I wonder how many watershed moments there are to be.

Every time a powerful man is exposed as a sexual predator, we tell ourselves things are going to change. We praise the bravery of those who spoke up, and insist their courage will have lasting, powerful consequences.

And then nothing changes, at all, does it?

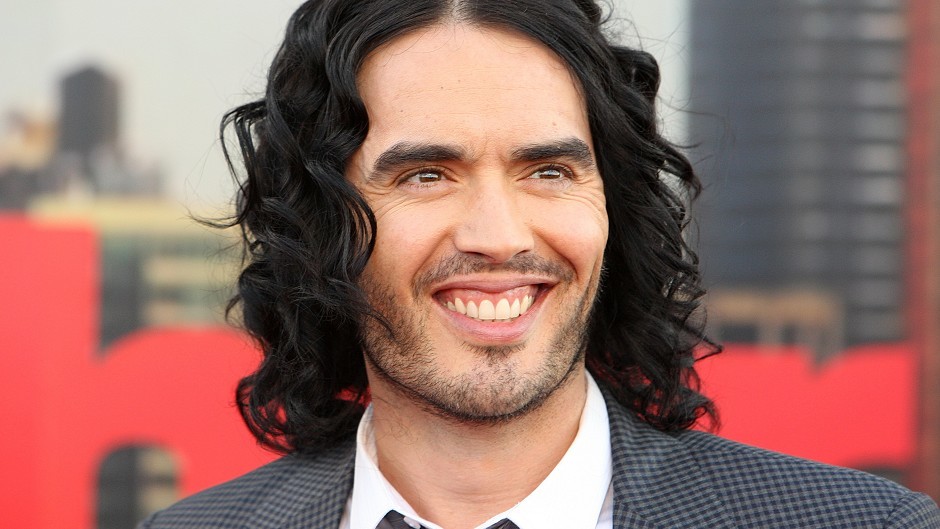

Much of the reaction to the distressing testimonies of a number of women about their experiences with Russell Brand confirms this.

Of course, there’s been righteous condemnation but there has also – particularly across social media – been a disturbing backlash against those who spoke up.

Conspiracists – and good, old-fashioned misogynists – ask why, if Brand’s behaviour was so abhorrent, these women didn’t ago public sooner? Some insist that – in the absence of a criminal trial leading to a guilty verdict – there is simply nothing to see, here. Many buy into the fanciful idea that Brand is the victim of a sinister plot designed to silence him because, via his YouTube broadcasts, he’s uncovering “truths” that have “the establishment” running scared.

It’s little wonder that so many women prefer not to speak up about their experience of coercive behaviour, sexual assault, and rape, is it? After all, if she wasn’t asking for it, she’s looking for something in return for lying.

It is all so impossibly bleak.

Actually, it wasn’t all ‘just a laugh’

As an 18-year-old entering in the adult world of employment in 1988, I was entirely complacent about the issue of equality. Raised by a mother who worked full time and with a female boss, I reckoned the time when women were discriminated against had passed. I foolishly thought I was living through the early days of a new, enlightened era.

It didn’t take me long to recognise my own stupidity.

Sexism hadn’t been eradicated. It had been painted over with a thick layer of “irony”.

The rise throughout the 1990s of the so-called lads mag saw traditional sexist behaviour rebranded as good, naughty fun. If a male actor appeared in their pages, he’d be styled like James Bond and treated with respect. If a female actor wished to give an interview, the condition was that she’d pose for photos in her underwear.

Yes, you may argue that the countless women who appeared on the pages of Loaded, FHM, Nuts and Zoo knew what they were doing and that their participation in explicit photo shoots was consensual, and you may well be right. But these were women navigating a culture where the expectation was that they’d play along, and their failure to do so might harm their careers.

It’s not for me to deny the agency of the women who became icons of the lads mag era, but I know that, often, they were under pressure from male agents and managers who insisted that stripping off for Loaded and then answering intrusive questions about their sex lives was part and parcel of the business called show.

When Russell Brand became a star in the early 2000s, his “outrageous” and “edgy” schtick was enabled and encouraged by a popular culture which told young men – and young women – that it was all just a laugh.

We need honest reflection and action

If we look back to the time of the lads mag and recognise a problem, we must accept that things have got worse.

Teenagers now have access through their phones and laptops to an endless stream of degrading pornography. If lads mags encouraged the acceptance of sexism as fun, this stuff encourages the belief that women are positively enthusiastic about sexual violence.

I’m always wary of men who declare themselves feminists. I believe them in the same way I believe people who make a point of insisting they aren’t racist.

These performative statements of solidarity might make the man in question feel like one of the good guys, but I think quiet – and honest – reflection might be of more use.

One needn’t be a predator to recognise the worst aspects of masculine nature. We men know what we’re capable of

If a man says he can’t understand how some others behave the way they do, then he’s lying to himself or stupid.

One needn’t be a predator to recognise the worst aspects of masculine nature. We men know what we’re capable of, even if we’re repulsed by the likes of Russell Brand.

There will be many more watershed moments to come, but I’m not sure what difference they’ll make.

That’s not to say there aren’t things men could do to try to improve matters. We could start by believing victims, and then we could talk to our sons – and daughters – about the damaging impact of violent pornography.

Euan McColm is a regular columnist for various Scottish newspapers