Columnists are often accused of being deliberately controversial in a base attempt to draw attention to themselves.

There are a number of high-profile writers who have built careers along these contrarian lines – the kind who, in recent days, will have churned out a thousand lachrymose words arguing that “all poor Novak wants to do is play tennis”, or that “Prince Andrew is a credit to the Queen”. Whatever the general public view is on any given subject, they adopt the opposite position and then luxuriate in the subsequent online outrage.

I’ve never gone in for this approach – partly because it’s juvenile and unserious, partly because taking Katie Hopkins as a role model seems somewhat bad for the soul. Investing in what’s been called the “attention economy” should hold precisely zero appeal for grown-ups.

And, so, today I want to write… in defence of politicians. Hold up now, come back… hear me out.

You’ll find integrity outside the craven, unprincipled inner circle

It may be the case that an article by a journalist (one of the least trusted professions) in praise of politicians (another one) is fatally flawed from the outset. It’s also true that the behaviour of some employed in both of these occupations leaves a lot to be desired; that the lowly reputation has at least some justification.

But the danger – and in a sense it has never been higher – is that the best are unfairly tarnished by association with the worst. To be clear, I have no intention of excusing Boris Johnson, the most unfit individual in living memory – and perhaps even beyond that – to hold the office of prime minister.

His latest right-wing spasm in an attempt to shore up his deflating premiership is as predictable as it is lamentable. It’s hard, too, to defend some of those he has appointed to his cabinet, whose only qualification seems to be a fealty to the boss that would withstand his triple unmasking as a Chinese spy, Bible John and a dementor.

Outside this craven, unprincipled circle, however, are many men and women of the highest integrity and ability. They entered politics in an attempt to change the world for the better, are committed to their constituencies, engaged passionately in matters of national and international debate, and sacrifice huge amounts of their personal and family time for the sake of society. However it currently feels, politics is not an ignoble pursuit, even if a minority of those who enter it have the morals of an alley cat.

Few politicians are in it for themselves

In my twin jobs as a political commentator and running a think tank, I spend a large amount of time talking to ministers, MPs and MSPs. I can count on one hand the number who I would classify as “in it for themselves”. These types exist, are usually quite easy to spot, and quite often climb the greasy pole precisely because they devote so much energy to doing so. But they are genuinely few and far between.

There is a tension in politics between its showbiz side and the unsexy graft that is the reality of the day job

Our chats are more likely to be about the underperformance of Scotland’s schools, or the failings of the NHS, or what might be done to return the economy to health. I learn a lot from these conversations – with politicians of all parties – and am regularly impressed by the depth of knowledge and expertise on display. I’m rarely given reason to question their motives.

There is brilliance and passion on every party bench at Holyrood. I think of Kate Forbes, the SNP’s young economy secretary, who could doubtless be earning a great deal more working in the private sector but who has a geeky obsession with policy that will fit out the Scottish economy for this fast-changing century. I think, too, of Michael Marra, Labour’s relatively new education spokesman, who has taken to his brief with energy and elan.

The Tories’ Donald Cameron has a big brain, humility, and the perfect temperament for government – though, given his choice of party, this is sadly unlikely to be tested. Andy Wightman, until recently a Green MSP, was respected across the chamber for his depth of knowledge on localism and land ownership, and for his open, curious mind – though, when it turned out to be too open and curious for the bigoted obsessives in his party, he was forced out.

These are only a selection – I could have chosen others.

There is a tension in politics between its showbiz side and the unsexy graft that is the reality of the day job. A lot has been written about Boris Johnson’s “charisma” and Keir Starmer’s apparent lack of it, but which of them would you trust with your bank card or your pension, to babysit your kids, or to check in on an elderly relative?

This, in a microcosm, is what the job of politician really entails. In these tumultuous, troubling times, we do well to remember that.

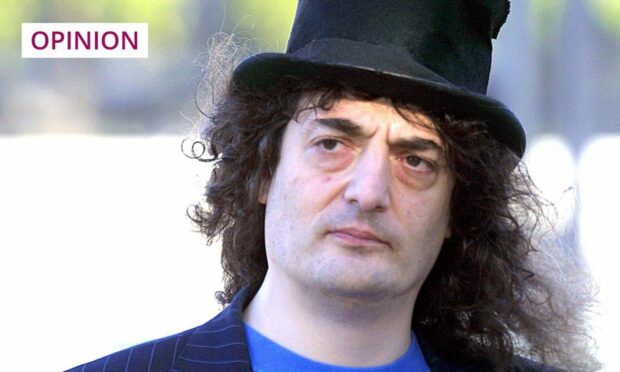

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank, Reform Scotland