It was delightful to see snow falling in our garden just before Christmas.

Clinging on for dear life, but sad to say it didn’t last until the big day (pre-Storm Gerrit, of course).

I thought about the haves and have-nots at Christmas. Life and death, as people passed on and newborns arrived; more poignant with the new year.

My phone rang as I admired the Christmas-card scene from our kitchen in Aberdeen.

A hospital registrar in Birmingham was calling about someone dear to us who was also clinging on – my wife’s mother. At 91 with dementia and chronic heart failure, along with multiple associated medical problems, the end seemed closer.

I’ve written extensively about her trials and tribulations south of the border because it strikes a chord with others in Scotland with relatives scattered afar.

Her waking hours are torture; the only respite is sleep. Dementia is like an alien imposter which hijacked her mind.

So pitiful that some who know her have uttered a familiar taboo: “You wouldn’t let an animal suffer like this.”

In other words, arrange a merciful exit – if it was legal. Easy to say, but how many could really make that decision?

I’m left thinking that the doctors still know best

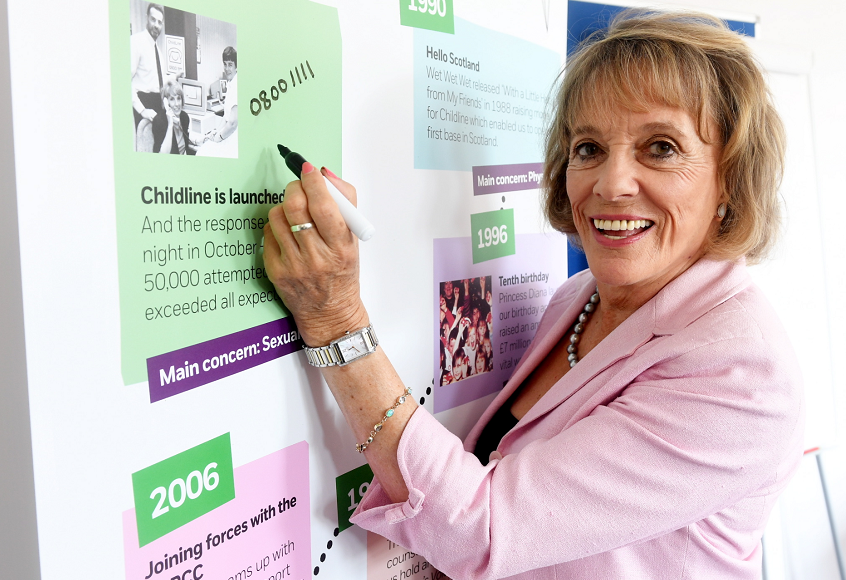

Euthanasia and assisted dying are back in the news following Dame Esther Rantzen’s revelation about plans to end her life prematurely as a result of lung cancer.

My mother-in-law’s doctor explained gently that her situation was so dire, we might be asked in a few days to approve medication being withdrawn, if there was still no sign of it working. She would then make her “as comfortable as possible”.

It began to dawn on me what might happen next. I said that sounded as if nature would be allowed to take its course, as there was no other option left; she agreed.

I suppose it’s another form of assisted dying that’s always been with us – relying on doctors to help make the inevitable more peaceful and bearable under tightly-controlled medical conditions.

But the question is: how much suffering is acceptable before reaching this point?

The fact that my wife and I could have a direct influence on life or death – by giving the go-ahead to this process – brought home the enormity of the issues raised by the Rantzen debate.

Public opinion favours a loosening of legislation by following other models of assisted dying around the world. I think that’s right, but the fine details and practicalities pose huge challenges before reaching that stage.

It raises the spectre of sick people deciding to go early because they feel a burden, or, worse: others making them feel a burden. I’m left thinking that the doctors still know best.

Ironically, this is the bedrock of the Oregon Death with Dignity Act in the US, which has been operating for more than 25 years and was cited recently as an example for the UK to follow.

In Oregon, there is a strict criteria where adults must have six months or less to live, and be in a sound state of mind to make the decision to die legally. They must also take the fatal medication themselves. Crucially, it’s the physicians who oversee and approve the whole process.

Governments must be challenged daily, whatever their colour

We were naturally numb with shock as we stumbled into Christmas. So, we were a little alarmed by a reader who took me to task wrongly for supposedly exploiting mother-in-law’s plight “to take a swipe” at First Minister Humza Yousaf and his health secretary Michael Matheson in a recent column.

The letter said I allegedly gave the impression that she was under Scottish care after omitting to say she lived outside Scotland.

There was something illogical about this. I never said she was in Scotland in the first place.

Ironically, the complainer knew from my previous columns that my mother-in-law was not in Scotland – so, logically, everybody else with an interest would presumably know, too, I reckon.

Therefore, the thought of me trying to create a false impression – after I had placed her whereabouts in the public domain myself over several months – was preposterous.

Just for the record, references to my mother-in-law only dealt with bureaucratic muddles facing her and other patients, and my call for smoother interdepartmental hospital relations. Meaning inside the “monolithic” UK NHS after comparing the scale of reforming it to taking on the military system – no “swipe” at the SNP.

My only “swipe” at Yousaf and Matheson was clearly confined to ghastly ambulance queues at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, and their personal distractions over grandiose showboating or embarrassing cover-ups. I’m happy to repeat that, too.

I stand accused of being “anti-SNP and doing Scotland down”. But governments must be challenged daily, whatever their colour – especially with a track record like this one. With a fog of cover-up, lack of transparency, incompetence and wasting public cash swirling around it.

Far from doing the country down, challenging the government actually makes Scotland better.

David Knight is the long-serving former deputy editor of The Press and Journal

Conversation