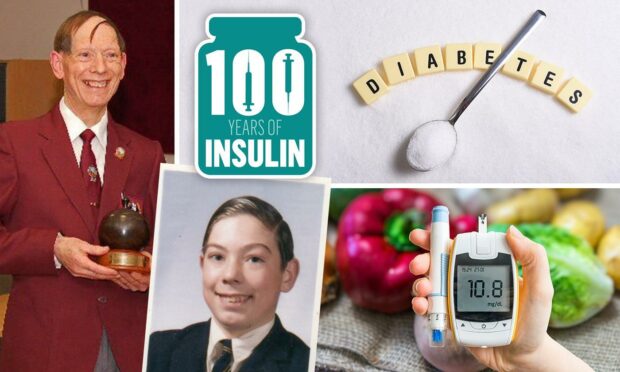

The 23rd of January 2022 marks the centenary of the first time a patient was successfully injected with the hormone which has since saved millions of lives.

In our new five-part series celebrating the 100th anniversary we’ve spoken to experts in the field of diabetes, the patients who’ve lived through many changes and the scientists involved in researching a cure for the disease.

The series starts with the remarkable story of John Macleod, a pioneering Aberdeen-educated scientist whose work played a key role in the discovery of insulin.

And it ends with the story of the next generation of scientists working at the same university to find a future cure for patients.

Who was this great Aberdeen scientist?

But the men’s journey was not an easy path to travel and the important medical milestone soon became mired in controversy.

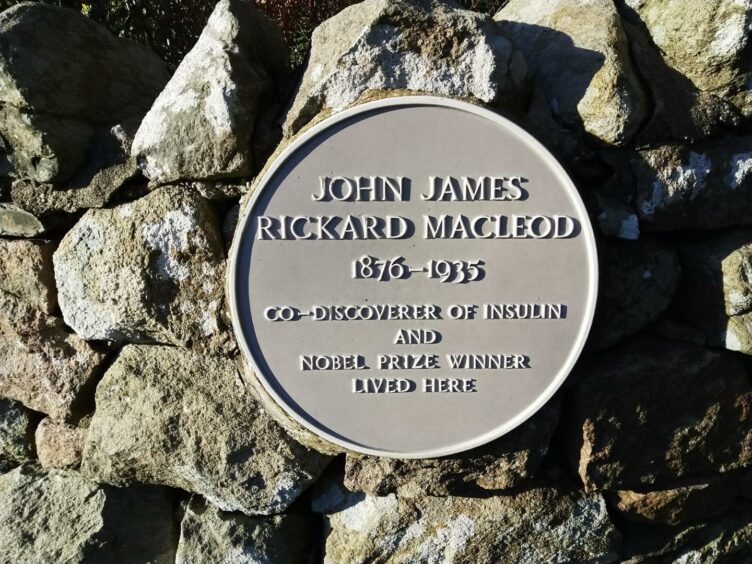

John Macleod, who was born near Dunkeld in 1876, grew up and was educated at Aberdeen Grammar School after moving to the city at the age of seven with his family.

He was a hard-working student winning many prizes while studying medicine at Marischal College.

After graduating, he won a travelling scholarship allowing him to undertake a year of research in Leipzig, in Germany, later returning to the UK where he worked at the London Hospital Medical College.

The map below shows points of interest relating to the life of Macleod and Aberdeen doctor Robin Lawrence who became one of the first patients in the UK to receive insulin

He then moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where his interest in carbohydrate metabolism led to his first paper on experimental diabetes being published in 1905.

Patients diagnosed with diabetes faced a death sentence

There were no useful medicines available to treat diabetes in those days and patients effectively faced an early death sentence when diagnosed with the condition.

“For those with what we now know as type 1 diabetes, you could survive by going on a near-starvation diet, effectively shrinking your body to a size that matched the tiny amount of insulin you could still produce,” explains retired diabetes specialist Dr Ken McHardy.

“So only those who were tough enough to handle the fatigue, wasting and hunger were the ones who could survive for any length of time.”

How was insulin discovered?

