November 5 is traditionally a night of fun and fireworks, but in wartime a terrifying bonfire night blitz brought death and destruction to the streets of Fraserburgh.

While the bombing of Aberdeen is well-documented during the Second World War, the coastal towns of Fraserburgh and Peterhead also suffered dreadfully.

While it didn’t have the allure of the shipyards of Aberdeen and Clydebank, Fraserburgh was still a strategic target for Nazi bombers.

And on Guy Fawkes night in 1940, at least 31 people were killed in the town when the glare of a fire attracted the gaze of enemy eyes.

Why Fraserburgh became Nazi target

Unluckily for residents, Fraserburgh was the first part of British mainland the Luftwaffe flew over from their base at Trondheim in Norway, making it an easy target.

Often bombers would discard their loads in Fraserburgh before heading back to Norway for refuelling.

But the town also manufactured munitions and food, while CPT engineering works made bayonets and Spitfire engine parts.

During 18 months of the war, Fraserburgh was at the frontline when it came to aerial bombardment.

War Office reports held by the National Archives show that at one point in the war, per head of population, more people were killed in Fraserburgh than London.

This earned the town the morbid nickname ‘Little London’.

Newspaper reports censored to protect morale

But despite dozens of casualties and thousands of injuries, the Broch bombings were kept fairly quiet.

Press censorship during the war forbid newspapers from reporting on specific events that could give Nazis a strategic advantage.

Strict guidelines were issued about what not to print and broadcast.

Information about exact locations of troops, or even weather reports, could give away military details if the papers got into the wrong hands.

Some articles even had to be submitted to the Press and Censorship Bureau to be physically redacted before they could be published.

So when bombing raids took place in the north-east, while it could not be denied lives had been lost, the P&J and EE were banned from giving exact locations.

Instead, ambiguous articles would say a “north-east town” had been raided – which could be anywhere between Moray and Montrose.

It was felt the truth would be bad for morale.

Department store inferno put Fraserburgh in enemy’s sights

But there was no denying the horrors experienced in Fraserburgh on November 5 1940.

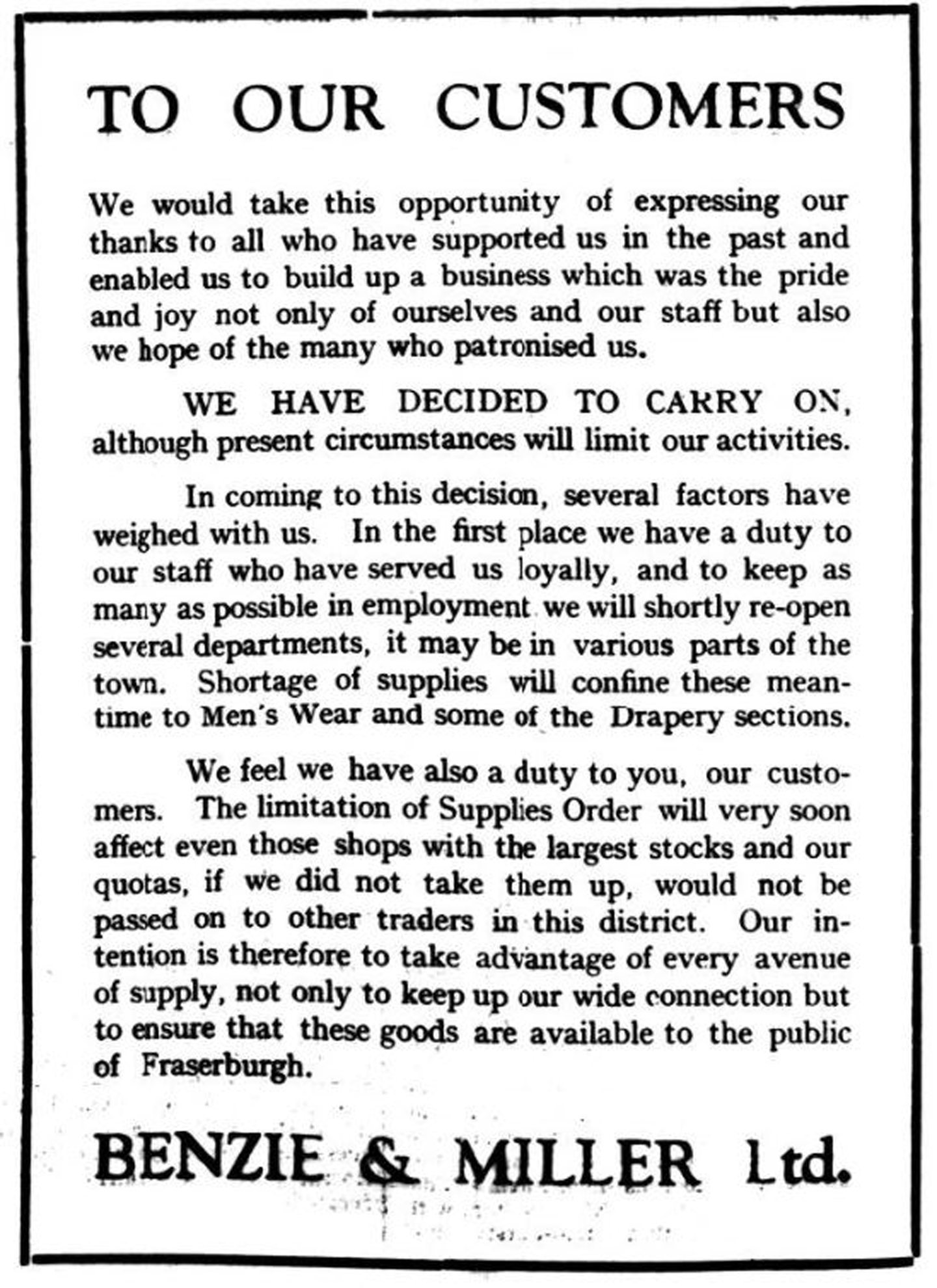

The night of terror started when department store Benzie and Miller on the town’s Mid Street caught fire around 7pm.

