Mitch Mearns’ overriding feeling when he had a stroke at the age of 30 was: ‘Well, this is weird’.

After all, Mitch was a regular guy. He exercised, had a steady job in technical assistance and a two-bed house in Aberdeen.

This kind of thing wasn’t supposed to happen to people like him.

But then things got weirder.

Locked down in hospitals because of the Covid-19 pandemic, Mitch found himself isolated on stroke wards with only much older people for company.

At one point, he was stuck in a hospital just a few hundred metres from his parents’ house but with no prospect of going home.

His old life was blocked off.

Meanwhile his new life was one of strange bedfellows twice his age, and where refuge was repeat viewings of the movie Meet the Parents and TV show Only Fools and Horses.

It added up to a unique and extended out-of-body experience.

“There was a sense of disbelief,” says Mitch, who has since made a full recovery.

“It was an odd sense that this kind of thing never happens to me. So this must not be me.”

What does it feel like to have a stroke at 30?

The ordeal began in mid-2020 with a stiff shoulder that Mitch put down to sitting at his home office desk too long.

Then, one day, as he walked down the stairs one evening while visiting at his parents’ house, he felt a cold splash on his neck.

He describes it as like the first drop of rain ahead of a downpour. But instead of falling on your skin, it lands inside your head.

He sat on the sofa and tried to call his grandmother, whom he was supposed to visit that night.

But the fingers on his right hand wouldn’t do what he wanted them to do.

As the letters he typed on the screen became increasingly garbled, he had the first inclination he was maybe having a stroke.

The next thing he remembers is his mum telling him she is taking him to hospital.

By this time, he was unable to speak — the words formed clearly in is head but came out as just a mumble when he tried to articulate them.

At the hospital, medical staff confirm his and his parents’ fears: It was a stroke.

The journal that turned into a book

From there, Mitch went on a long and winding journey through an Aberdeen health care system dealing with a global pandemic.

It was the first lockdown, and access to hospitals for relatives of patients was severely restricted.

So Mitch had to cope with his condition and his recovery largely on his own.

To help ease his mind, and to catalogue everything that happened to him, Mitch kept a journal.

That formed the basis of a book, A Cage Within A Cage, published earlier this year and in which Mitch — writing under his full name Michael — recounts the story of his stroke.

It is an invaluable insight into not only what it feels like to have a stroke, but the small details of what it is like to recover from one.

“Initially, when I wrote it, I didn’t think of doing anything much more than just writing it down to remember it,” Mitch tells The Press and Journal. “I wanted to write about it while I still remember that quite vivid detail.”

How Del Boy and Rodney helped with stroke recovery

The book is full of strange, and often funny, moments. Mitch’s grim determination to hold onto his coat while being admitted to hospital, for example.

Or the time he watched Meet the Parents four times in a row as a mental escape.

“I was starting to mime the words as characters were saying them,” Mitch recalls with a laugh of his repeat viewing of the Ben Stiller and Robert De Niro comedy.

But there was also a serious side to his viewing habits. Watching the comedy allowed him to work on controlling his laughter, something that had been affected by the stroke.

“I couldn’t control how much I was laughing, so that was partly why I chose that one,” he explains. “Also, there was a limited option in the hospital so I didn’t have much choice.”

Meanwhile, watching classic British sitcoms such as Blackadder and Only Fools and Horses reminded Mitch of watching them at home on the sofa with his dad.

In the isolation of the hospital ward, they were a connection to his family.

“There are programmes that even now we can always stick on in the background, and the two of us just enjoy watching.”

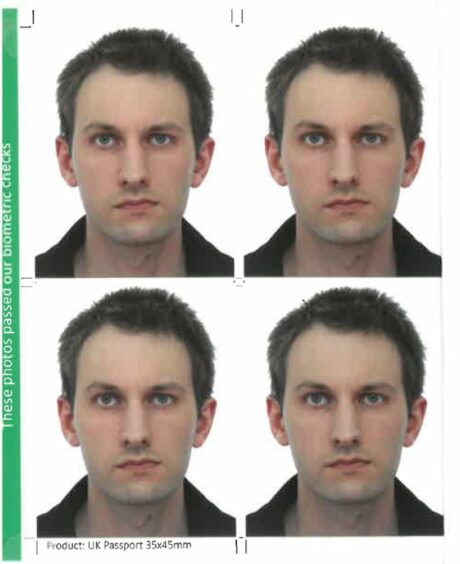

The time Mitch tried to get passport photos

One detail that stands out is Mitch’s reluctance to look in a mirror while in hospital.

He felt sure that his face showed the effects of his stroke, which made him self conscious.

So when he was discharged and had to get some passport photos taken, he couldn’t quite get the pictures he wanted.

“The amount of times that I redid those things because I just felt the right side of my face looked slightly off,” he says. “I kept redoing it again and again and again until eventually I had something I could settle with.

“I still think it looks slightly off. I’m not making any kind of facial reaction or anything and one side still looks slightly different from the other.

“It’s just something that basically I’ve got no choice but to live with.”

Did Mitch try to make a break for it in hospital?

One positive aspect about having a stroke at such a young age (the median age in the UK is 77, according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) was that Mitch recovered much faster than those around him.

This made him a star pupil with his physiotherapists, and made Mitch realise that he would eventually recover.

That was especially important during his time in the stroke recovery ward at Woodend Hospital where he was confined either to a bed or a wheelchair.

The unit sits across a field from Mitch’s parents’ home, and he felt frustration at being so close to normal life but at the same time a word away.

In the book, he writes about the prospect of escaping, of racing his wheelchair across the field to his parents.

Is it something he would have done?

“Nothing would have come of it and I could have ended up hurting myself,” he says now.

“Also, it rained a lot. I’m not sure a wheelchair would have gone that smoothly over a muddy field.”

A Cage Within a Cage by Michael Mearns is available from Olympia Publishers for £6.99.