“Have you ever been kicked in the neck by a horse?”

I looked at the doctor, a bear of a Czech man in a white coat, who had just unceremoniously threaded a camera up one of my nostrils and down my throat.

“Not that I can remember…?”

It was only when on I was on the tram home, I realised I was wearing cowboy boots. I wanted to laugh but I couldn’t breathe. Diagnosis: cowboy, apparently.

Two years earlier, I was newly pregnant and we were calling our little boy “peanut” to reflect his size. I started having trouble breathing.

I recorded a BBC Radio 4 documentary called Class Talk. On the internet, you can still hear me struggling, my sentences trailing off as my lungs deflated like balloons.

It got worse as my baby grew – I abandoned a radio interview in Spain midway through. I spent a lot of time lying on the sofa, listlessly. Self-diagnosis: pregnancy.

Busy thinking of everything and everyone but myself

Once my son was born and I didn’t have the World’s Biggest Baby pushing everything around inside me, I thought I’d get better, but I struggled more. Still, I reasoned, I was carrying baby and night feed chocolate weight. Self-diagnosis: fat.

In spring, I found it difficult to shower or dress without sitting down afterwards to rest. But, I was constantly catching my toddler’s colds and was painfully sleep-deprived. Self-diagnosis: motherhood.

I know I should have had it checked out. But, like most working mums, I was busy and thinking of everything and everyone but myself.

I was mothering, trying to be a good partner and friend. I was working. I was taking our son to finally meet his family overseas. Plus, there were endless mountains of laundry and deadlines, and when will I ever have time for a haircut? Each day, I had less and less oxygen to do these things, let alone make a doctor’s appointment.

By the time I saw the specialist at one of the largest hospitals in Prague, I could barely walk a few steps without gasping

My husband insisted, in the end. The GP sent me to an allergist – a warm, energetic woman with a shock of blue hair – who sat at her desk quietly, urging me to inhale, exhale. She looked worried and sent me straight upstairs to the ear, nose and throat specialist. Diagnosis: highly alarming and definitely not asthma.

Put your health first

By the time I saw the specialist at one of the largest hospitals in Prague, I could barely walk a few steps without gasping and could only get out of bed for 90 sedentary minutes at a time. He also used the nostril camera of torture – “Stick your head forward, like this, like a turtle coming from its shell.”

He showed me pictures – my trachea, thick with scar tissue so only a tiny hole smaller than the top of a pencil was visible. I had been breathing (or not) through a six-millimetre diameter hole.

Then, he booked me in for emergency surgery: “You understand if you get a respiratory infection right now it could kill you.” Diagnosis: idiopathic subglottic stenosis.

Idiopathic subglottic stenosis is extremely rare; only one in 400,000 have it. As the name suggests, there’s no known reason why I have it. As my aunties said about both great and terrible luck, my “bingo numbers came up”.

I’ll have intermittent surgery for the rest of my life to keep my airway open

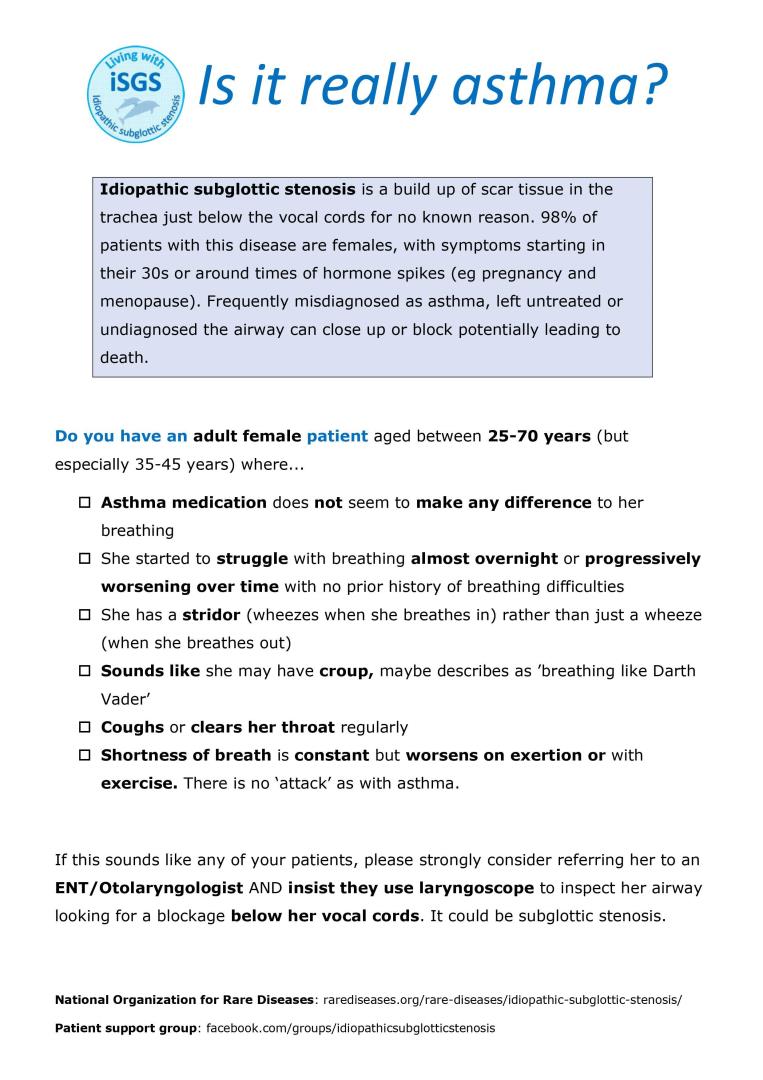

I’ve learned 98% of those diagnosed are women between 25 and 70 years old (but especially between 35 and 45). It’s frequently misdiagnosed as asthma.

A “living with idiopathic subglottic stenosis” support group suggests, particularly if you fall into the above category with breathing issues that don’t improve, to ask for referral to an “ENT or otolaryngologist for a laryngoscope to inspect below the vocal cords”.

Self-diagnosis: don’t prioritise everything but your health. Self-care doesn’t just mean a Cadbury Flake and a scented candle.

I’ve been given second chance to live fully

My surgery was a huge success. Two weeks later, I am back to singing, dancing and spinning my little boy in the kitchen to Whitney Houston. But there is no cure.

The scar tissue will grow back. Next time, they’ll remove the affected trachea and reconstruct it, likely with a piece of my rib. I’ll have intermittent surgery for the rest of my life to keep my airway open.

I am so fortunate. My husband looked after my health even when I didn’t. The blue-haired doctor sat quietly and simply listened to me breathe.

I’m in Prague, where I can access excellent public healthcare with an excellent surgeon. Kind nurses, cleaners and porters in the hospital patiently tried to understand my terrible Czech, patting my arm tenderly. I’ve been given second chance to live fully, joyfully and gratefully every single day.

Diagnosis: lucky.

Kerry Hudson is an Aberdeen-born, award-winning writer of novels, memoirs and screenplays. She lives in Prague with her husband, toddler and an angry black cat