The catastrophic blaze broke out accidentally in the retailer’s workshop where a large amount of flammable material was stored.

The P&J reported: “The building became an easy prey to the flames, which shot skywards in a most awe-inspiring manner, and a light breeze carried embers and a shower of sparks all over the district.”

The spectacle of the shop fire drew large crowds as firefighters fought to save the Picture House on the other side of the street.

It was estimated that £50,000 of damage had been caused, but the true cost was still to come.

In the midst of the wartime blackout where no light was permitted after dark, the raging inferno didn’t go unnoticed by enemy pilots.

Nazis dropped bombs during Fraserburgh blitz with ‘calculated brutality’

The din of the roaring fire and the pumps meant nobody heard the aircraft soaring stealthily overhead.

It was only when the first explosive dropped just after 9pm that people realised they were in the midst of a raid.

The P&J reported: “Guided to the town by a big fire, the Nazi raiders, with calculated brutality, tried to drop bombs on the crowd watching the blaze.”

With a whistle and a flash the bomb exploded, and the mob of people ran to safety.

Bombs rained down on town centre buildings, striking homes and shops, showering bystanders in masonry.

One man was killed when a boulder landed on top of him.

And the Commercial Bar – known locally as O’Haras after its proprietor Peter O’Hara – suffered a direct hit.

The popular pub at the top of Kirk Brae was packed with punters watching a darts match.

It was destroyed and two neighbouring buildings caught fire, although the church directly opposite miraculously escaped unscathed.

But the same couldn’t be said for the Commercial’s customers.

At least 23 people were killed and 14 were injured, while a women and children were killed in the buildings next door.

People standing outside the bar were blown off their feet, but survived.

A fire also broke out in the shell of the bombed-out pub, while firefighters were still trying to bring the department store blaze under control.

‘Terrific explosion and crashing masonry’

Despite being unable to print where the bombing took place, the papers did print first-hand accounts from survivors.

One man who escaped with his life told the P&J: “A few minutes before the bombs fell, I was standing at the corner where the public house is situated.

“I was just going across the street when I heard the whistle of a bomb. I threw myself flat and miraculously escaped.

“A young lad near me, who did not throw himself down, was considerably injured.

“I don’t know how I escaped, as I was not more than 10 yards from the building which was hit.”

Another woman, with her bloodied head swathed in bandages, said her family owed their lives to taking shelter downstairs in their house.

She explained: “I don’t know yet how we did escape.

“Every one of us – and there was a considerable number, including some children – came out absolutely unscathed.

“When the terrific explosion and the tearing and crashing of masonry and woodwork had subsided we were able to clamber over the debris of broken woodwork to the street in safety.”

Fraserburgh suffered colossal loss of life in blitz

A witness described how police men, volunteers, firemen and air raid precaution wardens began pulling away at the wreckage of the pub.

“They soon uncovered a number of bodies”, he added.

While civilians and fire crews desperately tried to save lives, the German bombers returned unleashing another three bombs.

Luckily for the traumatised town, this time they landed on open ground.

The darkness of the blackout hampered rescue efforts.

By 9am the following day in the cold light of day, several more bodies were found in the still-smouldering pub ruins.

Some were only identified by their personal belongings.

While it was feared others were still trapped alive.

Between the pub and neighbouring houses there was a colossal loss of life.

Dozens of widows were made that night.

The Evening Express reported that 31 people perished that fateful night, but because official details weren’t made public, the number varies.

Local accounts suggest 34 people died, while the War Office documents say 23 were killed.

But the casualties would undoubtedly have been greater had the first pilot not already dropped some of his bombs.

Fraserburgh on the front line

It wasn’t the last time Fraserburgh and the north-east corner would come under enemy fire.

When enemy crews were shedding their loads before returning to Norway for refuelling, sometimes it was just pot luck where the bombs landed.

On one occasion as a Luftwaffe pilot circled Buchan dropping bombs, he struck a distillery bond near Boyndie.

The P&J reported that it meant “free whisky for beast as well as man”, because cattle grazing on the pasture soaked by whisky fell under the influence of alcohol.

They were seen “stytterin'” around the field, but luckily there were no human casualties.

But another serious attack took place the following year on April 5 1941 when Maconochie’s food factory received a direct hit.

Five people were killed and 112 were injured.

Just 12 days later a new housing scheme on Castle Street was attacked and another seven civilians died, with many more hurt.

In 1943, an air raid shelter was blown from its base near the School Street housing, killing one person and injuring 27.

It’s easy to see why war office files said: “For a long time, Scotland’s front-line towns were Aberdeen, Peterhead and Fraserburgh.”

But nobody in the Broch could have imagined that the abominable scenes from the front line of war in Europe would come crashing down into the streets where they grew up, shopped and socialised.

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

Conversation