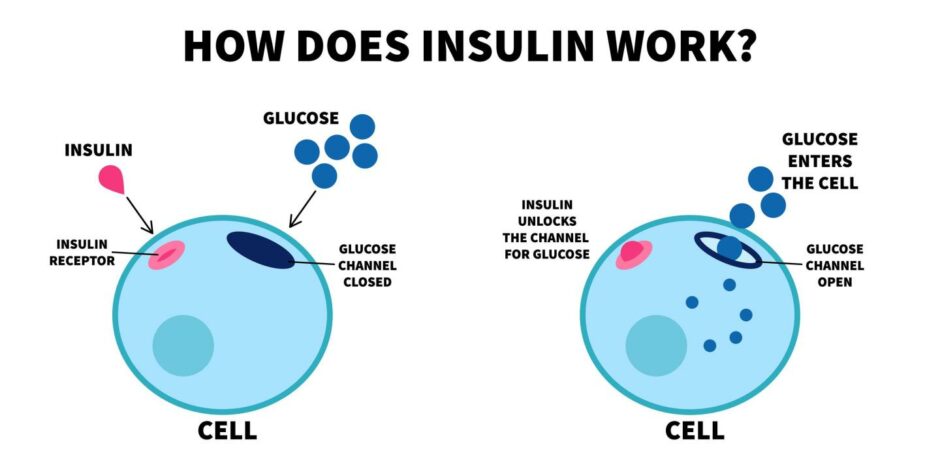

By the end of the 19th Century, it appeared likely that a defect in the pancreas might be linked to diabetes.

Researchers had tried isolating a pancreatic extract to lower blood sugar but there were doubts that this would ever prove useful.

Then a war decorated doctor living in London, Ontario, came up with an idea after studying journals while preparing for a lecture in late 1920.

“Macleod, who was always well known for supporting and encouraging young scientists – quite remarkable really when you’ve got a non-academic turning up with this idea – said if he wanted to he could come back the following year and he would give him some lab space,” Ken said.

“Banting closed up his practice and arrived in Toronto the following May to start these experiments.”

Banting had meetings with Macleod to discuss plans for the research and was assigned the help of Charles Best, a summer student, to carry out experiments.

By the end of July, they had managed to prepare an extract that could lower blood glucose.

But these extracts were impure and variable in effect and toxicity.

Biochemist James Collip then joined the team in December and started to work on concentrated alcohol extracts to clean up impurities as suggested by Macleod.

On 23rd January 1922, this extract was injected into the body of 14-year-old Leonard Thompson, who was so ill he was drifting in and out of a diabetic coma.

He was close to death but the insulin restored his blood glucose levels back to normal and his symptoms began to disappear.

The group then showed the world they could make a pancreatic extract, soon known as insulin, that could be used to treat human diabetes.

“It marks a miraculous discovery,” Ken said.

“What the Toronto group gave to the world was a well-produced preparation which could be injected day upon day to people with diabetes and therefore save their lives.”

What happened after insulin was discovered?

Banting and Macleod were awarded a share of the 1923 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for their achievements in the discovery of insulin.

But the relationship between the pair had become fractious and Banting, outraged, initially refused to accept the award.

He believed that Macleod had not made an important contribution to the work and announced that he was going to share his prize money with Best. Macleod gave half the money he was awarded to Collip.

Insulin first became officially available in the UK in 1923, and another doctor, who also hailed from Aberdeen and attended the same city school and university, was one of the first patients in the UK to receive the life-saving treatment.

Robin Lawrence later dedicated his life to helping other patients, setting up the Diabetic Association with novelist HG Wells in 1934 to ensure everyone in the UK had access to it.

It later became known as the charity Diabetes UK which continues to support scientists researching new life-changing discoveries.

John Macleod has ‘been forgotten about at home and abroad’

The charity has since funded the first-ever insulin pen and pump and has also helped prevent sight loss in many patients through the national rollout of eye screening programmes.

Macleod himself continued to carry out his own insulin research and eventually returned to Scotland in 1928 to become Regius Professor of Physiology at Aberdeen University.

Ken, who describes the physiologist as an “international hero”, says he was troubled with rheumatoid disease in his later years and ill health curtailed his ability to work and travel.

“Following his return, it seems he seldom talked about his time in Toronto and sadly he was soon forgotten about both at home and abroad,” he said.

Macleod died in 1935 and is buried in Aberdeen.

For more information on John Macloed and Robin Lawrence visit the Aberdeen City Council online exhibition which explores the lives of the pioneering men.